It is never easy to say where anything begins. (You want to argue? Nominate a track as the first rock 'n' roll song ever.) These days Humphrey Bogart begins on television, dryly lisping through a drizzly scrim, or as a face on a T-shirt worn in irony by some glib grad student. John Huston, if he's remembered at all, might be remembered as the heavy in "Chinatown." The past is compacted as it recedes, the 1940s are as remote to most of us as ancient Greece.

We can't help how we come to things. We can only hope we have the grace to recognize them for what they are.

The French coined the term "film noir" in response to a style of Hollywood film that emerged during the '40s. It translates as "black film" and more accurately as "dark movie" and was derived from "roman noir," a term of art used by 19th-century French literary critics to describe the British Gothic novel.

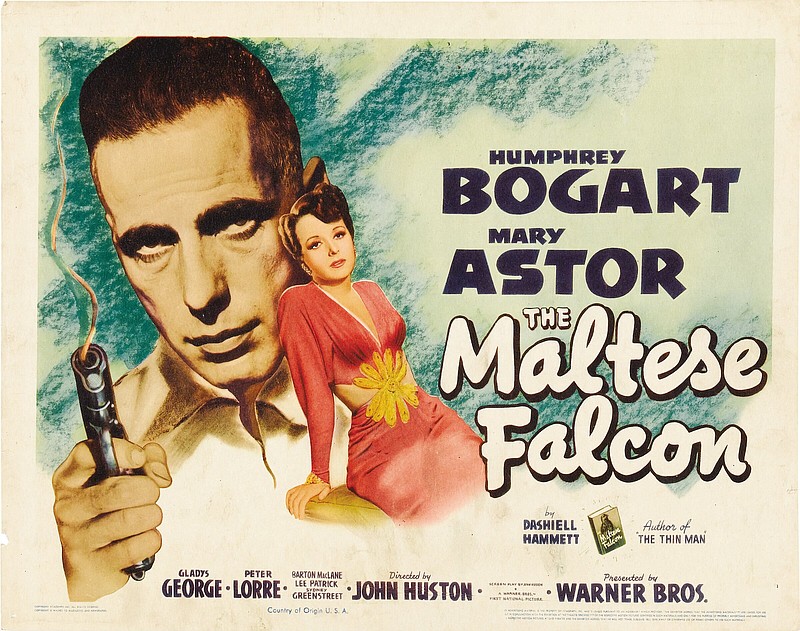

While the term was in use by French writers as early as the late 1930s, it was first applied specifically to Hollywood movies in a French film journal in August 1946. That article examined the congruities among five shadow-drenched American films that had recently opened in Paris: Billy Wilder's "Double Indemnity," Edward Dmytryk's "Murder, My Sweet," Otto Preminger's "Laura " (all 1944), Wilder's "The Lost Weekend" (1945) and "The Maltese Falcon," released in October 1941.

The French critics were using the term exclusively to describe Hollywood product; even as it seems to present a template for the genre, Fritz Lang's German-made 1931 film "M" would not strictly qualify as a film noir, but the 1951 Joseph Losey remake of that film would.

Louis Feuillade's "Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine" (1913) and D.W. Griffith's "The Musketeers of Pig Alley" (1912) are sometimes cited as early examples of the genre, and someone could likely make a case for any number of films that feature cynical characters and ominous settings. But criticism, like poetry, sometimes benefits from bright line rules and arbitrary decisions. The more tightly we define "film noir," the better we might understand one another.

BIRTH OF FILM NOIR

Paul Schrader, the filmmaker ("First Reformed," "Taxi Driver") and critic, in his essay "Notes on Film Noir," contends there were four elements present in 1940s Hollywood that fomented the birth of film noir.

The first was disillusionment brought on by World War II. Many films of the 1930s and early 1940s were highly escapist, designed to raise public morale in the face of the Depression and the inevitable war (if the War to End All Wars ended at all, it ended on an suspended, unsatisfying chord that everyone understood would eventually resolve in blood).

