|

|

|

_______ REBECCA DOSS A Memphis native who later called Little Rock home, 18-year-old Doss was described by relatives and co-workers as a friendly, sweet and innocent teenager. Doss had goals of getting her GED and going off to college, with a particular interest in attending Ouachita Baptist University. “She always said ‘I’m not innocent.’ But she was. She was good-hearted and she trusted everyone.” — Melissa Doss, Rebecca Doss' older sister in August 1989 |

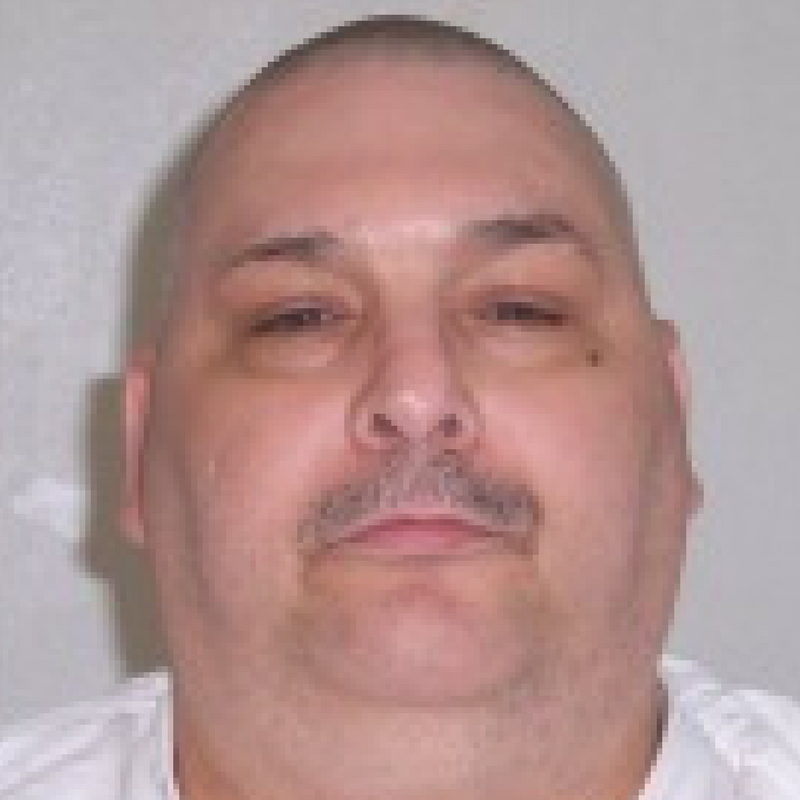

BRUCE WARD

BRUCE WARDFound guilty of killing Rebecca Doss as she worked a late-night shift at a Little Rock gas station in August 1989 Status: Execution stayed Date of original condemnation: Oct. 17, 1990 County in which crime occurred: Pulaski ______ Within an hour of Rebecca Doss' strangulation death, her killer, Bruce Earl Ward, a homeless perfume salesman, was stopped at the gas station where she worked by a Little Rock police officer who had stumbled upon the crime scene. The officer became concerned after finding the Jackpot Inc. convenience store empty and conducted a check of the building, later finding Doss strangled in the men’s restroom with the door key inches away from her outstretched hand. Authorities believe the teen was also sexually assaulted before her death.  Bruce Ward is led out with other prisoners after a mistrial was declared April 10, 1990. “I’m coming; hold on,” Doss replied in the recording, before the tape went eerily silent. A short time after police arrived early Aug. 11, 1989, the officer witnessed Ward walking from the bathrooms on the left side of the gas station on North Rodney Parham Road. Authorities questioned Ward and arrested him as he walked toward his motorcycle. Weeks before the killing, Ward had been selling perfume from a suitcase and living in local homeless shelters. Before that, he had served time in Pennsylvania for the 1977 strangulation of a then-20-year-old woman in Erie, Pa. Doss’ killing was one of two at Little Rock gas stations over a three-week span that summer. Another clerk, a 35-year-old man, was killed in a robbery-turned-slaying July 24, 1989, at a convenience store off Interstate 30. “How can you deal with it? An 18-year-old girl lost her life over absolutely nothing,” David Copeland, co-owner of Jackpot Inc., told an Arkansas Democrat reporter of Doss’ death as he stood feet from the bathroom where the teen’s body was found. An initial attempt to try Ward in the strangulation death ended in a mistrial April 10, 1990. At the end of the third attempt to reach a verdict, a Pulaski County jury found Ward guilty of capital murder Oct. 16, 1990, in Doss’ slaying. He was sentenced to die after 50 minutes of deliberation the following day. The Arkansas Supreme Court later overturned that death sentence as well as another imposed on Ward in March 1993. On Oct. 28, 1997, jurors imposed the death penalty for a third time. The state’s high court upheld that decision in August 2009. Earlier this month, Ward’s attorneys said the convicted killer is severely mentally ill and does not understand the process, adding that his confinement conditions –– living for 26 years in a less than 90-square-foot cell –– have exacerbated his mental instability. Ward has not applied for clemency. |

