WASHINGTON -- The House voted unanimously Friday to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of covid-19, a sweeping show of bipartisan support as today marks the third anniversary of the day the World Health Organization first called the outbreak a pandemic.

The global death toll is nearing 7 million.

Friday's 419-0 House vote was final congressional approval of the bill, sending it to President Joe Biden's desk. It's unclear whether the president will sign the measure into law, and the White House said the matter was under review.

"I haven't made that decision yet," Biden said Friday when asked whether he would sign the bill.

Debate in the House was brief and to the point: Americans have questions about how the deadly virus started and what can be done to prevent future outbreaks.

"The American public deserves answers to every aspect of the covid-19 pandemic," said Rep. Michael Turner, R-Ohio, the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee.

That includes, he said, "how this virus was created and, specifically, whether it was a natural occurrence or was the result of a lab-related event."

The order to declassify focused on intelligence related to China's Wuhan Institute of Virology, citing "potential links" between the research that was done there and the outbreak of covid-19, which the World Health Organization declared a pandemic March 11, 2020.

U.S. intelligence agencies are divided over whether a lab leak or a spillover from animals is the likely source of the deadly virus.

Experts say the true origin of the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed more than 1 million Americans, may not be known for many years -- if ever.

"Transparency is a cornerstone of our democracy," said Rep. Jim Himes, of Connecticut, the top Democrat on the Intelligence Committee, during the debate.

Led by Republicans, the focus on the virus origins comes as the House launched a select committee with a hearing earlier in the week delving into theories about how the pandemic started.

It offers a rare moment of bipartisanship despite the often heated rhetoric about the origins of the coronavirus and the questions about the response to the virus by U.S. health officials, including former top health adviser Anthony Fauci.

The legislation from Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., was already approved by the Senate. Hawley urged Biden to sign the bill into law.

"The American people deserve to know the truth," he said in a statement.

If signed into law, the measure would require within 90 days the declassification of "any and all information relating to potential links between the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the origin of the Coronavirus Disease."

That includes information about research and other activities at the lab and whether any researchers grew ill.

DECISIONS IN ARKANSAS

Early in the pandemic, then-Gov. Asa Hutchinson issued orders closing schools and businesses such as casinos, bars, gymnasiums, movie theaters and hair salons and barring indoor dining in restaurants.

The state Department of Health under Hutchinson also issued a directive March 26, 2020, prohibiting indoor gatherings of more than 10 people. The directive did not apply to places of worship and certain other locations, such as factories and government bodies.

"I insisted upon no restrictions on churches or houses of worship and in the fall of 2020 I made it clear we were keeping our schools open for in classroom instruction. As a result, Arkansas ranked second of all the states in days of in-classroom teaching during the pandemic," Hutchinson said in response to questions from the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. "We didn't do it perfectly because we didn't know everything about the virus, but all in all, Arkansas stepped up and balanced keeping our economy open with the healthcare needs of our citizens."

The March 26, 2020, directive gave the state health secretary the discretion to exercise his authority even for those venues if he believed the public's health were at risk. Hutchinson noted Friday, however, that the restrictions in Arkansas didn't go as far as those that were implemented in many other states.

"A manufacturer in a non-essential business recently thanked me for standing up against the pressure and not 'sheltering in place' as the majority of states did," Hutchinson said. "He said his business has tripled because other states in the Northeast closed his competitors down. Not giving in to the national pressure on closing businesses was one of the best decisions I made."

Most people have resumed their normal lives, thanks to a wall of immunity built from infections and vaccines. The virus appears here to stay, along with the threat of a more dangerous version sweeping the planet.

"New variants emerging anywhere threaten us everywhere," said virus researcher Thomas Friedrich of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "Maybe that will help people to understand how connected we are."

The United Nations' health organization says it's not yet ready to say the emergency has ended.

With the pandemic still killing 900 to 1,000 people a day worldwide, the stealthy virus behind covid-19 hasn't lost its punch. It spreads easily from person to person, riding respiratory droplets in the air, killing some victims but leaving most to bounce back without much harm.

"Whatever the virus is doing today, it's still working on finding another winning path," said Dr. Eric Topol, head of Scripps Research Translational Institute in California.

Topol said the country has become numb to the daily death toll, but it should be viewed as too high. Consider that in the United States, daily hospitalizations and deaths, while lower than at the worst peaks, have not yet dropped to the low levels reached during summer 2021 before the delta variant wave.

At any moment, the virus could change to become more transmissible, more able to sidestep the immune system or more deadly. Topol said the world is not ready for that.