The second element, Schrader contends, was post-war realism. Disillusioned American audiences were ready to be challenged by an authenticity lacking in the stylized musicals and high-class melodramas of the 1930s; the familiar, idealized studio backlot sets were beginning to feel stale and phony.

It was more exciting and involving to watch actors performing in real, recognizable locations (or what seemed like real locations). Writing and dialogue became more naturalistic, as movie acting further diverged from stage acting.

A third element was the influence of German and eastern European directors like Lang and Wilder, who immigrated to Hollywood in the '30s as Nazism became ascendent, bringing with them aesthetics influenced by German Expressionism, a style marked by dramatic lighting and an understanding of psychological possibilities of mise-en-scene -- stage design and the way characters are put before the camera.

Finally, Schrader notes the influence of writers such as Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain with their "hard-boiled' style -- a cynical, tough and urban main protagonist opposed by deeply corrupt forces.

The typical film noir features a flawed but questing character reluctantly engaged by an innocent party to investigate a monstrous, entrenched conspiracy within a respectable institution. While the main character (let's not call him a hero) usually survives and extracts a measure of justice on behalf of his client, his victories are meager and sometimes pyrrhic. Even if the bad guys are brought to justice, there are others waiting to take their place.

WHAT CONSTITUTES FILM NOIR

Schrader points out that "film of urban nightlife is not necessarily a film noir, and a film noir need not necessarily concern crime and corruption."

"The Maltese Falcon" (1941) is often called the first noir film, but that's not correct. It's not even Bogart's first noir -- he was in Raoul Walsh's "They Drive By Night," released 14 months earlier. Latvian-born Soviet-trained Boris Ingster's "Stranger on the Third Floor," which features "M" star Peter Lorre, were both released in 1940. We can't even call "The Maltese Falcon" the first film noir even if we make an arbitrary ruling that only movies released after the U.S. entry into World War II be considered -- "Falcon" was released in October 1941.

It's a shame the movie has been certified as a "great film," which means we are supposed to appreciate it, to notice how certain gestures and modes of behavior on display have become encoded in the culture, how people who have never seen the movie sometimes seem to be acting it out.

The best way to see any movie is to come into it with no expectations, open to the possibility that it might change your life. But it is impossible for a modern viewer to encounter "The Maltese Falcon" on the same terms its first audience encountered it. For all they knew, those people of the past were just going to the movies. They set out with the same expectations (and lack of expectations) that we might hold for any popular entertainment. They hoped to be engaged and diverted from what was humdrum or unpleasant about their lives.

Pearl Harbor was still a couple of months away, but sentient beings knew the world was troubled. They went to see "The Maltese Falcon" because they went to the movies every week, because the poster promised them "a story as explosive as his blazing automatic."

Consider that Hammett's 1929 novel had been filmed twice before, first in 1931, under the same title (sometimes this version is known as "Dangerous Female") with Ricardo Cortez as cynical anti-hero Sam Spade. In 1936, Bette Davis was directed by William Dieterle in "Satan Met a Lady." The detective, played by Warren William, is called Ted Shane instead of Sam Spade, but it is the same story.

So there was no reason for the typical moviegoer to expect "The Maltese Falcon" was going to be exceptional. Bogart had not yet become Bogart. He was a solid supporting player who'd gotten a break the year before when George Raft and Paul Muni turned down the lead role in the gangster film "High Sierra." (Raft reportedly passed on the film because he didn't want to die in the end.)

"High Sierra" had been a surprise hit but not a cinematic landmark. It did give screenwriter John Huston a chance to direct his first movie.

CLOSE TO THE NOVEL

"The Maltese Falcon" is very close to Hammett's novel. Much of the dialogue comes directly from the book. (Not, however, Sam Spade's final line, a Shakespearean allusion that Bogart, according to legend, ad-libbed.) But Bogart looks nothing like the "blond satan" Hammett describes. In the book, Caspar Gutman, aka "The Fat Man," is heavier than Sydney Greenstreet (in his first movie role). Mary Astor makes for a rather matronly femme fatale; she has about her a soft-toned air of money that isn't suggested in the book.

