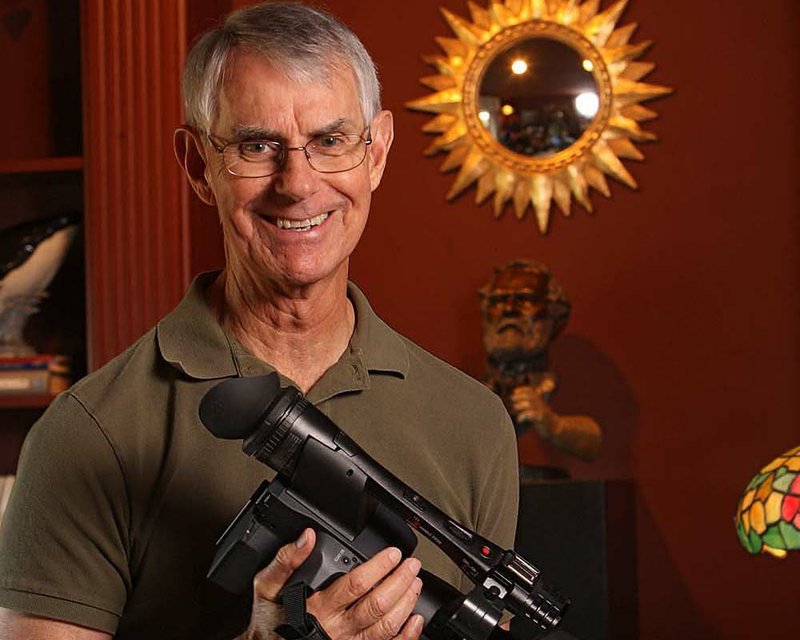

LITTLE ROCK — The biblical saying “Judge not, lest ye be judged” has a new meaning these days for former Judge David Bogard. He’s now on the other side of the judging, at least when it comes to film festivals. After retiring as a circuit judge, he began to live out several of his dreams, including making movies.

Bogard’s short subject Irene debuted on the film festival circuit in 2010. He’s now ready to begin shooting his next film, California Dreaming, a story he wrote about the adventures of a pretty, young, conservative housewife who feels her six-year childless marriage has gone stale. Then she meets a carefree biker.

Over the next month, Bogard will direct the film, mostly on nights and weekends in Maumelle and North Little Rock, where he grew up as the son of Byron Ross Bogard, a lawyer who played a major role in securing the Little Rock Air Force Base for Pulaski County.

Young Bogard graduated from high school in 1955 and went off to Dallas to attend Southern Methodist University. For a time he considered transferring to film school in California, especially since he had an uncle working there in the movie industry. Uncle Johnny introduced him to Lee Marvin and the actors in the television shows Gunsmoke and Adam 12.

“After one idyllic summer school session at Southern Cal, which included getting a tan and sleeping on the beach, and going to Hollywood during the day and jazz clubs at night, I wanted to leave SMU and go to the UCLA Film School,” he says. “Uncle Johnny convinced me to get my business degree, then go to film school. But I never did.”

Returning to SMU, Bogard graduated in 1960 and spent the next sixmonths hitchhiking across Europe, veering from one escapade to another. His most memorable one involved accusations by the Russians of smuggling goods from East Berlin to the western sector. After the Russians scared the wits out of him, he reports, he was allowed to return to West Berlin.

“It was the era when that book Europe on $5 a Day came out,” he says. “I had sold my 1956 Austin-Healey sports car, the most beautiful car ever, which my dad had bought for me when I was in college. I sold that for $1,250 to a crop-duster to finance my trip. I lived off that money for six months by spending 50 cents a day, cooking my own food, drinking water, staying in youth hostels, even sleeping on Omaha Beach.

“I did a lot of photography, but I made the mistake of buying Agfa film in East Germany. When I got home, I took the film to be developed, and for some reason they sent the Agfa rolls back to Germany. When it came back, it was all ruined, overdeveloped. I guess they saw the pictures I had of tanks and stuff and decided they couldn’t send those back to an American.”

Back in the United States, Bogard enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserves, and for a time considered making a career of it, especially after he got a “Dear John” letter from his girlfriend. Instead he opted for a job with Graybar Electric Co. in Dallas, and was transferred to Richmond, Va.

“I had played some trombone when I was at SMU and played in some dance bands, jazz bands and was arranging for the Dallas Symphony,” he says, “so when I went to Virginia, it was one of the best things that ever happened to me. That’s when I really got heavily into music. I sold my trombone and bought a five string banjo and got to Virginia, which was a hotbed of banjo music and old mountain players. I took lessons from a guy named Curly Collins. That’s when we got a group together we took to Georgetown every weekend and played at the Newport [R.I.] Folk Festival.”