SCIENTIFIC LEGACY

Trust has eroded in public health agencies, furthering an exodus of public health workers. Resistance to stay-at-home orders and vaccine mandates may be the pandemic's legacy.

"I wish we united against the enemy -- the virus -- instead of against each other," Topol said.

Humans unlocked the virus' genetic code and rapidly developed vaccines that work remarkably well. Mathematical models were built to get ready for worst-case scenarios. Monitoring continues on how the virus is changing by looking for it in wastewater.

"The pandemic really catalyzed some amazing science," said Friedrich.

The achievements add up to a new normal where covid-19 "doesn't need to be at the forefront of people's minds," said Natalie Dean, an assistant professor of biostatistics at Emory University. "That, at least, is a victory."

Dr. Stuart Campbell Ray, an infectious-disease expert at Johns Hopkins, said the current omicron variants have about 100 genetic differences from the original coronavirus strain. That means about 1% of the virus's genome is different from its starting point.

Many of those changes have made it more contagious, but the worst is likely over because of population immunity.

Matthew Binnicker, an expert in viral infections at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said the world is in "a very different situation today than we were three years ago -- where there was, in essence, zero existing immunity to the original virus."

That extreme vulnerability forced measures aimed at "flattening the curve." Businesses and schools closed, weddings and funerals were postponed. Masks and "social distancing" later gave way to showing proof of vaccination. Now, such precautions are rare.

"We're not likely to go back to where we were because there's so much of the virus that our immune systems can recognize," Ray said. Our immunity should protect us "from the worst of what we saw before."

REAL-TIME DATA LACKING

Johns Hopkins did its final update Friday to its free coronavirus dashboard and hot-spot map with the death count standing at more than 6.8 million worldwide. Its government sources for real-time tallies had drastically declined.

In the U.S., only New York, Arkansas and Puerto Rico still publish case and death counts daily.

"We rely so heavily on public data and it's just not there," said Beth Blauer, data lead for the project.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still collects a variety of information from states, hospitals and testing labs, including cases, hospitalizations, deaths and what strains of the coronavirus are being detected. But for many counts, there's less data available now and it's been less timely.

"People have expected to receive data from us that we will no longer be able to produce," said the CDC's director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky.

In the three years since the first Arkansas case was recorded, the state has totaled 1,007,200 cases and 13,027 deaths, according to the Health Department.

Of the state's 75 counties, Pulaski County has seen the most deaths -- 1,323. According to the Health Department's online dashboard, 2,551 of the covid deaths in Arkansas have been in nursing homes and 62 have been in correctional facilities.

The latest update from the Health Department reported 2,746 cases in the state that were active as of Friday.

Internationally, the WHO's tracking of covid-19 relies on individual countries reporting. Global health officials have been voicing concern that their numbers severely underestimate what's actually happening and they do not have a true picture of the outbreak.

For more than year, CDC has been moving away from case counts and testing results, partly because of the rise in home tests that aren't reported. The agency focuses on hospitalizations, which are still reported daily, although that may change. Death reporting continues, though it has become less reliant on daily reports and more on death certificates -- which can take days or weeks to come in.

U.S. officials say they are adjusting to the circumstances, and trying to move to a tracking system somewhat akin to how CDC monitors the flu.

THEN AND NOW

On March 11, 2020, Arkansas recorded its first covid-19 case in a Pine Bluff patient. The state's peak for new cases didn't come until Jan. 15, 2022, when it had a daily average of 8,968, according to data from The New York Times.

"We had already prepared for the first case even though we knew very little about the virus," Hutchinson said Friday. "At that time, I was grateful for my crisis management experience in the post 9/11 threat environment while I was at the [U.S.] Department of Homeland Security. I am most thankful for the healthcare professionals who served the people of Arkansas so bravely and with such dedication."

Kelly Forrester, 52, of Shakopee, Minn., lost her father to the disease in May 2020, survived her own bout in December and blames misinformation for ruining a longtime friendship.

"I wish we could go back to before covid," she said "I hate it. I actually hate it."

The disease feels random to her. "You don't know who will survive, who will have long covid or a mild cold. And then other people, they'll end up in the hospital dying."

Forrester's father, 80-year-old Virgil Michlitsch, a retired meat packer, deliveryman and elementary school custodian, died in a nursing home with his wife, daughters and granddaughters keeping vigil outside the building in lawn chairs.

Not being at his bedside "was the hardest thing," Forrester said.

Inspired by the pandemic's toll, her 24-year-old daughter is now getting a master's in public health.

