LITTLE ROCK — Earthquakes in central Arkansas may continue for years to come despite the state shutting down natural gas disposal wells believed to be causing the shaking, an official with the Arkansas Geological Survey said.

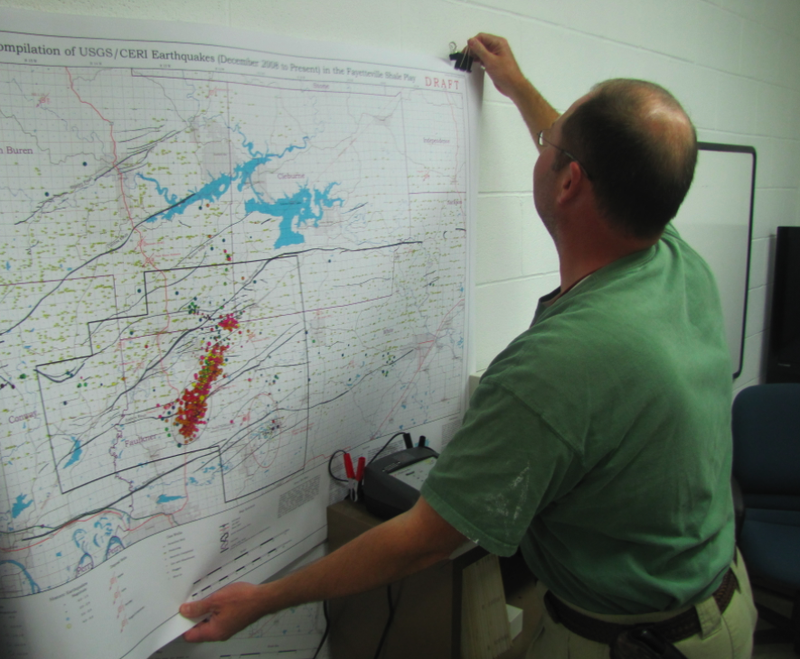

Scott Ausbrooks, the geohazards supervisor for the agency, said natural gas drillers injecting fluid into the ground was the likely trigger for more than 1,300 earthquakes starting in September 2010 in Faulkner County. But even though the wells have been closed, officials expect the tremors to continue.

"No doubt," Ausbrooks said during a recent interview at the survey's Little Rock headquarters. "We expect periodic earthquakes for possibly years to come."

No injuries or serious damage was reported in any of the relatively small quakes, which were largely centered along a previously undiscovered fault line running roughly from Guy to Greenbrier.

But as the shaking continued, the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission heard testimony from Ausbrooks and others about the link between the quakes and the drillers, who use disposal wells to inject pressurized wastewater from hydraulic fracturing into the ground.

The commission ultimately voted in July to create a large moratorium area where future disposal wells would not be allowed and to order four such wells permanently closed.

The results were immediate: The earthquakes tailed off significantly in August and September, with only a handful reported. But then - despite the wells being closed - the quakes started up again in October and November. More than 70 quakes were recorded in that stretch.

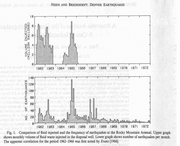

Ausbrooks said that development was not unexpected, because it mirrors what happened at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal in the 1960s. His research into the recent quakes in Arkansas is largely based on earthquakes around that U.S. Army facility in Colorado, which Ausbrooks said geologists have definitively linked to injecting liquid into the ground.

At Rocky Mountain between 1962 and 1966, the volume of liquid injected in a given month correlated very closely with the number of earthquakes in the region. When injection ceased for about a year beginning in 1963, the number of earthquakes declined heavily. When injection started again at even higher volumes in 1964, the quakes surged to record levels.

The injection was stopped permanently in early 1966 and the number of earthquakes again went down significantly. But they continued in smaller bursts of seismic activities through 1972 before finally tailing off completely.

If the same pattern held true in Arkansas, it would explain why earthquakes have continued even after the wells were shuttered.

"Everything we would expect, we've seen," Ausbrooks said. "After the shutdown, we saw a dramatic decrease. And then we've seen periodic bursts, just like they had at Rocky Mountain Arsenal. We expect it go off again and on again. What we hope is we don't have something larger."

In the Rocky Mountain seismic activity, the largest quake of all - a 5.3 magnitude temblor that caused some minor damage - actually came a year and a half after the injection activity stopped, even as the overall number of quakes was significantly down.

It's impossible to predict when earthquake might occur, but Ausbrooks said there are signs a larger quake might be developing in Arkansas.

The temblors in October have been occurring further northeast than the hundreds felt earlier in the year, leaving about a mile-long gap along the fault where no quakes have been centered.

Such gaps are troubling, Ausbrooks said, because they can mean that the pressure is building in advance of a larger incident. A similar-sized gap occurred on the southern end of the Guy-Greenbrier fault and it in February unleashed a 4.7-magnitude quake, the largest of any of the tremors since last September.

"The gap could mean something and it may not mean anything," Ausbrooks said. "We're not here to raise alarm. But it's something we're watching closely."