In 1964, Bogard shelved his musical instruments for a time to attend law school, starting in Little Rock, then finishing in Fayetteville. He got his degree in 1968 and began practicing law the same year. On the first day of 1981, then-Gov.Bill Clinton appointed him to the sixth division Chancery Court.

One of his first cases led to the overturning of the so called “blue laws,” which prohibited the sale of many items on Sundays.

“I wrote a dissent in a case where Cash Lumber Co. had sued a big chain-type store for selling lumber on Sunday,” he explains. “And the state Supreme Court, which had upheld the law seven times, decided to throw it out. Another case I had was the overturning of the sodomy law.

“But the best thing about being a judge is the juries.If you don’t like people, you don’t have any business being a circuit judge, because the best part is getting to know the people, along with the education you get. You sit there and hear experts on everything, explaining to the jury and me, on how things work. You hear how to perform open-heart surgery, how to birth babies, how to repair gas pumps, how to fix the carburetor on a jet - you name it, you learn it.”

RACKENSACK SOCIETY

Walter Skelton, a central Arkansas lawyer, first met Bogard in law school and has been a friend ever since. He confirms that Bogard has an intense interest in most everything around him.

“I don’t usually trust someone unless I immediately like them, and David was one of those folks I took to right off the bat,” Skelton says. “He knows a lot about a lot of things. I discovered him to be a very able guy, very intelligent, and he approaches everyone with the same openness. He’s so honest, he’s the kind of guy I’d shoot craps with over the phone.”

When he began practicing law, Bogard spent four months in his father’s firm before joining Phil Allen and Jack Young. They were later joined by John Haley and then by Dent Gitchel.

Gitchel recognized a fellow music lover when he met Bogard.

“I was an aspiring guitar player and found out that David played the frailing banjo, and we’ve been friends ever since,” Gitchel says. “David fell in with George Fisher in the Rackensack Society and then he took up blues harp and even had a radio show on KABF. He’s as close as anyone I’ve ever met to being a renaissance man. When he becomes interested in something, he gets passionate about it.

“He had this dream, this obsession, with movies. He’d write screenplays and get his pal, Willie Allen, to go outwith him and shoot scenes. He wrote something and it sold, but nothing ever became of it, so David just kept on being a judge.”

After two years on the chancery bench, Bogard ran for the Sixth Division Circuit Court, winning with 75 percent of the vote. He was subsequently re-elected five times until he retired in 2003, although he sometimes fills in around the state when requested to do so by the state Supreme Court.

He and his first wife, Gail Shoudy, were married from 1968 to 1989 and remain friends. Their son, Stuart Byron Bogard, is an investment counselor with his own company, Providence Assets Management; he is the father of Stuart Byron Bogard Jr., age 4, and Lillian Elizabeth Bogard, age 1.

In 1991, Bogard married Niki Keesee, a colonel in the Army Reserves. She was on active duty in Washington until three months ago, but is now back in central Arkansas working as a team leader at the Little Rock Veterans Center.

POWER LIFTING

Trim and fit at 74, Bogard keeps in shape with power walking and lifting heavy weights.

“I quit smoking in 1987 and started working out,” he says. “I found the best advice in the world in the book Younger Next Year, written for retired people, on how to reverse the biological clock. You run as fast as you can, don’t eat junk and find someone to love. Just sitting around is the worst thing for your body. You can’t stop aging, but you can reverse the deterioration.”

Central Arkansas lawyer Gordon Rather, a longtime Bogard pal, praises his friend’s judicial temperament on the bench, especially when it came to interacting with juries.

“He was always composed and in control of a trial,” Rather says. “He would make jurors proud of their service, some of whom initially had been the type who tried to get out of serving on a jury. David was just honorable, firm and shot full of integrity.

“I took one of my worst beatings in a jury trial in David’s courtroom, and afterward, he put his arm around me and said, ‘If you’re going to try hard cases, you’re going to win some and you’re going to lose some.’ I was feeling pretty low at the time, and that meant a lot to me.”

Rather figures Bogard was always thinking about movies, as he was known for assembling film clips of great scenes in courtroom dramas, including Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird, Paul Newman in The Verdict, Joe Pesci in My Cousin Vinny and Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men.

After retiring from the bench in 2003, Bogard began focusing on what were previously only hobbies, including building computers, model railroading, Civil War research, playing blues harmonica in local venues and filmmaking. His first movie, We Walked the Streets Like Giants, is a documentary about the Blues Patrol, a blues/rock band in central Arkansas in the 1980s.

