BENTONVILLE — It speaks to the reduced reputation of Mexican artist Diego Rivera in the 21st century that "Diego Rivera's America" is the first major exhibition focused on the artist in more than two decades.

The show, co-organized by Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, opened here March 11 and runs through July 31. It collects more than 130 of Rivera's drawings, easel paintings and frescoes, with video installations depicting some of his murals.

Curated by Wellesley College senior lecturer James Oles and Maria Castro, assistant curator at SFMOMA and coordinated at Crystal Bridges by Jen Padgett, the museum's acting Windgate curator of craft, the exhibition is a thought-stimulating survey of the career of a major artist who has been eclipsed by the pop-culture apotheosis of Frida Kahlo.

Kahlo, Rivera's wife, was a self-taught painter whose work is largely autobiographical and intimate, as opposed to her husband's globe-hugging ambition. She became a feminist icon in the 1970s, some 20 years after her death, largely on the anecdotal strength of her personal story. Disabled by polio as a child, she was a promising student bound for medical school when she was in a bus accident that fractured her spine and pelvis, causing her lifelong pain.

During her recovery, she was forced to wear a full-body cast for three months and began painting as a way to alleviate the boredom. Her first of many self-portraits was completed that first year.

She approached Rivera — whom she had met a few years before when he was painting a mural at her exclusive National Preparatory School in Mexico City some years before — seeking his opinion and advice on her work, and the two were married within the year.

Kahlo's work did not go unnoticed during her lifetime. It was shown and she had commissions, perhaps the most famous one resulting in her shocking painting "The Suicide of Dorothy Hale." Hale was a New York socialite and aspiring actress, the wife of artist Gardner Hale; in 1938, she jumped or fell to her death from the balcony of her Hampshire House residence after coming home from a party at the 21 Club.

Writer and public conservative Clare Boothe Luce immediately commissioned Kahlo to paint a recuerdo (remembrance) of their mutual friend, expecting that Kahlo would deliver a conventional, idealized portrait of Hale. Instead Kahlo presented Luce with a graphic piece that depicts Hale standing on her balcony, in mid-fall and then sprawled dead on the ground.

Luce was appalled by the painting and considered destroying it; she ended up giving it to a friend. It now hangs in the Phoenix Art Museum.

During her lifetime, Kahlo was known more for her tempestuous and unconventional marriage to Rivera (they married twice, divorcing briefly in 1939, and had affairs with the likes of Leon Trotsky, Georgia O'Keeffe, sculptor Isamu Noguchi and possibly Josephine Baker) than her work. (It's interesting to note that there is no entry for her in either the 1970 edition of "The Oxford Companion to Art" or its would-be-comprehensive 1995 revision. The entry on Rivera doesn't mention Kahlo, nor does the one on Mexican art. )

Interest in Kahlo's life and work exploded in 1983, when Hayden Herrera published his bestselling "A Biography of Frida Kahlo." By 2002, when the movie "Frida" was released, there seemed no question that Kahlo was a brighter star than Rivera.

What else might non-specialists in 2023 be expected to know about Rivera other than that he was the husband of Frida Kahlo? He was a communist, disdainful of capitalism, and his most famous paintings — especially narrative murals — were didactic and decorative, employing bold colors and simplified forms that marked a conscious rejection of European techniques in which he was well versed.

Rivera was a true believer; he meant to create "art for the people," and front-loaded allegory into even his most straightforward scenes of working people. Rivera was strident, but also complicated.

At one time, has was seen as a rival to Picasso, a flamboyant figure working toward world revolution who had a legitimate claim to being the most famous artist in the world.

