I started watching "Clark," a six-part Swedish true crime series about the life and times of Clark Olofsson, who is something of a folk hero in Scandinavia, on Netflix last week. The show originally premiered in May; it kept popping up as a suggested watch in my feed.

I generally ignore what the algorithm suggests, partly out of vanity, but mostly because I've got plenty of stuff to watch.

But we fired it up the other night. It's fast-paced and clever, sharply edited with lots of black-and-white archival (and mock-archival) footage stitched in. The cinematography so far has been in the upper echelon of television projects; series from northern Europe always seem so crisp and cleverly shot.

Director Jonas Akerlund — best known for directing Madonna's "Ray of Light" video — has a maximalist sensibility; he crams in a lot about a character who certainly is a lot.

Over an almost 60-year career, Olofsson (Bill Skarsgard, Stellan's youngest son and Alexander's little brother), first glamorized as a celebrity gangster in the '60s, has been convicted of attempted murder, assault, robbery and drug dealing. He's particularly well known for robbing banks.

In 1973, a cellmate and friend of Olofsson's named Janne Olsson was granted a furlough from prison. While on this furlough, Olsson walked into a Stockholm bank with a submachine gun, fired several rounds into the ceiling and announced, "The party has just begun!"

Police officers, responding to a silent alarm tripped by one of the bank employees, arrived before Olsson was able to escape. He shot and wounded one of them, then ordered the other to sit in a chair and "sing something."

The officer chose to sing "Lonesome Cowboy," a song recorded by Elvis Presley, as Olsson ushered four bank employees into a vault. He told police he'd release them in exchange for three million Swedish kronor (roughly $376,000), two guns, bulletproof vests, helmets, and a Ford Mustang. Oh, and he wanted his friend Olofsson brought to the bank.

Surprisingly, the Swedish government agreed to these terms. They brought Olofsson to the bank, along with the money, the gear and a blue Mustang with a full tank. They only insisted that Olsson and Olofsson leave the hostages behind when they left.

This was a sticking point. The bank robbers wanted to take the hostages with them to ensure safe passage. At one point, Olsson was on the phone with Swedish Prime Minister Olaf Palme. To show he was serious, Olsson threatened the life of one of the hostages. As she screamed, he hung up on Palme.

Thus began a several-day siege, covered on live television and highlighted by a call that same hostage made to Palme, not to plead for him to take immediate action to protect the hostages but to scold him for his attitude. She was disappointed in the way he'd spoken to Olsson. To make up for it, he should let them all walk away free.

Finally, after six days, police mounted a tear gas attack, pumping the gas into the vault through a small hole in the ceiling. Olsson and Olofsson surrendered almost immediately, but when police called for the hostages to come out first, they insisted the would-be robbers leave first; they wanted to make sure the police couldn't shoot them in the vault. As their captors were led away in handcuffs, the hostages told everyone who would listen how kind and helpful their robbers have been.

This mysterious empathy was originally described by Swedish criminologist and psychiatrist Nils Bejerot, who called it "Norrmalmstorgssyndromet," after Norrmalmstorg, the area of Stockholm where the bank Olsson tried to rob was located.

STOCKHOLM SYNDROME

It soon became known to the rest of the world as Stockholm syndrome — a psychological phenomenon where a person who has been taken hostage or otherwise victimized by another person develops warm feelings toward their abuser, to the extent that they may seek to defend and protect them.

Upon reflection, the syndrome may not be quite as mysterious. We might understand it as a coping mechanism or survival strategy; one of the hostages admitted she strategically established a rapport with the robber.

In this particular case it's important to note that the hostages inside the bank didn't completely trust the police to prioritize their safety over thwarting the robbery. Olofsson argued in court that he never aligned himself with Olsson, that he was playing a role and working with police to keep the hostages safe. They may have sensed he was looking out for them because he was, to some extent, looking out for them.

While Olofsson was convicted in district court of having abetted Olsson, on appeal a higher court accepted his argument that he had the silent consent of the police. (At one point in the siege, Olofsson slightly wounded an officer; he said he was doing so to maintain his cover.) He was sent back to prison to finish his term, but didn't incur any further time for his involvement in the siege.

