- O black and unknown bards of long ago,

- How came your lips to touch the sacred fire?

- How, in your darkness, did you come to know

- The power and beauty of the minstrel's lyre?

- — James Weldon Johnson, "O Black and Unknown Bards"

Huddie Ledbetter didn't like to be called "Lead Belly." One of his relatives told me. Florida Combs was his second cousin, and spoke with the authority of great age and seriousness.

She said he tolerated the nickname because he understood it was a show-business conceit, that it sold tickets and drew interest. He tolerated a lot in the name of commerce, allowing himself to be presented as a dangerous and untamed criminal to eager up the blood of the Bryn Mawr girls come to watch him sing and play — some kind of minstrel Mighty Kong.

So I try not to call him Lead Belly, though sometimes I slip up, for the same reasons of expediency that caused him to grudgingly accept the nickname. ("Don't get too close, girls — a gutload of shotgun pellets couldn't kill this beast.")

There is a Little Golden Books fairy story about the "friendship" between the convict Huddie Ledbetter and the white man who "saved" him, John A. Lomax. The rough outlines are that Lomax met Ledbetter when he was making field recordings of folk musicians during the Depression. Lomax and his son Alan traveled to Louisiana State Prison at Angola to record prisoners in 1933; Ledbetter was among the inmates he recorded.

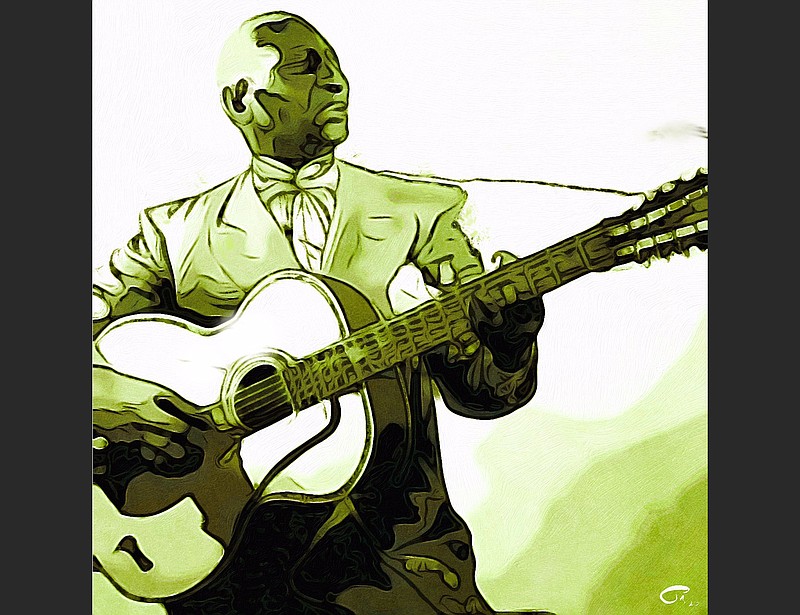

The legend is that Lomax recognized in Ledbetter a singular talent, and arranged to have him sing for Gov. O.K. Allen, who pardoned him on the spot. Lomax and Ledbetter then teamed up to spread the gospel of the King of the 12-String Guitar.

The truth is more prosaic; Lomax did meet and record Ledbetter, and Lomax did deliver a copy of his recording to Allen, who may or may not have listened to it. But the governor did not pardon Ledbetter right away; Ledbetter was released in 1934, when he became eligible for early release. After he was released, he wrote to Lomax, asking him for a job. Lomax agreed to an interview.

Lomax later told the New York Herald Tribune about meeting Ledbetter:

"On Aug. 1, Leadbelly [sic] got his pardon. On Sept. 1, I was sitting in a hotel in Texas when I felt a tap on my shoulder. I looked up and there was Leadbelly with his guitar, his knife and a sugar sack packed with all his earthly belongings. He said, 'Boss, I came here to be your man. I belong to you.'

"I said, 'Well, after all, I don't know you. You're a murderer ... . If someday you decide on some lonely road that you want my money and my car, don't use your knife on me. Just tell me and I'll give them to you. I have a wife and a child back home and they'd miss me.'"

I'm not sure how much we should credit Lomax's statement to the Herald Tribune; his interest at the time of the interview was establishing the burlesque act, which Ledbetter's career was to become. Lomax was hyping a tour of northern colleges he had arranged for the "Sweet Singer of the Swamplands." Ledbetter's substantial criminal history was played up as a drawing card. Lomax called him a "natural" with "no idea of money, law or ethics ... possessed of virtually no self-restraint."

This was what Huddie Ledbetter tolerated.

OUT OF MISSISSIPPI

John Avery Lomax was not a woke person.

He was born in 1867, shortly after the end of the Civil War, in Goodman, Miss. His father, who was then in his 50s, had been conscripted to work as a shoemaker for the Confederate side. The family moved to Texas when Lomax was 2 years old, and Lomax would later write that he developed a passion for folk music by listening to the trail songs sung by Black cowboys. He was still in his teens when he began collecting these songs.