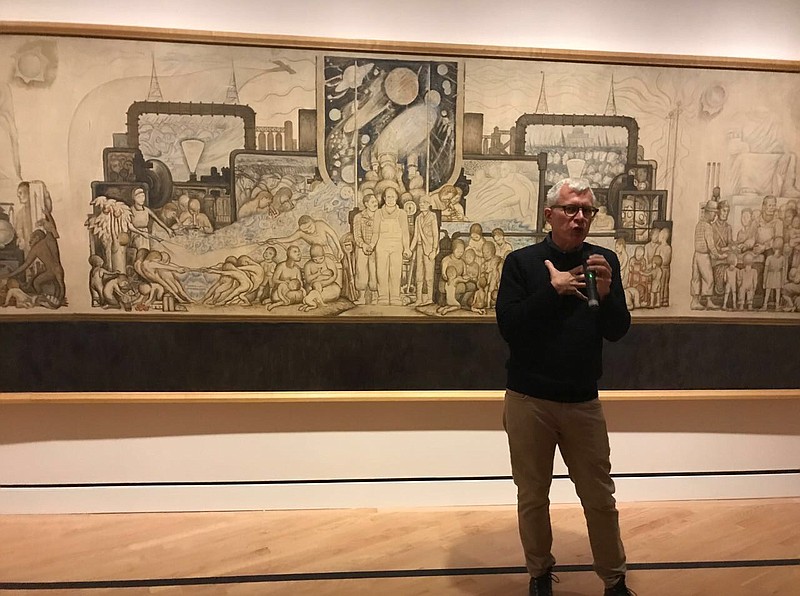

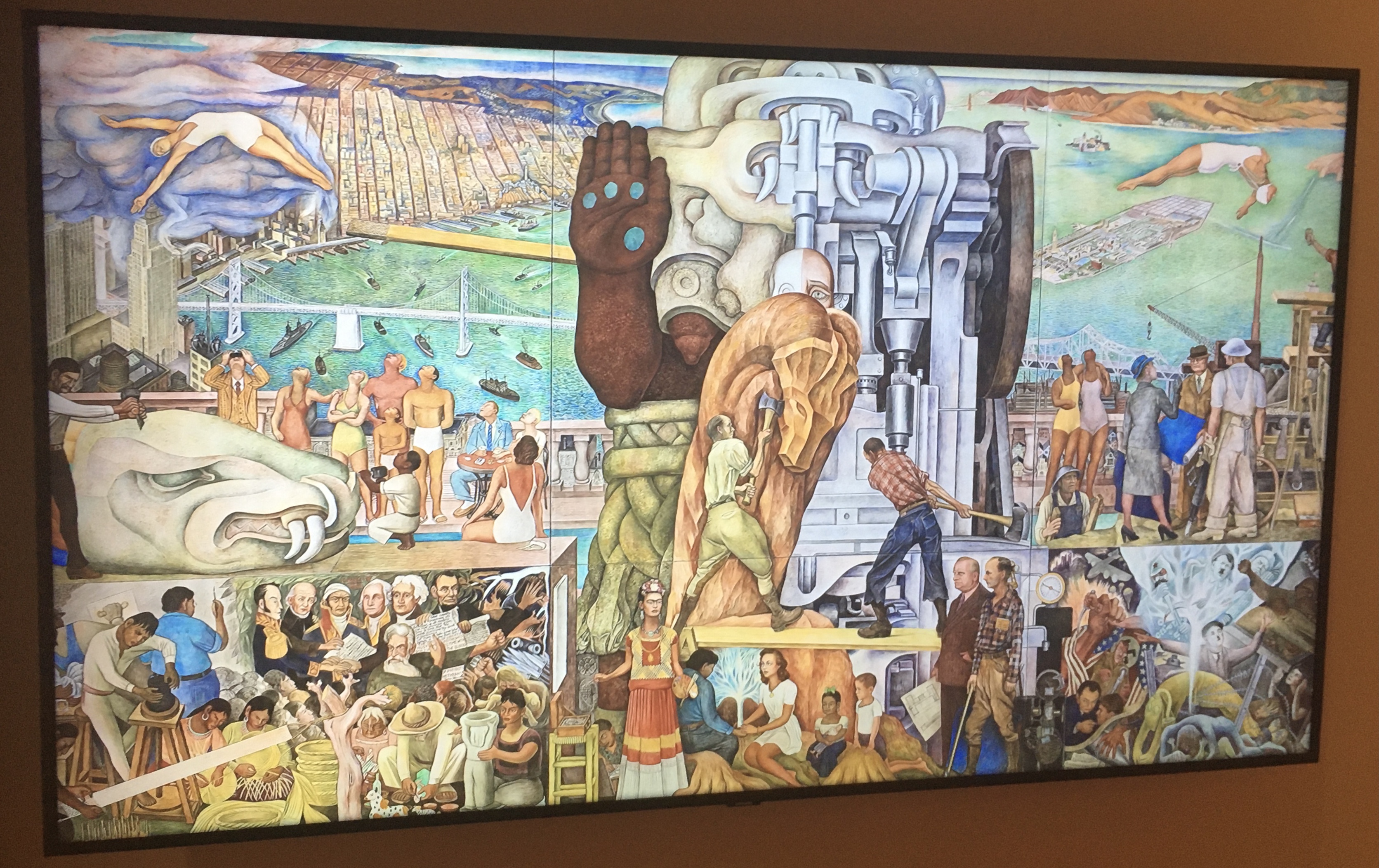

A digital representation of Diego Rivera's massive "Pan American Unity" mural is displayed in the galleries of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville. Visit crystalbrdges.org. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Philip Martin)

A digital representation of Diego Rivera's massive "Pan American Unity" mural is displayed in the galleries of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville. Visit crystalbrdges.org. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Philip Martin)

AN EARLY CALLING

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, in 1886, the son of a well-to-do school inspector.

