Dr. Patricia Griffen, a psychologist and former president of the Arkansas Psychological Association, criticized the American Psychological Association for its recent apology to communities of color during a panel discussion on Wednesday.

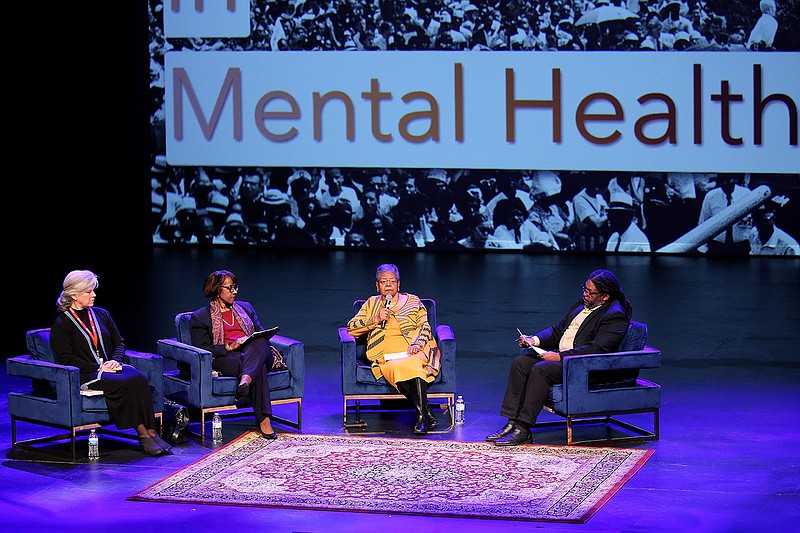

The panel, which convened at the University of Arkansas-Pulaski Technical College, focused on inequity in mental health. Besides Griffen, other panelists were Elizabeth Eckford of the Little Rock Nine and Mary Kate Terrell, who teaches sociology at Pulaski Tech. Mayo Johnson, assistant professor of computer science at the college, led the discussion.

The American Psychological Association's apology to people of color for its role in contributing to systematic racism was released 130 years after its founding, Griffen said. She read a statement from the Association of Black Psychologists released after the apology was issued:

"'The APA has played a large hand in the oppression of the Black community in education, health, housing, the media, the work sector, criminal justice and practically all domains of life necessary to thriving and optimal well-being.'

"APA historically has been complicit, and there are some issues that APA still needs to address."

Griffen noted that the American Psychological Association did not include in their apology the fact that they were a promoter of racial hierarchy, comparative research studies trying to show the hierarchy of Black people using IQ test scores.

"Dr. Robert L. Williams is a victim of [IQ testing] and he went on to challenge IQ testing and the misuse of it. All of these were initiatives led by APA," she said. "They still have a lot of work to do."

Eckford, a civil rights leader and one of the Little Rock Nine, Black students who desegregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957, brought up the focus on punishment over diagnosis in education when it comes to mental health.

Griffen agreed that "it's painful" to see what is occurring in schools for students at an early age.

"Kindergarteners are being punished for emotional, mental issues," she said. "Efforts are underway to address this. But more needs to be done to address the pain that a lot of children are bringing into these school systems from home. And this is a very serious problem. The course of their lives is charted many times from decisions that are made in kindergarten, and it's very difficult to change that trajectory. This is something that [the Association of Black Psychologists] plans to address later in the year."

Terrell agreed that issues labeled as "behavior issues" are cries for help. How students are treated when they ask for help influences whether they reach out for help in the future.

On the other hand, Terrell said, the underfunding in education causes society to put it on teachers to be "psychologists" when they are not.

Johnson asked panelists what can be done to address mental health services provided in law enforcement to prevent the school-to-prison pipeline.

Griffen said there is a political crisis in the country with the criminalization of mental health issues.

"Individuals who have been incarcerated because of mental health issues that were never treated ... this is why it's so important for mental health professionals to be a part of the police system," she said. "This is an initiative that our organization of Black social workers have been addressing and there is a need for mental health trained professionals to work with our police officers to circumvent this prison pipeline ... There are some states where this is taking place; there are models for this."

Terrell mentioned that if the police force itself had mental health support groups or therapy for the "stressful situations" they experience, then it would be "less of a leap" to consider a possibility of mental health issues among alleged perpetrators.

Griffen said she was very encouraged by the responses from students during the Q&A portion of the event.

"Their awareness, first of all, of the problem and their concerns about getting involved," she said. "It was very encouraging ... for this younger generation to be in the audience and for them to raise the level of questions that they have, and express a desire to get involved and dealing with the issues that we're seeing in our communities."

Terrell said she wanted students to remember that their voice matters.

"They have the power to begin in whatever direction, whether it is that agency that already exists that they just want to change one at a time or in the political realm for policies that are much bigger than a local agency," she said.

Griffen agreed, and added that students don't have to take on these issues "on their own," but can work with organizations to be "empowered."

Eckford recalled when she was confronted by white students while trying to attend school at Little Rock Central High.

"When you choose not to act, you have made a decision -- that is a decision," she said. "We're all responsible for the kind of community we have."

Few white people interacted with Black people in a "friendly way," Eckford said, because they would receive "threatening calls" or were "physically attacked."

Had there been more white people supporting the Little Rock Nine in their effort, then they couldn't have been isolated, she said.

"But you can't expect the majority of people to empathize and reach out to support someone who's being harassed. But I try to let people know how important and how powerful language can be ... If they just treat people the way they want to be treated, that can be very powerful for somebody who's been set apart and hated upon."