TULSA -- A casual fan might wonder why the Bob Dylan Center is in Oklahoma, rather than in, say, Hibbing, Minn., or Manhattan's Greenwich Village or Malibu, where the peripatetic singer-songwriter has kept his principal abode since the mid-1970s when he rented "Adam-12" actor Marty Milner's place.

(Dylan bought his own patch on Point Dume in 1979 for a reported $105,000. It's expanded into a compound with a 6,000-square-foot main structure with a copper dome in a vaguely Russian style as its centerpiece, and more than $1 million worth of handmade tile. Real estate has been very good to Bob.)

Someone who thinks in terms of synergy might see the Bob Dylan Center as a good fit for the city's Arts District, given the other music-theme attractions nearby. Cain's Ballroom, which stands a few blocks away, was originally a garage for the automobiles of one Wyatt Tate Brady, one of the city's founders (about whom we'll hear more later); since 1924 it has been one of the nation's great music venues, with 1,800 seats.

Last year, Leon Russell's old Church Studio received a multimillion-dollar makeover and reopened. It's available for tours, sessions and the occasional concert.

Those a little more versed in the Dylan myth will remember that back in his early fibbing days the young Dylan would sometimes tell people he was an orphan from Oklahoma. (The very first time Robert Zimmerman's alias "Bob Dylan" appears in print, the newspaper reviewer said he was from Gallup, N.M., because Dylan asked the emcee to introduce him that way.) Dylan no doubt picked Oklahoma because of his fascination with (and cannibalistic fetishization of) Okemah native Woody Guthrie.

BECAUSE OF GUTHRIE

Guthrie is one of the reasons the Bob Dylan Center ended up here. Dylan was reportedly so impressed with the Woody Guthrie Center, which opened here in 2013, that he allowed the people behind that museum and archive (the George Kaiser Family Foundation, working with the University of Tulsa) to acquire his archives for a sum The New York Times estimated to be in the $15-million to $20-million range. (His scribbled lyrics to "Like a Rolling Stone," arguably the greatest rock song ever written, sold for a record $2 million at a New York auction in 2014, and the Fender Stratocaster he played when he went "electric" at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival sold for nearly $1 million in 2013.)

George Kaiser, the Oklahoma-born billionaire who is one of the 500 richest people in the world, is the son of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany who emigrated to Oklahoma during the Great Depression. He made his money in oil and gas and later in financial services; he owns more than 60% of the Bank of Oklahoma (BOK) and is part of the ownership group of the Oklahoma City Thunder franchise in the National Basketball Association. According to the Tulsa World, he does not do interviews or attend hotel society gatherings.

He took Bob's papers and books and masters and home movies and cast-off harmonicas back to his hometown and put them up in a charmingly discreet old warehouse cheek-to-cheek with the Guthrie Center. There are 29,000 square feet of exhibition space for the tourists to roam, but the bulk of the material is held off floor, for scholars to poke through by appointment.

The tone is surprisingly humble for a rock star temple -- no Grammys or other awards on display; mainly it's stuff like notebooks (the "Blood on the Tracks" lyrics were written in a tiny crabbed hand in pocket-sized digests). There's the leather jacket Dylan wore at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, near a postcard of apology from Pete Seeger, who protests that he didn't mind Dylan going electric -- it was just that the sound was lousy.

The timed tickets (adult tickets are $15, kids under 17 get in free and dual tickets, which include admission to the Guthrie Center, are $22) allow for a two-hour sojourn, but longer visits can be arranged and might be advised if you're the sort who wants to read every word, watch every film and listen to every recording available.

A lot of the people who might want to visit a Bob Dylan museum might tend to be a little obsessive.