Gil Franklin, guitarist in the band, recalls meeting then-Judge Bogard at a blues event in the mid-1980s, when the judge came out to a Levy club to hear the Blues Patrol perform. Bogard later became president of the Arkansas Blues Connection, an organization of fans who put on festivals and concerts. Under Bogard’s leadership, the weekly blues jams featured guest spots by Eddie Money, Kevin Bacon, Ted Nugent and Stevie Ray Vaughan, as well as by members of Guns N’ Roses and Little Feat.

“Of all the people I’ve ever met, he’s been the most successful at living a quality life and being interested in a variety of things,” Franklin says. “He’s what I call a true renaissance man. He doesn’t waste any time and is very well organized. You don’t run into people like that very often. He spent about a year working on our film and did a bang-up jobon it.

“I didn’t even know he played banjo until we were doing the film, and then I learned he had spent some time in West Virginia, playing music with Ralph Stanley and even toured with Mama Cass before she was in The Mamas and the Papas. He just loves good music, from the blues to jazz and folk. He’s just a person who’s easy in his skin, as I put it, and I could get in a car and drive 1,500 miles with him and not be afraid of being bored.”

WINNING AWARDS

Doug Williford, an old friend now living in Florida, appeared in an early Bogard film spoof called Conan the Librarian. Williford, a look-alike of Arnold Schwarzenegger, breaks down Bogard’s door in the film.

“I think that film won a prize for special effects, as in the breaking down of the door,” says Williford, president and chief executive officer of a North Little Rock wholesale baking firm, DeWafelbakkers. “I first met David as a plaintiff in his courtroom, when I had a lawsuit against Chenal Country Club. Then we became friends when we ran into each other at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, where we were both watching Wayne Toups and his Zydecajun band.”

“It’s one of the best films I ever made,” Bogard maintains. “He’s collecting overdue booksfor the library, and we dubbed over Arnold’s lines. He comes to the door and we got rid of him, but the door flies open - boom! - and he hit that floor, bounced and came stomping across. We won a special award for blowing that door open.”

More awards came a year ago, when The Courier, a film Bogard had acted in, produced and edited, took home several honors from the audience at the 48 Hours Film Project.

“We had some biker guys come in to act in that one, which was about a delivery guy, a courier, who ducks into a bar and finds himself in trouble, and the bikers, who were real, were just ad-libbing and were really funny.”

Film producer Vince Insalaco has known Bogard for years, dating from when he helped the judge put together his first fundraiser when preparing to run for office. Bogard took two months off from work to help Insalaco make a feature film, War Eagle, Arkansas, in Northwest Arkansas locations.

“He handled all the casting of extras and would make peace between crew members when there was a disagreement,” Insalaco says. “At one point, we were worried about getting a crowd to show up for a ballpark shot, especially since we were running late, past midnight, and we really needed a couple of hundred folks, all dressed in red. Well, we went from no one to a couple of thousand showed up, and David just stood in the middle of the ballfield and took a bow.

“On a more serious note, my wife, Sally Riggs, passed away in 2006, and she had left instructions for David to give the eulogy. We have gone to the same church, First United Methodist, in North Little Rock, and I’ve delighted in watching David teach Sunday School classes, where he would somehow manage to get half the room riled up and the other half laughing. If you want an honest opinion, he will give it to you.”

Gitchel says that Bogard doesn’t put all his time into movies. A huge room in the Bogard basement is filled with a model train collection.

“He’s the darnedest train enthusiast I’ve ever seen,” Gitchel says. “He’s like a fireworks show in the sky going off. Everything he does, he does well. As a judge, he was honest, fair, smart and courteous to everyone who came before him. There was one musician he knew who came before him in court, and David put him in the pen. While he was in there, he got clean, off of drugs, and he now says that David saved his life.”

SELF PORTRAIT David Bogard

DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH Feb. 22, 1937, Little Rock.

MY FAVORITE COURT RULING Led to the end of Arkansas’ “blue laws.”

FIRST MOVIE I RECALL SEEING WAS The Thing (the version in which James Arness played the monster).

THE DOCUMENTARY I AM WORKING ON IS I Didn’t Hear Nobody Pray, about roadside crosses and the stories behind them.

I AM CURRENTLY READING Let Us Build Us a City, by Donald Harington, and Lee the Soldier, letters about Robert E. Lee, compiled by Gary W. Gallagher.

MY FAVORITE CIVIL WAR BATTLEFIELD IN ARKANSAS IS Pea Ridge National Military Park.

MY FAVORITE CD IS Anything, by Moby.

MY FAVORITE BLUES HARMONICA PLAYER IS Lester Butler.

ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS TO DO IS Walk down old railroad rights of way.

A FAVORITE SOUND Is a steam locomotive at night.

ONE WORD TO DESCRIBE ME Dinosaur.

High Profile, Pages 41 on 03/20/2011