"My dad would have been really proud of her," Forrester said. "I'm so glad that she believed in it, that she wanted to do that and make things better for people."

Information for this article was contributed by Lisa Mascaro, Seung Min Kim, Carla K. Johnson, Laura Ungar and Mike Stobbe of The Associated Press and by Daniel McFadin of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

FILE - This 2020 electron microscope image made available by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, which cause COVID-19. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19, a sweeping show of bipartisan support near the third anniversary of the start of the deadly pandemic. (Hannah A. Bullock, Azaibi Tamin/CDC via AP, File)

FILE - This 2020 electron microscope image made available by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, which cause COVID-19. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19, a sweeping show of bipartisan support near the third anniversary of the start of the deadly pandemic. (Hannah A. Bullock, Azaibi Tamin/CDC via AP, File) FILE - A person is taken on a stretcher into the United Memorial Medical Center after going through testing for COVID-19 Thursday, March 19, 2020, in Houston. On the third anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2023, the virus is still spreading and the death toll is nearing 7 million worldwide. Yet most people have resumed their normal lives, thanks to a wall of immunity built from infections and vaccines. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip, File)

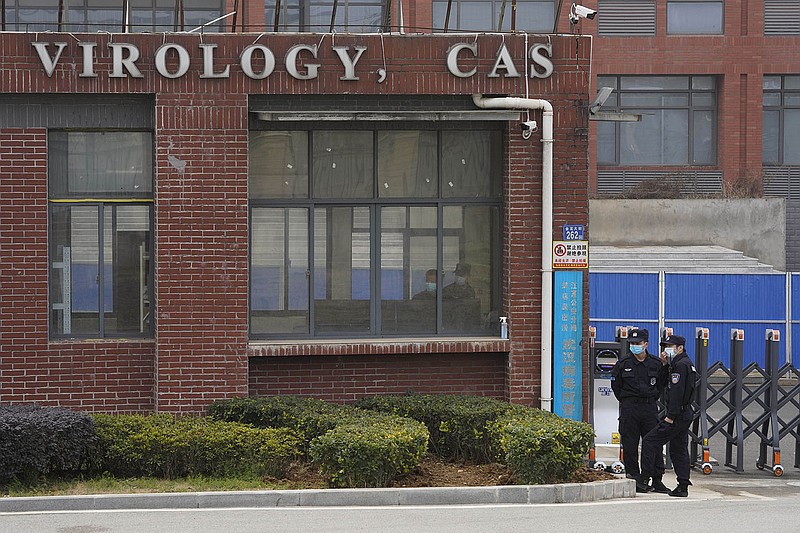

FILE - A person is taken on a stretcher into the United Memorial Medical Center after going through testing for COVID-19 Thursday, March 19, 2020, in Houston. On the third anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2023, the virus is still spreading and the death toll is nearing 7 million worldwide. Yet most people have resumed their normal lives, thanks to a wall of immunity built from infections and vaccines. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip, File) FILE - A view of the P4 lab inside the Wuhan Institute of Virology is seen after a visit by the World Health Organization team in Wuhan in China's Hubei province on Feb. 3, 2021. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19. The order to declassify focused on intelligence related to China's Wuhan Institute of Virology, citing "potential links" between the research that was done there and the outbreak of COVID-19, which the WHO declared a pandemic in March 2020. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File)