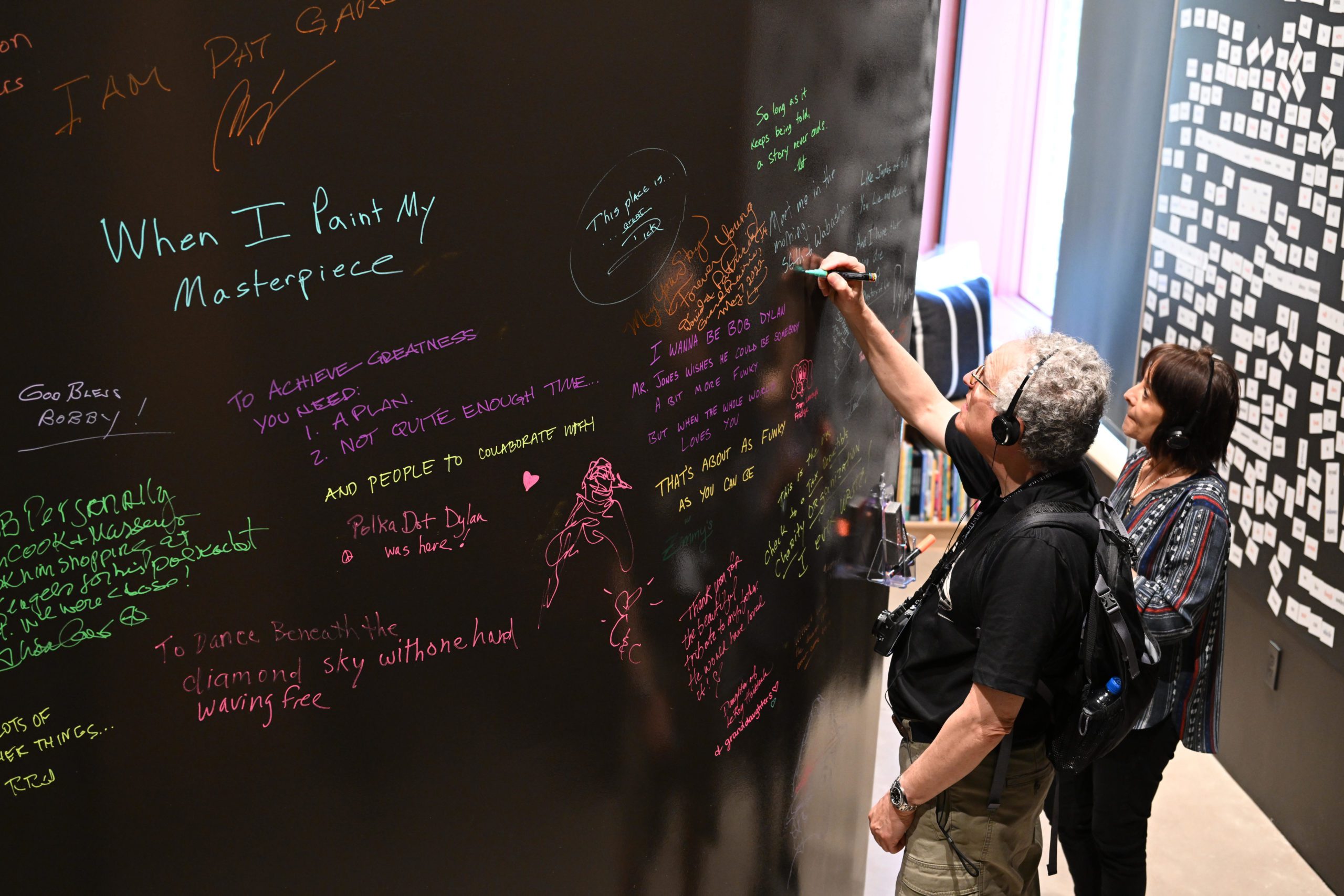

IMMERSIVE EXPERIENCE

It's meant to be an immersive experience, a wash of sounds and light studded here and there with little rabbit holes a visitor can dive down. Two hours go by fast -- if you're the kind to sink into a videotaped conversation between Rosanne Cash and poet Lewis Hyde discussing the nature of creativity and the ways in which gift-giving relates to art-making, or who wants to read all about the relationship between Dylan and a young woman from Mississippi named Ann Hill who, when she died at 25 in 1970, was the oldest living victim of rare muscle disease amytonia (which leaves the afflicted with a lack of muscle tone -- unable to stand or sit upright).

Despite being confined to a wheelchair, Hill graduated at the top of her high school class and managed the largest Elvis Presley fan club in the world, which led to her meeting the singer several times. She appeared in a movie with Danny Thomas and was the first person to graduate from the University of Mississippi via correspondence courses. She learned to type while being fully reclined in bed and wrote for national magazines and the old Memphis Press-Scimitar.

Her connection to Dylan is obscure -- the small exhibit dedicated to her includes a snapshot of her with the singer apparently taken at a Holiday Inn and a letter from her mother to Dylan informing him of Hill's death. (Judging by Dylan's look, I'm guessing the date would be Feb. 9 or 10, 1966 -- Dylan and members of the nascent Band (bassist Rick Danko, pianist Richard Manuel, organist Garth Hudson and drummer Levon Helm, who would leave the tour in November) played Memphis on Feb. 10.