DON DAVIS

DON DAVISCondemned in the killing of Rogers resident Jane Daniel, who was found shot to death in October 1990 Status: Execution stayed Date of original condemnation: March 6, 1992 County in which crime occurred: Benton ______ At Don Davis' trial for the execution-style killing of Jane Daniel, defense attorneys painted him as someone who “did not have the chances most of us have in life.” On March 6, 1992, a Benton County jury found Davis guilty of capital murder in the Oct. 12, 1990, shooting death of Daniel during a robbery at her home in Rogers. Daniel’s husband, Richard Daniel, found his 62-year-old wife fatally shot in the couple’s basement after he returned home from a two-day business trip.  Convicted murderer Don Davis looks about the courtroom on Tuesday, June 29, 1999, at the Benton County Courthouse. Davis had gone over to the Daniels' home to steal items such as jewelry to make “mad money,” the prosecuting attorney said in his closing arguments. Once inside, Davis forced Daniel through the home and into the basement, where he had her kneel down and shot her in the back of the head. “He got her valuables at the point of a gun,” then-Prosecuting Attorney David Clinger of Bentonville said. “He walked her right past the costume jewelry. He was after the gold.” Testimony during trial showed that Davis had pawned off property in Las Vegas that was believed to have been stolen from Daniel. The stolen property matched items missing from the scene –– a Lucien Piccard watch, an 18-inch strand of cultured pearls and a 35mm Nikon camera. The FBI caught Davis in Albuquerque, N.M., after using pawn shop records to trace his path, said Mike Jones, the head of the Rogers Police Department’s Criminal Investigation Division at the time of the killing. During sentencing, Davis’ attorneys pleaded with jurors to give him life in prison without parole, arguing that he was due leniency based on his upbringing. The convicted killer’s father, Harry Davis of Houston, testified during the murder trial that his son’s mother gained custody after the couple separated. Don Davis’ mother then abandoned her son when he was younger than 1 year old, Harry Davis said. “His mother room-and-boarded him out,” Davis’ father told jurors. In 1994, Davis appealed the ruling, claiming ineffective counsel in his 1992 trial. That appeal was denied in 1999 in Benton County Circuit Court and upheld by the Arkansas Supreme Court. |

_______ JANE DANIEL An Arkansas Gazette obituary described Daniel, 62, as an avid photographer and artist. Daniel was a member of the First Presbyterian Church of Rogers, where she served as an elder and member of the choir. “Usually, in an investigation, you'll find at least someone with something bad to say, but we never found one person that had a bad word to say about her.” — Mike Jones, head of the Rogers Police Department Criminal Investigation Division in 1990 |

|

_______ DEBRA REESE Reese, 26, was a newlywed with a son from a previous marriage, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported. “She told me she was scared, that she didn't know why but she didn't trust him.” — Reese's mother, Katherine Williams, speaking on the call she got Feb. 9, 1993, from her daughter |