He was born a twin — his brother Carlos died within two years, and Diego started drawing soon after. When his parents caught him drawing on the walls, they lined the walls with chalkboards and canvas rather than stifle his creativity.

He renounced Catholicism when he was 5 years old, perhaps partially in response to his mother's converso heritage — her Spanish ancestors had been forced to convert from Judaism to Catholicism in the 15th century.

At 10, he entered art school. When he was 20 he headed off to Europe to study and indulge himself. Kahlo was his third and fourth wife out of five; he took countless mistresses.

Like Picasso, he embraced Cubism; he flirted with Post-Impressionism. In Paris, he lived in cheap quarters in Montparnasse and befriended Modigliani, Ilya Ehrenburg, Chaïm Soutine and Max Jacob.

In Paris he found Marxism and an ideological basis for a new kind of painting. Rivera began to weaponize his art, eschewing some of the finer and more nuanced touches of Western practice for a bigger, broader and more democratic approach. He saw easel paintings as frivolous luxury items and modernist conceits as decadent and silly, convoluted filigree that served as bibelots for the ruling class. The only authentically "good" art was art that was literally accessible to all the people — brightly colored murals in public spaces.

When he returned to Mexico in 1921, he found the reform government of President Alvaro Obregon receptive. Rivera and fellow muralists Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros could help win support of the peasant class by giving them something tangible. (When Obregon was assassinated in 1928, leading to the establishment of the Institutional Revolutionary Party — the "PRI," which held power continuously until 2000 — Rivera continued to enjoy the sponsorship of the Mexican government.)

Rivera deliberately abandoned the advanced techniques he'd learned in Europe, painting the walls of Mexico with bold colors and cartoonish figures drained of individual markers (in "Diego Rivera's America" there are several examples where preliminary studies are displayed alongside finished paintings; invariably the studies are more particular and specific and the finished work is more general and idealized). He took inspiration from the art of the Aztecs, rehabilitating a heritage of which Mexicans had been taught for generations to be ashamed.

By 1931, Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros — collectively known as the "new Mexican muralists" — were being courted by Yanqui patrons. Rivera received commissions to paint murals for the California School of Fine Arts and the San Francisco Stock Exchange Club. The Stock Exchange mural "Allegory of California," which is represented by a video installation in the exhibit, depicts tennis champion Helen Willis Moody (an Olympic gold medalist as well as the winner of 31 grand slam events) as a 30-foot-high Calafia, a character from a 16th-century Spanish novel who has come to be known as the Spirit of California.

The mural seems brimming with optimism and a kind of pungent love — the Depression had not yet reached California in 1931 — and Rivera crams into the painting references to the Gold Rush and the oil and shipping industries. A young man holds a model airplane. Absent are the darker elements that seeped into his Mexican compositions — images of corrupt priests and fat cats sipping martinis as workers toiled. Rivera, for once, left out any indication of his radical politics.

Maybe this was a courtesy to his influential friends who'd vowed for more than a year to secure a residency permit for Rivera, who one American artist (who lost out on the Stock Exchange commission) called a "once-avowed Communist." (He had been expelled from the Mexican Communist Party, which he'd help found, for his support of Trotsky.) Or perhaps he was genuinely infatuated with the promise of the Golden State. He certainly didn't want to endanger the $2,500 commission it engendered, the largest of his career to date.

Rivera later acknowledged he was indulging in self-censorship. Two years later, when he found himself embroiled in a controversy over a fresco he had been commissioned to paint for Manhattan's Rockefeller Center called "Man at the Crossroads," he acknowledged he'd been careful with his ideological smuggling.