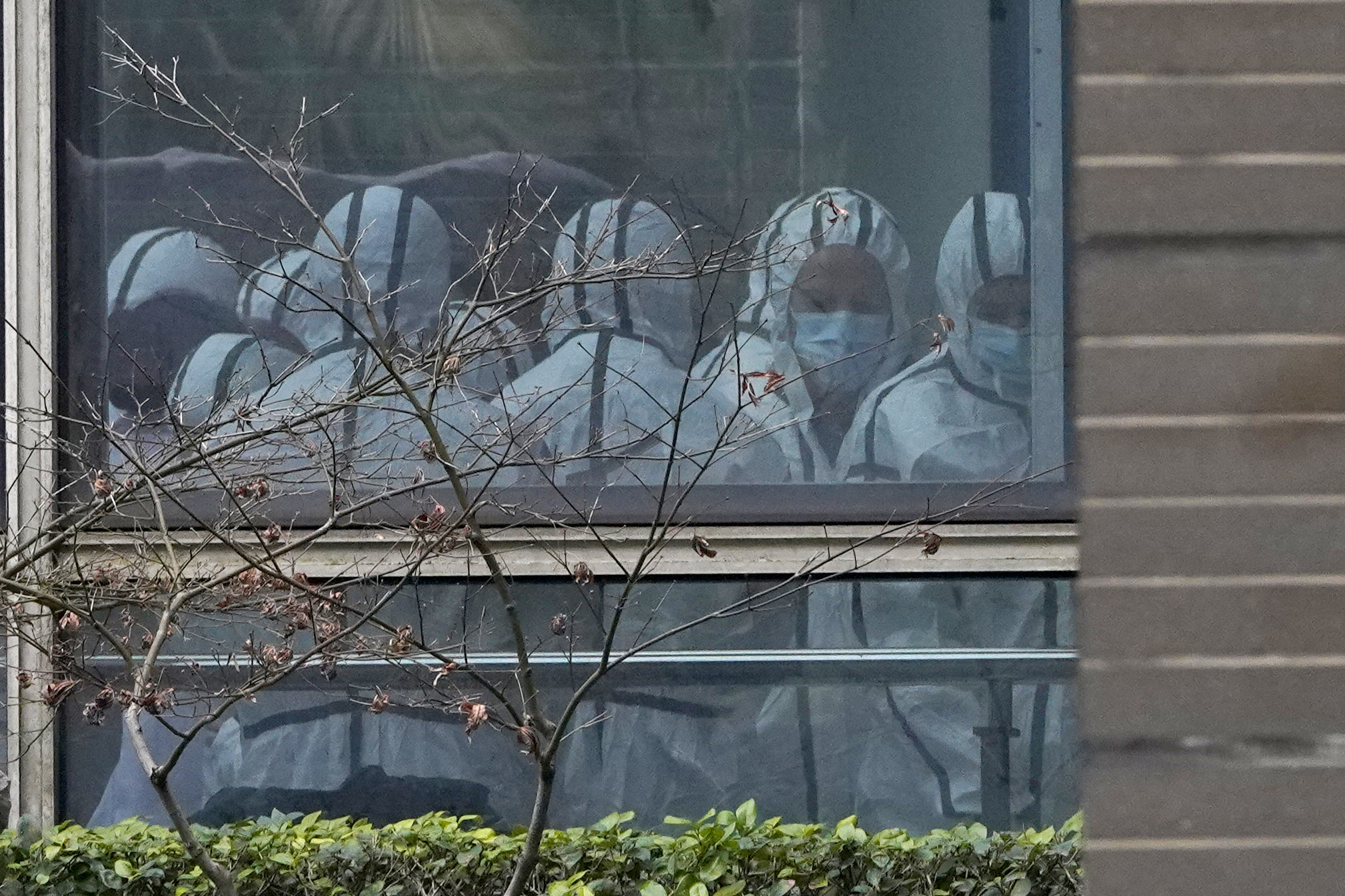

FILE - A view of the P4 lab inside the Wuhan Institute of Virology is seen after a visit by the World Health Organization team in Wuhan in China's Hubei province on Feb. 3, 2021. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19. The order to declassify focused on intelligence related to China's Wuhan Institute of Virology, citing "potential links" between the research that was done there and the outbreak of COVID-19, which the WHO declared a pandemic in March 2020. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File) FILE - Members of a World Health Organization team are seen wearing protective gear during a field visit to the Hubei Animal Disease Control and Prevention Center for another day of field visit in Wuhan in central China's Hubei province Feb. 2, 2021. The WHO team was investigating the origins of the coronavirus pandemic has visited two disease control centers in the province. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19, a sweeping show of bipartisan support near the third anniversary of the start of the deadly pandemic. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File)

FILE - Members of a World Health Organization team are seen wearing protective gear during a field visit to the Hubei Animal Disease Control and Prevention Center for another day of field visit in Wuhan in central China's Hubei province Feb. 2, 2021. The WHO team was investigating the origins of the coronavirus pandemic has visited two disease control centers in the province. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19, a sweeping show of bipartisan support near the third anniversary of the start of the deadly pandemic. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File) FILE - Government workers stand outside a blue tent used to coordinate transportation of travelers from Wuhan to designated quarantine sites in Beijing, April 15, 2020. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19, a sweeping show of bipartisan support near the third anniversary of the start of the deadly pandemic. (AP Photo/Sam McNeil, File)

FILE - Government workers stand outside a blue tent used to coordinate transportation of travelers from Wuhan to designated quarantine sites in Beijing, April 15, 2020. The House voted unanimously Friday, March 10, 2023, to declassify U.S. intelligence information about the origins of COVID-19, a sweeping show of bipartisan support near the third anniversary of the start of the deadly pandemic. (AP Photo/Sam McNeil, File)