LEDELL LEE

LEDELL LEESentenced to death after convicted in the February 1993 beating death of Debra Reese with a tire iron in Jacksonville Scheduled for execution on April 20, 2017 Date of original condemnation: Oct. 16, 1995 County in which crime occurred: Pulaski ______ Debra Reese called her mother, who lived houses away, just minutes after a man came to her house seeking tools for a broken-down vehicle. Reese, who had been home alone while her truck-driver husband traveled to Dallas for a delivery, planned to leave the Jacksonville house after detailing the encounter over the phone the morning of Feb. 9, 1993, but was unable to leave in time, her mother, Katherine Williams, testified. The man convicted in Reese's death, Ledell Lee, returned to the residence minutes later, barged inside and bludgeoned her to death with a tire iron that her husband had given her as a form of protection, prosecutors said.  Ledell Lee in October 1995

Ledell Lee in October 1995

On Oct. 12, 1995, a Pulaski County jury convicted Lee of capital murder in Reese’s killing after two hours of deliberation. Four days later, he was sentenced to death. That trial came a year after a mistrial was declared in October 1994 when a single juror deadlocked the jury. The jury foreman, Bonita Willis Witherspoon, was later convicted of failing to disclose that she had personal connections to the case, including that she had previously been represented by one of Lee’s attorneys. One of Reese’s neighbors told authorities that he had witnessed a man entering her home but stopped just short of calling 911 at the request of his wife, who advised that he not get involved what she believed to be a domestic dispute. The neighbor, who identified Lee in a photo lineup, testified in court that he saw Reese move away from the door, at which point, the man “grabbed that front door and made a beeline inside there, just like, real fast.” Lee was arrested within an hour of Reese's death after some of the cash taken from her wallet was used to pay a bill at a Rent-A-Center store. Defense attorney Bill Simpson argued that Lee's fingerprints were not found on the money. A police witness at Lee's October 1995 trial acknowledged that more than 20 items in the Reeses' home were checked for fingerprints –– none of which were traced back to Lee. Nothing incriminating was found in Lee’s apartment. Lee is also serving time for the rapes of two Jacksonville residents. Prosecutors dropped a capital murder charge against Lee involving another death after the state Supreme Court upheld his death sentence in Reese's killing. |