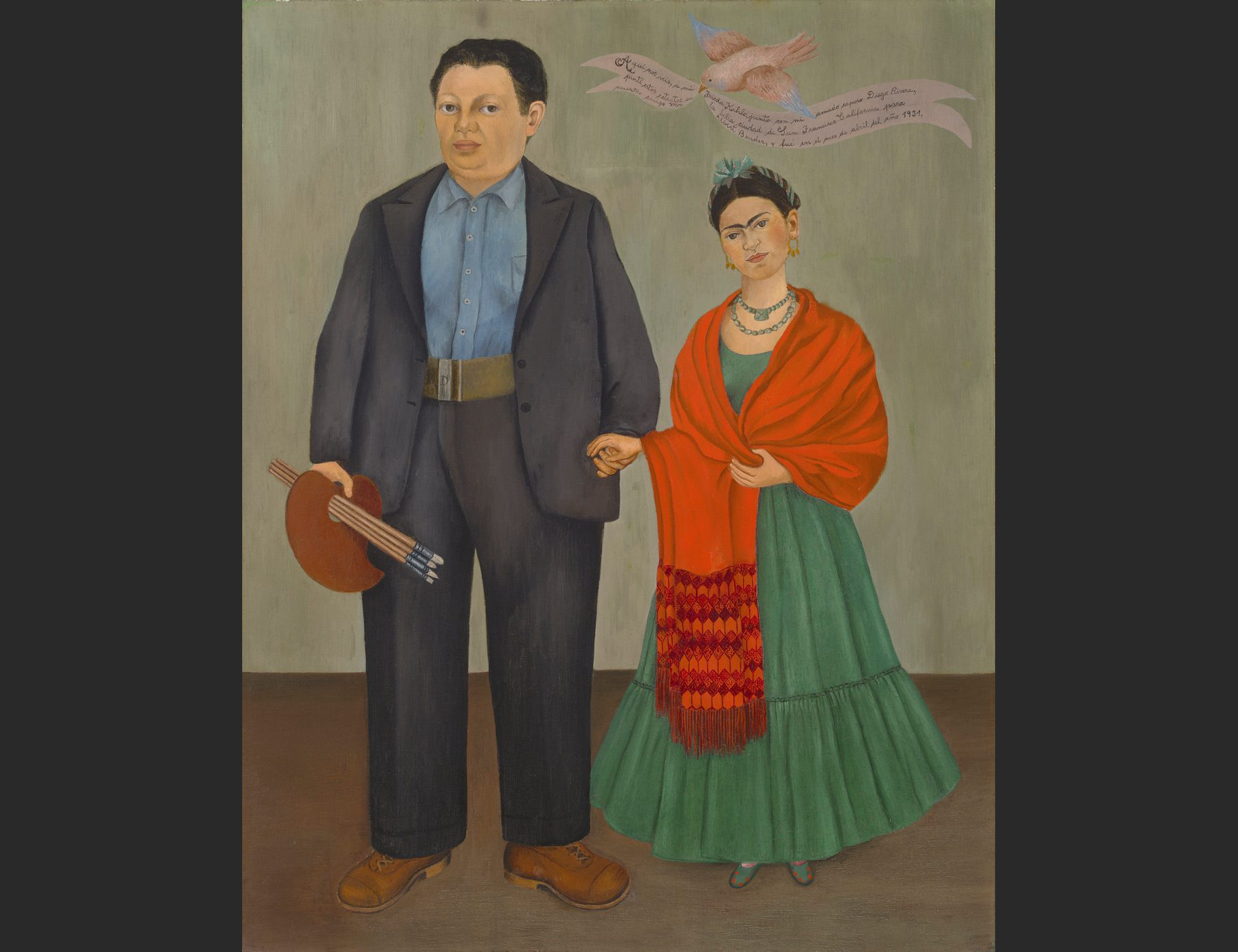

Diego Rivera and his wife are the subjects of Frida Kahlo's "Frieda and Diego Rivera," 1931, oil on canvas, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender. Kahlo painted herself as a more diminutive figure than her husband, who was at the time considered one of the world's greatest artists. (Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Diego Rivera and his wife are the subjects of Frida Kahlo's "Frieda and Diego Rivera," 1931, oil on canvas, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender. Kahlo painted herself as a more diminutive figure than her husband, who was at the time considered one of the world's greatest artists. (Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

ROCKEFELLER COMMISSION

In 1933, Rivera accepted a commission from John D. Rockefeller to paint a fresco in the lobby of Manhattan's Rockefeller Center. All agreed it was to allegorically depict the ultimate choice between communism and capitalism facing mankind. Rivera submitted preliminary sketches and began to work.

On May 1, 1933 — May Day — a small head of Vladimir Lenin appeared in the mural that had not been present in any of the three sketches submitted prior to the work beginning. Rockefeller objected, asking the artist to paint over the face with that of a generic worker; Rivera refused, but offered a compromise. He would add a figure of Abraham Lincoln ("or John Brown, Nat Turner, William Lloyd Garrison or Wendell Phillips and Harriet Beecher Stowe ... ?") to the tableau. Rockefeller cut him a check for $14,000 — two-thirds of the agreed-upon commission — and barred him from the building.

Rivera sought legal advice, hoping to force exhibition of his work under an implied covenant but found little support among the legal community.