In 1895, after working on his father's farm for years, he enrolled in the University of Texas where his professor Morgan Callaway dismissed the cowboy songs he had collected as "cheap and unworthy."

Lomax burned all his notes and went on to become an English teacher at Texas A&M University, where his scholarly interest in folk music was rekindled. He continued to take graduate courses in the summer at the University of Chicago and at Harvard, where he was awarded a master's degree in English.

By 1931, Lomax was seemingly done with academia; he was a widower working in a Dallas bank. It was his job to call the bank's customers one by one to inform them that their investments were worthless. At 64 years old with two school-age children and in debt himself, he quit the bank and sank into a deep depression. In hope of reviving his father's spirits, his oldest son, John Lomax Jr., encouraged him to restart his research.

In June 1932, Lomax proposed to the Macmillan publishing company his idea for an anthology of American ballads and folk songs, with a special emphasis on the contributions of Black artists. It was accepted. He arranged for the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress to provide him with recording equipment, and he set out on the road that would eventually bring him face to face with Huddie Ledbetter.

A VIOLENT MAN

We should not overlook that fact that Ledbetter was a violent man.

But just as John Lomax was a product of his time and circumstances, maybe Ledbetter was not exceptionally violent given his background. The jukes and blind tigers he played in were rough joints; there were lots of knives and razors and guns about. And these days we might say he had a talent for self-sabotage, for wrecking whatever beauty wandered into his orbit.

Born near Mooringsport, La., in 1888 (or 1885, depending on the source), Ledbetter was something of a musical prodigy, mastering the rudiments of the keyboard by the time he was 8 by playing a single-key accordion called a windjammer.

Later he played piano and organ and learned guitar — six-string at first, the 12-string came later — from men like Jim Fagin and Bud Coleman, who played in the brothels and on the streets of Shreveport's St. Paul's Bottoms. By the time he was 16, Ledbetter occasionally joined them, though he mostly played rural house dances and breakdowns (often with his cousin Edmond "Son" Ledbetter, Florida Combs' father).

Along with his battered guitar, they say, he carried a Colt revolver. There is a lot of apocrypha — the story about him being shotgunned in the gut by a Caddo Parish sheriff's deputy is likely false — but we know some things to be true.

Ledbetter found himself in Dallas, in the district they call Deep Ellum. There he heard the rolling barrel-house styles of piano men who used heavy-walking bass figures he'd later transpose to his down-tuned guitar to create a new vernacular for the instrument. But the most important thing Ledbetter learned had nothing to do with technique and everything to do with giving voice to that inexpressible hurt called blues. His primary teacher was a fat, bland-looking blind man from about 80 miles south of Dallas, 10 years his junior, with an eerie, neck-prickling talent: Lemon Jefferson.

It may be nothing more than a chauvinism of the sighted, but it has often been implied that the blind are somehow gifted with an especially sensitive nature. While blind musicians — especially if they are Black men — are often viewed, rather romantically and patronizingly, as savants, the overriding and overlooked reasons blind instrumentalists have played such a large part in shaping the blues are economic. Music is one occupational avenue the blind can pursue on almost equal footing. A blind boy was unable to work in the fields, and a poor blind boy was unable to lay up and be taken care of by his family.

When Ledbetter met Jefferson, probably around 1912 (Ledbetter once told an interviewer he was "runnin' with" Jefferson for about 18 years, but the claim is dubious; it was more like five) the blind man was just another struggling street musician, too independent to allow himself to be led around, too mean to be partners with anyone for very long.

But for a time before Ledbetter was sent away for manslaughter, the two played together in Dallas and Shreveport, in little town train stations, in dozens of anonymous and long-disappeared honky-tonks in Corsicana and Waxahatchie.

This was a crucial period of pollination. At the time, Ledbetter operated as a songster, a human jukebox specializing in reels and ballads, the most popular music of his day. While Ledbetter was the older partner, and probably more mentor than pupil (though in later years he'd claim it was the other way around), Jefferson scraped up against him with the blues and changed him.

The faceless crowds who sat and drank or danced and sweated through the sets the men played may have guessed they were witnessing something rare. Jefferson's hands scampered over the fret board, echoing the high keen of his voice, in what must have been a marked contrast with Ledbetter's (then) warm tenor and accomplished playing.

FIRST PRISON BID

That partnership ended in 1917. Three musicians were traveling together near New Boston, Texas. They were the sort of rough young men to whom bad things happen. Maybe the one who called himself Alex Griffin said something about a woman to the one who called himself Will Stafford. Maybe this made Stafford angry, and maybe the one who called himself Walter Boyd — a guitar player of heavy build whose neck was ringed by a smile-shaped scar — intervened.

Combs' version is Stafford went for his pistol and Boyd (Ledbetter, who had adopted the alias after walking away from a chain gang) shot him through the head.

Court records confirm that on Dec. 13, 1917, Boyd was charged with murder. He was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 35 years in prison.