Olsson received a 10-year sentence. He blamed the hostages.

"They did everything I told them to," he told a BBC interviewer. "If they hadn't, I might not be here [in prison] now. Why didn't any of them attack me? They made it hard to kill. They made us go on living together day after day, like goats, in that filth. There was nothing to do but get to know each other."

I haven't watched the "Clark" episode that deals with this bank robbery yet — it's an important chapter in Olofsson's life but not the only important chapter — but I did see the 2018 Ethan Hawke film "Stockholm," which was loosely based on the incident. (Hawke plays a character based on Olsson, while Mark Strong plays the Olofsson character, and Noomi Rapace is the hostage who reproaches Olaf Palme.)

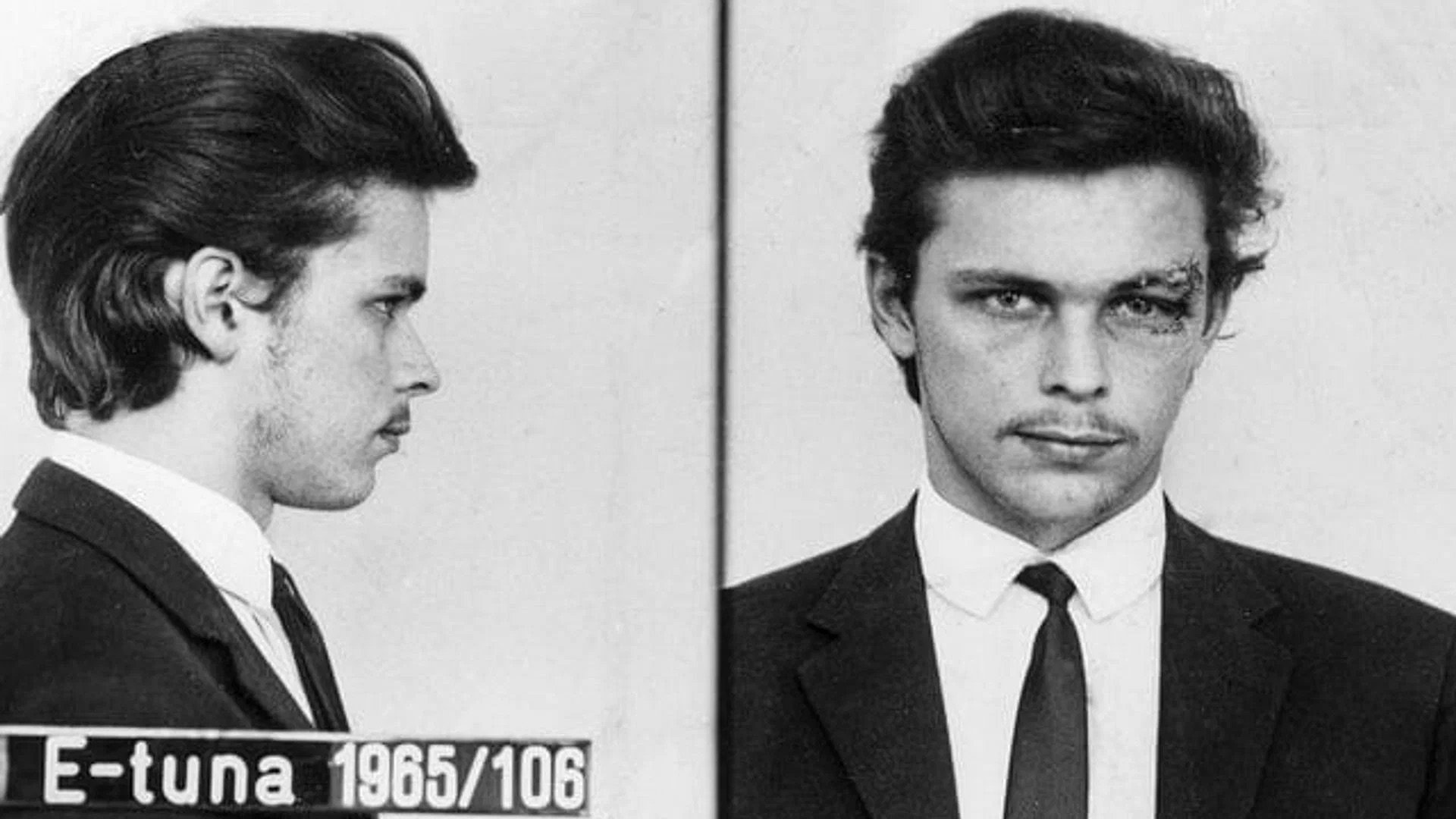

The real Clark Olofsson appears in a mugshot in 1965. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette)