"They have no right, this little group of commercial-minded people, to assassinate my work," he said. He offered to redo the work — for free — on any Manhattan wall that would have it. Speaking to a group at Manhattan's Town Hall, he all but admitted he was being devious.

"[T]o prove that my theory would be accepted in an industrial nation where capitalists rule .... I had to come as a spy, in disguise ... ," he said. "Sometimes in times of war a man disguises himself as a tree. My paintings in this country have become increasingly and gradually clearer."

The unfinished "Man at the Crossroads" was painted over and later chipped from the wall. "Diego Rivera's America" has the sketches.

Rivera and Kahlo returned to Mexico; he re-created the fresco, on a smaller scale, in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. He called it "Man, Controller of the Universe."

POOR MAN'S SHIRT

Bruce Springsteen once characterized himself as "a rich man in a poor man's shirt." That seems an apt description of most celebrity communists, including Diego Rivera.

It's difficult to reconcile the radical Rivera with the wealthy painter who took commissions not only from the Rockefellers but from Edsel (son of Henry) Ford and General Motors and churned out dozens of highly saleable easel paintings of children. It's in these paintings that the contradictions inherent in Rivera's philosophy seem to reveal themselves — these are mostly "nice" paintings of large-eyed children not too remote from the high kitsch of Margaret D.H. Keane.

They seem almost devoid of politics, but during a recent preview of the exhibit held for the press, Octavio Sanchez, a Bentonville alderman who grew up in Mexico City near where Rivera and Kahlo lived in separate (close-by) houses, notices that in a painting of two little girls, the lighter-skinned one (modeled by Rivera's daughter) sits on a cushion while the darker-skinned one (modeled by a child of one of his servants) sits on the floor. It's not obvious at first, but there's a distinct class difference.

It isn't as obvious here as it is in some of Rivera's more famous paintings, such as 1935's "The Flower Carrier" or 1928's "Dance in Tehuantepec," but the tension between haves and have-nots is there in the faces of the urchins who posed for the painter, who probably treated them kindly and gave them a few pesos.

Rivera remains one of the artists most people probably know by name and his style is as easily parodied as that of van Gogh and Picasso, who was once thought his peer.

![]() "The Flower Carrier" by Diego Rivera, 1935, oil and tempera on masonite (Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

"The Flower Carrier" by Diego Rivera, 1935, oil and tempera on masonite (Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

BACK IN THE USA

Rivera would return to the United States in 1940, invited back to San Francisco to paint a mural for the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island. For weeks he climbed onto a scaffold to paint as ticket-buying fairgoers watched from behind velvet ropes.

He took as his theme Pan-American unity, attacking it with an ambitious ferocity. The result was problematically gigantic — when the fair closed there was no room in all of San Francisco large enough to accommodate it. (The fresco panels were kept in storage for 20 years — and sustained some damage — before they were installed in the new lobby of the Arts Auditorium of San Francisco City College.)

"One of the biggest challenges for any curator of a Diego Rivera show is how you deal with murals," curator Oles says. There's no real substitute for actually traveling to where the murals are, viewing them in situ.

Oles says Rivera's murals developed from "very simple compositions to increasingly more complex compositions with more figures, and then shifts of scale and then shifts of time and space."

"For me, one of the best ways to understand ... very complicated murals like 'Pan American Unity,' is to understand they're not easel paintings," he says. "They're not single scenes of anything. In fact, even if you just look at this detail, you see it's not enough. It's not an observed reality. It's kind of a montage of different episodes, or objects or people or cultures. Put together on the wall ...

"Rivera really relied on what he learned in Paris ... the Cubists were, of course, very interested in collage. So anybody that's ever done a collage [has done so] by cutting up things from magazines and pasting all down on a piece of paper. It's the same principle here. Images taken from different realities, different spaces, times, places that have been sort of cut out and pasted together to create a new scene that depicts something that no human eye would ever have espied. So that's one thing, the idea of montage. And that's how we can have huge shifts and scale ... . The bridge becomes much smaller than the diver."

It's cinematic, Oles says. Rivera figured out a way to present us with everything, everywhere, all at once. A kind of still movie.

DIEGO, REVISITED

It is tempting to say that Rivera's best work was done before he invaded the U.S, in 1931, that his Mexican paintings feel richer and more vibrant, less inhibited by the demand of his politics. There's a popular notion of Rivera as an ideologue, if not a hypocrite, taking the money of the elites and enjoying a bourgeois lifestyle while producing tendentious, politically charged propaganda.

"Diego Rivera's America" invites a reassessment — if not reversal — of that attitude.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com