It seemed likely he'd die behind bars. In 1918, the Great War and the Spanish flu combined to depress the average life expectancy for an American male that year to 36.6 years. (American women, who were much less likely to die in the war, could expect to live to 42.2 years. In 1919, male and female average life expectancies jumped, respectively, to 53.5 and 56 years.)

But in 1924, Ledbetter sang his way out of prison. Maybe.

What we know is that while at Shaw State Prison Farm, Ledbetter performed in a convicts show. Texas Gov. Pat Neff was in the audience; on a subsequent visit to the prison, Neff asked Ledbetter to sing for him again.

The legend is Ledbetter performed a song that included the line, "If I had you Governor Neff like you got me/I'd a-wake up in the mornin', I would set you free." (Ledbetter would later record several variations of this liberation song, under the titles "Sweet Mary," "Governor Pat Neff" and "Please Pardon Me." And a version of the line appears in some renditions of the traditional song "The Midnight Special." Considering the storytelling tendencies of both Ledbetter and John Lomax, it's probably fair to take any claims that Ledbetter made such a direct appeal with a grain of salt.)

Maybe this charmed Neff, or maybe he'd already made up his mind, but on Jan. 16, 1925 — his last day in office — the governor issued a proclamation that granted "Walter Boyd" and four other inmates full pardons. That this was not done lightly is evidenced by the fact that Neff had campaigned as a reformer, railing against the hundreds of pardons his predecessor "Big Jim" Ferguson had issued while in office. These five last-minute pardons were the only ones Neff issued during his term in office.

Ledbetter moved back near his family home in Louisiana. For five years he lived quietly. He joined the church and drifted back into playing.

His repertoire had changed — darker, bluesier. If Jefferson gave him a voice for the blues, the prison farm gave him the heart for them.

Then on Feb. 28, 1930, he was arrested for assault to commit murder. Within a few weeks, he was back in prison.

A SHORT PARTNERSHIP

The partnership between Ledbetter and John Lomax lasted five or six months. Lomax hired him as his personal assistant and driver, and Ledbetter's encyclopedic knowledge of folk music was certainly an asset in the field recording sessions.

Then Lomax designed an East Coast college lecture tour where Ledbetter would assist him by performing examples of the primitive art. In January 1935, Lead Belly signed a management contract with Lomax. This contract stipulated the split of performance fees, royalties and the assignment of copyrights.

So Lomax became a co-writer of "Goodnight, Irene." (Which, to be fair, Ledbetter didn't really write either; he admitted hearing his Uncle Terill play the song as early as 1908. But we'll save the copyright debate for another column.)

The partnership fell apart quickly; Ledbetter was frustrated by his working relationship with Lomax and the patronizing monthly allowance he received. Lomax would tell audiences how he couldn't give Ledbetter money directly for fear that he'd spend it all on whiskey. So he'd give it to the singer's wife, Martha, to hold.

Ledbetter tolerated that. For a while. Then he retained legal counsel and threatened to sue.

It is unlikely the suit was ever filed. Instead, a settlement was reached; it included one full lump-sum payment and a split of potential royalties from Lomax' book "Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly." Lomax also negotiated a recording contract for Lead Belly with the American Recording Company. While Ledbetter recorded more than 40 songs for ARC, the label released only a couple of sides.

As ugly and exploitative as this might sound today, we should remember John Lomax and Ledbetter were co-conspirators. Lead Belly became a celebrity, a minor don of Greenwich Village as he drifted into a supportive circle of mostly white folk performers including Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Cisco Houston. And, after a spell of managing his own career, Ledbetter contacted Lomax again, hoping to secure a new management deal.

We should also not conflate John Lomax with his son Alan, who was far more progressive when it came to race relations. In 1939, when Ledbetter once again found himself in legal trouble — he was arrested for assault with murderous intent after knifing a man in a bar brawl in Manhattan — it was 24-year-old Alan who arranged for bail, raised money for Ledbetter's legal fees and financially assisted Ledbetter's family during the months Ledbetter spent on Riker's Island.

A CAREER REBORN

Alan oversaw Ledbetter's 1940 RCA-Victor album "The Midnight Special and Other Southern Prison Songs," secured a long-term recording contract with RCA Victor and arranged for Ledbetter to promote himself through radio appearances and live performances. He would oversee the re-recording of Ledbetter's repertoire for the Library of Congress and document the stories behind those songs.

He introduced Ledbetter to Mose Asch, for whom Ledbetter would record three albums. That would lead to a deal with Capitol Records and an eventual tour of France. In 1949, a few months before he died of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease), Ledbetter performed a concert at the University of Texas, honoring the memory of John Lomax, who had died the previous year.

To modern ears accustomed to airbrushed tones, Lead Belly can seem harsh and raw. There is a nervous, piercing quality to his voice when it climbs; the limits of the equipment of the day cloak the depths of his 12-string guitar. The recordings have gotten better as our technology increases; we hear him better now than we did in the '70s, but we don't know what we've lost.

Yet, though they are crumbling and dwindling in majesty, we still are awed by pyramids.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com