The murder conviction of a Marion man sentenced to two life terms plus an additional 835 years in the death of a police officer has been thrown out by a divided Arkansas Supreme Court because Crittenden County authorities took too long to bring the 29-year-old defendant to trial, violating his Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial.

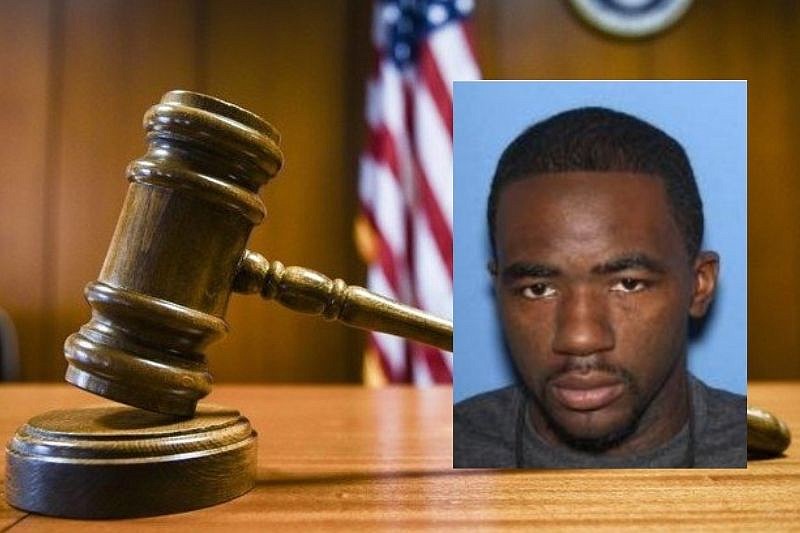

Unless state lawyers can get the justices to reconsider, Demarcus Donnell Parker will be released from prison after almost five years in custody, with his convictions for first-degree murder, six counts of attempted first-degree murder, and 21 counts of discharge of a firearm from a vehicle forever vacated along with his prison sentence.

Parker's co-defendant, 26-year-old George Jealvontia Henderson of West Memphis, was given immunity from the charges in exchange for cooperating with then-prosecutor Scott Ellington, who was the 2nd Judicial District elected prosecuting attorney at the time.

Oliver Johnson Jr., 25, was an off-duty Forrest City police officer who lived in the Meadows Apartments on South Avalon Street in West Memphis, according to officials. A father of two daughters and engaged to be married, Johnson was in his residence playing video games about 3:30 p.m. on April 28, 2018, with his niece and other children when a shoot-out between rival gang members began outside. Witnesses reported hearing at least 40 gunshots. Henderson and Parker, who has a Gangster Disciples tattoo, were arrested about two weeks later in May 2018.

Arkansas' speedy trial rules require defendants to be brought to trial within a year of arrest. If the defendant is jailed, that time can be reduced to nine months in certain circumstances. Judges can extend that time if they find there's good reason, as provided for by the court's procedural rules, for a delay. If a defendant can make a good argument his trial rights have been violated, prosecutors have to prove to the court the defendant's rights were respected.

Writing for the high court, Chief Justice Dan Kemp found that the presiding judge, Randy Philhours of the Second Judicial Circuit that contains Clay, Craighead, Crittenden, Greene, Mississippi and Poinsett counties, allowed too much time to pass before Parker's September 2020 jury trial, exceeding the one-year limit by 40 days.

"Accordingly, we are left with no choice but to reverse and dismiss," Kemp's 22-page ruling states. "If the defendant is not brought to trial within the requisite time, the defendant is entitled to have the charges dismissed with an absolute bar to prosecution. The constitutional right to a speedy trial, as embodied in Rule 28.1 of the Arkansas Rules of Criminal Procedure, is available to an accused in all criminal prosecutions. The Sixth Amendment provides, 'In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial.'"

Parker was represented on appeal by Little Rock attorney Michael Kaiser, but the speedy trial issue was first raised before Philhours by his trial attorneys, Carter Dooley of Wynne and Bryan Donaldson of Fayetteville. They convinced Philhours that Parker's trial rights were in jeopardy after he'd spent nine months in jail, which resulted in the judge releasing Parker on his own recognizance in December 2019.

However, Philhours rejected the defense's later arguments that Parker was entitled to have the charges dropped because the proceedings had taken too long, court records show.

Parker's freedom lasted about five weeks before he was arrested by West Memphis police who reported finding him with a stolen gun, court records show. The felony theft by receiving charge was dropped after his conviction.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Rhonda Wood described the importance of the speedy trial right.

"This rule protects the accused from languishing in jail while awaiting trial and ensures a swift chance to clear their name," she wrote. "The right to a speedy trial is essential to our justice system. And our laws must be applied equally to the guilty and innocent alike. It is easier to uphold the rule of law when the accused is innocent. It is not so easy when a jury found the defendant guilty. Yet we must uphold the rule of law for everyone."

The defendant was held for 846 days before facing trial, Wood noted. Proceedings sometimes were rescheduled because the court was too busy to adequately conduct those hearings, and while those "docket congestion" delays can be legitimate, the judge did not adequately document them, according to Wood.

There were missing records too because important discussions about trial delays "happened during an off-the-record conversation partly in a judge's office and partly in a hallway," Wood wrote, noting that "while there were later many excuses they were not extraordinary ones."

In his dissent, Justice Shawn Womack opened by vividly recounting the officer's death, which was witnessed by five children.

"In a gang-inspired and retaliatory drive-by shooting, Parker fired a barrage of bullets at a group of teenagers standing outside Officer Johnson's apartment," he wrote. "Once the shooting ceased, Officer Johnson's niece -- who was at the home with him and four other children -- discovered her uncle lying on his bedroom floor, shaking, because Parker had just shot him in the arm and chest. Officer Johnson died in front of the children."

Womack complained the ruling majority had used the wrong standard to consider when trial delays are appropriate and that "Parker has cleverly pulled the wool over the majority's eyes." Philhours, the presiding judge, found good reason to grant delays, and his fellow justices broke with precedent by not accepting his reasoning, particularly in a complicated case like the defendant's, Womack stated.

"We routinely defer to a circuit court's finding of fact, which is what this is," he stated. "Yet here, the majority concludes, with few details and little analysis, that the circuit court's understanding of its docket, the ability of the parties, and the pace of litigation is inferior to the majority's own understanding of the three. Seemingly, the majority has simply--and wrongfully--substituted its judgment for the judgment and memory of the circuit court."

Joining with Womack in dissent was Justice Barbara Webb, who had more reasons the majority was wrong. She stated there's never been a clear definition despite 170 years of jurisprudence in Arkansas over what "speedy" means and how the right should be protected.

Webb wrote that she favors a test established in 1972 by the U.S. Supreme Court involving a defendant who waited six years for trial. The federal court favored balancing the conduct of prosecution and defense while taking into account four factors: length of delay, reason for delay, the defendant's assertion of the speedy trial right and how the defendant would be harmed by delay.

Applying that standard, and given reasons for the delay, some of them due to logistics, such as finding an adequate courtroom, and the prosecution efforts to properly prepare, the cumulative delay was a short one that did no harm to Parker, she wrote.