STACEY JOHNSON

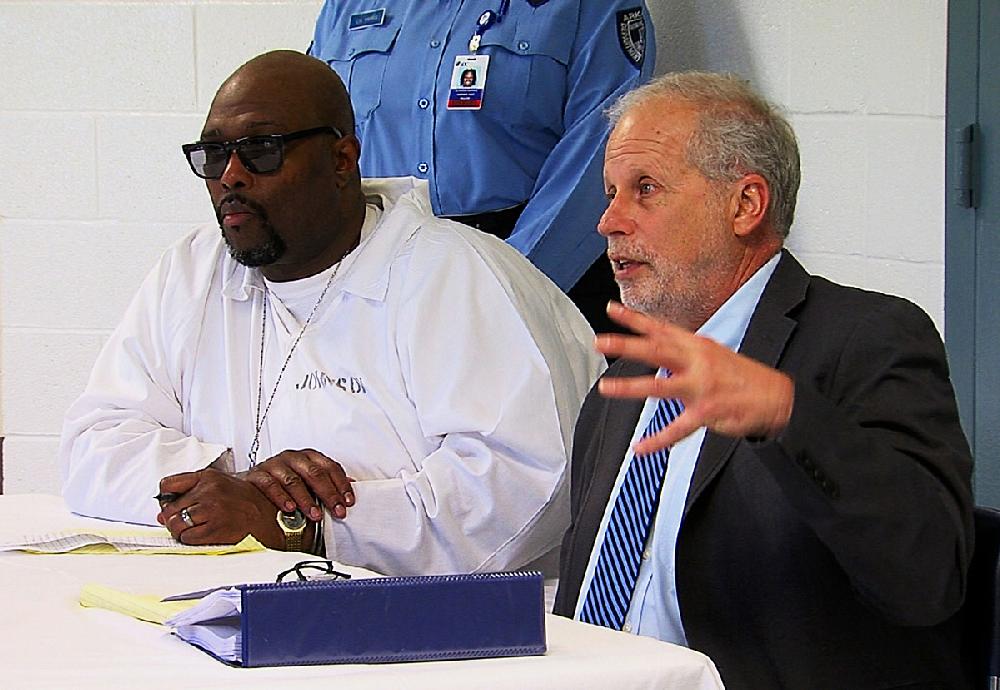

STACEY JOHNSONFound guilty of beating, strangling and killing Carol Heath while her children were in their De Queen home in April 1993 Scheduled for execution on April 20, 2017 Date of original condemnation: Sept. 23, 1994 County in which crime occurred: Sevier ______ When the beaten and strangled body of Carol Heath was found in her De Queen apartment on April 2, 1993, her two children were also found in a bedroom, looking out the window. Heath’s daughter, Ashley, who was 6 at the time, told investigators that a man had come to their door who said he had just been let out of prison. He and her mother started arguing about another man Carol Heath was seeing, the girl said. The man had visited their home a couple times before the day of the killing, she said. The 6-year-old told police that at one point, she and her 2-year-old brother, Jonathan, hid in a closet while the duo fought. The children were in the closet when their mother was killed, which police say was either late April 1 or early the next morning. Carol Heath’s partially nude body was found by a relative in a pool of blood on the living room floor. Heath reportedly had been beaten, strangled and had her throat slit.  Death row inmate Stacey Johnson (left) listens as his attorney Jeff Rosenzweig during a clemency hearing.

Death row inmate Stacey Johnson (left) listens as his attorney Jeff Rosenzweig during a clemency hearing. Johnson was arrested on his way to Albuquerque, N.M., a few months after Heath’s death on a murder warrant during a routine traffic stop. He was convicted by a Sevier County jury of capital murder on Sept. 23, 1994, and sentenced to death, but the conviction was overturned by the Arkansas Supreme Court when justices ruled in 1996 that a police officer should not have been allowed to testify about Ashley Heath picking Johnson out of the lineup. Johnson was retried, convicted and sentenced to death again. He appealed the conviction, arguing he was denied access to Ashley Heath’s psychological examination and treatment records, but the state Supreme Court upheld the conviction in a 2000 decision.  Melissa Cassidy (left) comforts her nephew, Jonathan Erickson, during testimony about death row inmate Stacey Johnson at a parole board hearing.

Melissa Cassidy (left) comforts her nephew, Jonathan Erickson, during testimony about death row inmate Stacey Johnson at a parole board hearing. In the following years, Johnson and his lawyers continued to challenge the ruling through a series of legal battles. In a 2015 clemency request, Johnson’s attorney, Jeff Rosenzweig, brought up issues with submitted evidence in previous trials such as Ashley Heath’s testimony and the refusal to retest DNA evidence. Those outstanding issues raise enough doubt to commute Johnson’s sentence to life without parole, Rosenzweig wrote. At that clemency hearing, Ashley Heath reportedly told the Arkansas Parole Board she did not want Johnson put to death and had forgiven him. At the same hearing, her brother, Jonathan, disagreed. He told officials he could never be truly at peace with the crime if Johnson continued to “have the luxury of life itself.” The state Parole Board again recommended denying Johnson’s request for clemency in March 2017. At the hearing, Johnson said he was sorry for what happened to Carol Heath but maintained his innocence. |

_______ CAROL HEATH Carol Jean Heath was a 25-year-old mother of two living in De Queen with her 6-year-old daughter, Ashley, and 2-year-old son, Jonathan. Johnson stole "a lifetime of memories, hugs and kisses from a mother I loved so very much." — Ashley Heath, Carol Heath’s daughter, in March 2010 |

|

_______ MARY ELIZABETH PHILLIPS Mary Elizabeth Phillips, 35, of Bradford worked at a Bald Knob tax service office and married her high school sweetheart, James Phillips. Together, they had three children and had “a pretty good family going then,” her husband said at a 2007 clemency hearing for Jones. “You need to love your family and understand that they can come and go.” — Lacey Phillips Seal, Mary Phillips’ daughter, at Jones’ 2007 clemency hearing, responding to a question from a television news reporter |