But Huston understood Hammett's novel was not really about the convoluted plot so much as it was about character. It doesn't matter who killed Sam Spade's partner Miles Archer, the film's central mystery, but how the various characters glance off one another, the style they exhibit, the wary yet frank way the predators -- sexual and otherwise -- regard their prey.

Is it this quality that makes "The Maltese Falcon" the first film noir? Certainly those moviegoers in 1941 would not have called it that. Not even the French would have called it that. Not then.

Huston and Bogart were not trying to create a new film genre; more likely they were simply working to improve on the pulpy gangster films of the 1930s with which genuine film noir is sometimes confused.

"The Maltese Falcon" and the noir films that followed do not generally portray crime as a glamorous profession or criminals as particularly strong characters. Crime is something weak that vulnerable people fall into out of desperation, lust or accident.

Women in these films, frequently stronger than the men they bewitch, are more often presented as temptress than as victim. Film noir chronicles the stunted lives of losers and grifters; it is populated with disillusioned detectives and bitter, damaged loners.

Bogart's Spade is the template for the noir hero -- or anti-hero. Hard and unsentimental, willing to credit any motivation other than self-interest, Spade never liked his murdered partner, and he puts the moves on the widow as soon as he gets a chance.

He relishes the opportunity to beat up homosexual (he carries a perfumed handkerchief) Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), even though the violence is probably unnecessary. He is even willing to let the woman he "maybe" loves take her chances with the gas chamber.

Spade isn't beholden to any bonds of human affection, but does adhere to a strict code of professional conduct. When a man's partner is murdered, the man is compelled to do something about it. To let a killer get away with murder is "bad for business."

CHARACTERS IN SHADOW

In terms of style and technique, film noir leaves its characters in the shadows; these creatures live at night in a lurid world lit by neon and glowing cigarettes. The exaggeratedly shabby sets suggest something of the naturalism of the books of Frank Norris or Theodore Dreiser as well as the pulp detective novels -- Hammett, Chandler, Jim Thompson -- from which the movies draw story lines.

In 1941, another first-time director, Orson Welles, made a splash with an audacious, ambitious movie designed to show Hollywood a better way to tell stories. "Citizen Kane" was not a popular favorite, but its flashy technical innovation couldn't be dismissed. Huston also gave a lot of thought and care to camera movement and shot composition, but the great triumph of "The Maltese Falcon" is that the average moviegoer is never compelled to take notice of the camera's machinations.

Unlike some of the other films associated with film noir -- especially Howard Hawks' 1946 "The Big Sleep" (in which Bogart played Chandler's detective Philip Marlowe, a softer version of the Spade character), George Cukor's "Gaslight" (1944) and Robert Aldrich's "Kiss Me Deadly"(1955) -- "The Maltese Falcon" never seems self-consciously arty.

We simply watch and are pulled along by the dark wit, the way Sam Spade banters with Gutman over the value and whereabouts of the titular black bird. Spade gets angry, smashes his glass on the floor and stomps out.

In the hallway, Spade grins at his performance as a "man with a very violent temper." Today we might see in that shot the well-bred Bogart -- son of a Manhattan surgeon and a successful magazine illustrator -- commenting on his act as the tough guy Spade, a role he couldn't have known would define the rest of his movie career and establish him as an essential American icon. (Acting is, as Bogart would later concede, "the softest of rackets.")

Likewise, John Huston was a screenwriter, not the monument he is today. If, in 1941, anyone was drawing up lists of the best 100 movies of all time, no one was paying much attention to them. We cannot see "The Maltese Falcon" with innocent eyes, without at least a faint sense of musty obligation.

It has acquired this patina of importance, because part of what makes a film great is its power to obliterate whatever preconceptions we bring to it. There is brittleness and sparkling harm and a very adult sense of fun in "The Maltese Falcon"; it still works as a movie, as a diversion. It is still much more a reprieve from duty than a duty itself.

Email:

pmartin@adgnewsroom.com