The real Clark Olofsson appears in a mugshot in 1965. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette)

TV — OUR EVERYTHING

Most of us have developed a sort of Stockholm syndrome-style relationship with TV. It has been around our whole lives as babysitter, companion and captor. We tell ourselves we can always turn it off and walk away, but few of us manage that trick.

Someone asked me about television and why I don't write more about it. The answer is that television is an oceanic subject, like Scotch whiskey and football. There are people who presumably know about it; those people devote their lives to their subject. They spend hours a day thinking about Scotch or football. And usually they will be the first ones to tell you they don't know all that much about their field of study, that they are humbled by what they don't know.

That is television. I watch maybe an hour or two a day. There are many famous TV shows I have never seen. I've never watched a reality TV show. With the exception of a few weeks after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, I haven't watched any television news programs (though I catch clips of commentary on YouTube after someone has alerted me to them).

Most of what I watch is programming that, for better or worse, might be described as "prestige television." I watch a lot of HBO series — "The Sopranos," "The Wire," and especially David Milch's "Deadwood." Later this month I'll begin leading a class on the first season of Mike White's series "The White Lotus."

I'm not snobbish — one of my favorite series is the offhandedly bawdy/silly Canadian series "Letterkenny," and I loved its riskier and less refined spin-off "Shoresy." If you ask about my favorite show from last year, I would probably cite the Northern Ireland sitcom "Derry Girls," especially the poignant and hope-inspiring third season.

While I can defend those shows — all exceptional television — I often find myself taken in by shows I wouldn't want to defend. "Downton Abbey" and "Jack Ryan" are trash, but I consume them. I'm looking forward to a second season of Amazon Prime's "Reacher." I watch "Whitstable Pearl" on Acorn, and have no idea why other than it tends to work like Ambien. I'm in no position to roll my eyes at anyone's taste in television; lots of people use the tube as a recreation drug.

The dangers of watching low-quality TV are pretty much the same as smoking weed — the biggest problem it might cause is time mismanagement. Obviously all the time you spend watching television is time you don't spend doing something else.

Junk TV exposes you to low-quality ideas and tends to normalize low-quality modes of thinking. There is such a thing as art that is bad for you, and some of the lowest common denominator stuff that finds its way onto TV is horrifying. That's not counting the targeted misinformation spread by opinionated talking heads on the 24-hour "news" programs.

But you can abuse just about anything.

TRAVEL VIA TELEVISION

One of the things I' ve come to love about television in the current age is the availability of international series like "Clark." Sure, you have to read subtitles, but some of us need subtitles to watch something like "Tulsa King" as well.

We're watching Finnish cop drama "Deadwind" — moody and well-acted, with a narrative that's completely over-the-top (I doubt we'd put up with an American show that so consistently strains credulity) but the best part about it is that, into the third season, it seems like we've been to Helsinki. We have learned a little bit about how the Finns live, and how they seem to have hundreds of ways to employ the English word "OK." We understand a little bit about how they relate to Estonians and Germans and British folks.

Since the advent of covid-19, we seem to have gravitated to these northern European series — starting with the Icelandic "Trapped," re-branded "Entrapped" for its third season (now on Netflix; we watched the first two seasons on Amazon Prime). We've watched the Danish series "Borgen," and a lot of Nordic noir shows.

Since covid, television has been our main way of exploring those parts of the world we'd otherwise need a plane ticket to get to. It's become an almost literal means of transport.

I know TV is dangerous, that it doesn't have my interests at heart. I love it anyway.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com