JACK JONES

JACK JONESFound guilty in the death of Mary Phillips, who was beaten, raped and choked with an electrical cord in June 1995 Scheduled for execution on April 24, 2017 Date of original condemnation: April 17, 1996 County in which crime occurred: White ______ Mary Phillips’ body was found in the office of a bookkeeping and accounting firm where she worked on June 6, 1995, after she had been raped, beaten and strangled with an electric coffee-maker cord while her daughter, Lacey, was in the next room. The then-11-year-old, who was also severely beaten, was reportedly at work with her mother because she had a dentist appointment that day. Prosecuting attorneys argued at a 1996 trial that then-31-year-old Jack Jones Jr. had visited Phillips' office twice on the day of her death. The first time, he was looking for work. The second, he returned with a BB pistol, latex gloves and wire. (In later hearings, the attorneys said Jones saw Phillips while painting a sign nearby.)  Lacey Phillips Seal speaks during a clemency hearing for inmate Jack Jones Jr. in Little Rock. When she was 11, Seal survived an attack by Jones in which her mother was killed. Jones later hit Lacey in the head with a BB pistol, causing severe injury, police said. When the charges were read against Jones in June 1995, he reportedly told White County Circuit Court Judge Robert Edwards: "Just go ahead and kill me. Just get it over with.” A jury convicted Jones on April 17, 1996, and sentenced him to death for the murder of Phillips. He was also sentenced to life in prison for the rape of Phillips and to 30 years in prison and a $15,000 fine for the attempted murder of Lacey. Before he was sentenced, Jones apologized to the courtroom, saying, "I'm deeply sorry. If at any time I could give up my life to bring back everything I've taken, I wouldn't even think about it." In 2005, Jones pleaded guilty to another murder in Florida. In May 1991, 32-year-old Lorraine Barrett was found dead in a Fort Lauderdale hotel. The Pennsylvania woman had just arrived in Florida for vacation and met Jones in the hotel's bar. She also was beaten, raped and strangled. Challenges to Jones’ Arkansas conviction in the following years have focused on mitigating evidence as well as the legality of Arkansas’ death penalty laws. Attorney Jeff Rosenzweig argued in a 2007 clemency hearing that jury forms in Jones’ trial had conflicting information. Ambiguities in other cases have been resolved with new sentencing hearings, ordered by the Supreme Court, he said. Rosenzweig also reportedly argued that Jones’ bipolar disorder had not been properly presented to jurors. "None of which excuses what he did, but it does explain it," Rosenzweig said. Jones declined to attend his April 2017 clemency hearing and instead had Rosenzweig read a handwritten letter to the state Parole Board. In the letter, Jones wrote, "I'm sorry, not only for what I did but for you having to come here.” If granted clemency, Jones said, he would decline it. "There's no way in hell I would spend another day or 20 years in this rat hole,” he wrote. Lacey Phillips, now Lacy Phillips Seal, told officials at the hearing she does not want to live another day knowing that Jones is alive. |

MARCEL WILLIAMS

MARCEL WILLIAMSFound guilty of abducting and killing Stacy Rae Errickson as she stopped at a Jacksonville gas station in November 1994 Scheduled for execution on April 24, 2017 Date of original condemnation: Jan. 14, 1997 County in which crime occurred: Pulaski ______ Marcel Williams abducted Stacy Errickson in November 1994 as she stopped at a gas station, later killing her and burying her body near the Arkansas River, prosecutors said. Police said Williams admitted to kidnapping 22-year-old Errickson on Nov. 20, 1994, at a Jacksonville convenience store and forcing her to withdraw money from several ATMs after she left work. He also confessed to raping, beating and choking the mother of two at Riverfront Park in North Little Rock before disposing of her body “where she could not be found.”  Trista Wussick (right) puts her arm around Carolyn Moore after both spoke at a clemency hearing for Marcel Williams, who is scheduled to be put to death April 24 for raping and killing Stacy Errickson. Moore, Errickson’s mother, and Wussick, Errickson’s friend, spoke against clemency for Williams.

Trista Wussick (right) puts her arm around Carolyn Moore after both spoke at a clemency hearing for Marcel Williams, who is scheduled to be put to death April 24 for raping and killing Stacy Errickson. Moore, Errickson’s mother, and Wussick, Errickson’s friend, spoke against clemency for Williams.