This was a couple of months before the infamous "Royal Albert Hall Concert" -- which actually took place at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. That's the night that someone, possibly a young law student named John Cordwell, who was less upset that Dylan was playing an electric as opposed to acoustic guitar than that the sound was really bad ("It was a wall of mush," Cordwell told a writer for U.K. newspaper The Independent in 2005) yelled out "Judas!" after "Ballad of a Thin Man."

This startled Dylan, who took a beat before yelling back "I don't believe you ... you're a liar!" Dylan then turned to his band and told them to "Play it f*****' loud!"as they lurched into a magnificently aggressive version of the set-closing "Like a Rolling Stone."

Documentarian D.A. Pennebaker's cameras caught that moment, and the clip -- which has become a kind of rock 'n' roll Zapruder film -- can be watched in a theater space in another part of the center. But the Ann Hill story is as incomplete as it is sweet.

"She met you at the motel when you were in Memphis and thought you were wonderful," Hill's mother writes. "Ann thought you were the leading poet of your age ...

"Ann had some poems she wanted you to read when you have time."

It's a touching piece of the mosaic, a window into a brief moment when Dylan was more accessible to mere fans. When he would deign to pose for a photo with a young woman in a wheelchair -- Hill would have been 20 or 21 at the time -- who sought him out before a show. I wish they had put Hill's poems on display.

I think it says something about Dylan that he kept the letter, and the typed-out bio and a clipped newspaper column about Ann Hill. Maybe they tell us as much about the man as the examples of his artwork do -- I think Dylan is a good painter, but a restless one without the patience to work in oils.

A FITTING TRIBUTE

The Bob Dylan Center is the finest museum dedicated to the life and career of a single pop artist (the next-door Guthrie also is the repository for the archives of Phil Ochs, who at one time "Single White Female"-ed Dylan in the same way that Dylan "SWF"-ed Guthrie).

What is its competition? All I can think of is Graceland, which is really more a cult space for true believers than a museum built to tell the more or less truth about a historical figure. The Dylan Center is reverential, but not obnoxiously so.

Still, if you're not interested in Dylan -- or you're skeptical about the worth of his work -- you probably won't read this story, much less visit this handsome and professionally curated space. Through Oct, 15, the center is presenting "Becoming Bob Dylan: Photographs by Ted Russell 1961–1964," a collection of largely unseen images of Dylan taken when he was establishing himself in the Greenwich Village folk music scene.

There are photos of Dylan typing lyrics, hanging out with his girlfriend Suzy Rotolo, strumming an acoustic guitar onstage, receiving an award in the company of James Baldwin in his knit fisherman's cap -- all in lustrous black-and-white tones. He looks like a farm kid come to town. He looks like the myth he invented to both market and protect himself.

The BDC might be a model for this type of tightly focused museum -- it's not hard to imagine a billionaire with the inclination giving Johnny Cash a similar treatment. Elvis Presley could use something more serious than the glorious sui genris roadside attraction that is Graceland. But on the other hand, the spirit of rock 'n' roll is antithetical to the very idea of museums -- you don't want guitars hanging on walls behind glass, you want them in the hands of the irreverent and the bored. The very idea of a rock 'n' roll hall of fame is risible -- authentic rockers should neither seek nor accept that kind of Babbitry.

TULSA, REBORN

But even if the Bob Dylan Center isn't for everyone -- it's apparently not for Bob, who didn't attend the opening and apparently hasn't visited yet -- it's definitely another reason to come to Tulsa, a city that seems to be reconciling itself to its murderous past (the Greenwood District, site of the 1921 race massacre when a prosperous Black neighborhood was burned down by a white mob, is steps away from the Guthrie/Dylan centers).

The street that runs in front of the Dylan Center was originally named for the aforementioned Wyatt Tate Brady, who in addition to being one of the city's founders was an extravagant white supremacist who took an active and unignorable part in the race massacre. So in 2011, under pressure from the community, it was renamed "M.B. Brady Street," pretextually to honor Civil War photographer Matthew Brady (who never set foot in Tulsa). That half-measure was repealed in 2018, and the street became Reconciliation Way. If a spot is open, you can park there for free.

Bob and Woody are a hit. Hey, Tulsa -- now do Leon Russell and J.J. Cale.

Email:

pmartin@adgnewsroom.com