Errickson’s hands had been bound behind her back with a cord from her jacket, prosecutors said during Williams’ trial. The mother’s hosiery and lunch cooler were found at a storage facility, and the pickup Errickson was driving at the time of her abduction was later found abandoned at a gas station about 2 miles from one of the ATMs she was forced to stop at that night, authorities said. Three years after Errickson’s killing, Williams was sentenced Jan. 14, 1997, to die by lethal injection. The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported that the jury deliberated for an hour before imposing the death penalty. One juror left the courtroom crying. Before the trial began, Williams had already been serving three life sentences plus 70 years for two other attacks on women around the same time as Errickson’s death. In 1985, Williams, then 15, was convicted of one count of aggravated robbery and six counts of burglary, which carried a 20-year sentence. He had been out on parole since April 1994. |

_______ STACY ERRICKSON Errickson, 22, was a nurse technician at Arkansas Pediatric Facility, according to an obituary that ran Dec. 9, 1994, in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. She was the mother of two young children: a son, Bryan Errickson, and a daughter, Brittany Riley. “Justice has been served. It’s about time.” — Errickson’s twin brother, Tracy Sullivan, on Williams’ death sentence |

|

_______ CECIL BOREN On the Sunday morning he was killed, Boren, a farmer, was doing yard work while his wife was at church. Grady residents called him a pillar of the community of about 500 people. Boren had worked at the Cummins Unit as an assistant warden in the '70s, and he was a retired IRS worker. “He was just good people. This is just a real sad thing.” — Phillip Green, deputy prosecuting attorney of Lincoln County at the time of the killing |

KENNETH WILLIAMS

KENNETH WILLIAMSConvicted of fatally shooting a farmer after escaping from prison in October 1999 Scheduled for execution on April 27, 2017 Date of original condemnation: Aug. 30, 2000 County in which crime occurred: Lincoln ______ Kenneth Williams was already set to spend his life in prison before he shot 57-year-old Cecil Boren to death. The 20-year-old Williams was sentenced to life without parole Sept. 15, 1999, for killing Dominique Hurd, a 19-year-old University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff cheerleader. Williams kidnapped Hurd and her boyfriend, Peter Robertson, from a restaurant, robbed them, then shot them both, Robertson testified. After Williams was convicted, he taunted Hurd’s relatives at his sentencing hearing, saying, “You thought I was going to die, didn’t you?” He spent less than a month in the Cummins Unit before escaping Oct. 3, 1999, in a hog slop tank, a tank used to carry kitchen scraps.  Buddy Boren addresses the Arkansas Parole Board at a clemency hearing in Little Rock. Boren’s brother, Cecil Boren, was killed by Kenneth Williams in September 1999. Williams shot Boren seven times, dressed himself in his clothes and stole his truck, then drove north to Missouri. Authorities caught up with Williams near Urbana, Mo., after he led them on a high-speed chase that ended in a crash with another vehicle. The collision killed Michael Greenwood, 24, a delivery driver. Authorities said Williams spat on the man’s body after the wreck. Within a year of being sentenced for Hurd’s slaying and her boyfriend’s kidnapping, Williams was sentenced to death for Boren’s killing. In addition to the deaths of Hurd, Boren and Greenwood, Williams wrote in a 2005 letter to the Pine Bluff Commercial that he had killed Jerrell Jenkins, 36, of Pine Bluff. Before the killings, Williams had already been incarcerated for much of his life. The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported in 1999 that Williams had spent “more time in prison and youthful-offender facilities” than he had in society. Jefferson County Prosecuting Attorney Stevan Dalrymple told the newspaper that Williams' first criminal act was stealing bicycles at age 8. As a teenager, Williams attacked a guard at a juvenile center and stole his keys. He was released from prison at age 19. At age 20, he robbed and kidnapped Sharon Hence, who was 39 at the time, eight days before he kidnapped and shot Hurd and her boyfriend. |

|

Writing and research: Brandon Riddle, Emma Pettit and Maggie McNeary Design and graphics: Brandon Riddle Photos: Democrat-Gazette file Editors: Jillian Kremer and Gavin Lesnick Sources: Reporting by current and former staff of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette as well as The Associated Press Copyright © 2017, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. |

|