LITTLE ROCK — This compilation has become an annual holiday tradition—like homemade eggnog or last year’s fruitcake. Or last-minute Christmas shopping. We’ve rounded up the usual suspects of Interesting Readers and asked the usual question:

What was the best book you read in 2012—and why? It doesn’t have to be new, just new to you. Re-readings don’t count—unless you can make a great case.

Now let’s hop to it. Tomorrow’s Christmas Eve, and there may be a few spots under the tree left to fill, or a stocking that isn’t quite stuffed. And you know you could use the help.

The Dragon Griaule, by Lucius Shephard

This year, The Dragon Griaule was the brightest and most satisfying book I discovered, a collection of six novellas whose narrative hallmarks are clarity, surrealism and a penetrating awareness of human meanness and frailty. Most of the action unfolds in the Central American town of Teocinte, built around (and upon) an immense immobilized dragon, Griaule, whose ill will corrupts the lives of the townspeople. Shepard is far too little known to readers of serious literature: a writer of immense talent and deep, weird, wholly personal vision. You can’t call his fiction compassionate, exactly—he levels too stern a gaze on his characters for that—but if it’s not compassionate, it’s certainly understanding, which is just as valuable an attribute in a writer. His work, it seems to me, is subtle, lyrical and meticulous, and his prose carries a unique glasstipped eloquence—like Faulkner, but with dragons.—Kevin Brockmeier, Little Rock author of seven books of fiction, most recently The Illumination

The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, by Eric Foner

Foner, the premier American Reconstruction era historian, offers a look at Lincoln’s complicated and evolving

attitudes toward slavery. The study nicely complements the portrait of Lincoln in the movie adaption

of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals. Tracing Lincoln’s statements on slavery during his tenure in the Illinois legislature in the 1830s, his one term in Congress in the 1840s, his now famous debates with Stephen Douglass, to the end of the war and passage of the 13th Amendment, Foner gives us the path Lincoln travelled to the point where we see Lincoln in the Spielberg movie. There is one constant in both the periods recounted by Foner and the winding down of the war: Lincoln’s pragmatism and tactical shrewdness. Lincoln was vigilant toward not alienating the four union states where slavery existed. (“I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”)—Nate Coulter, Little Rock attorney

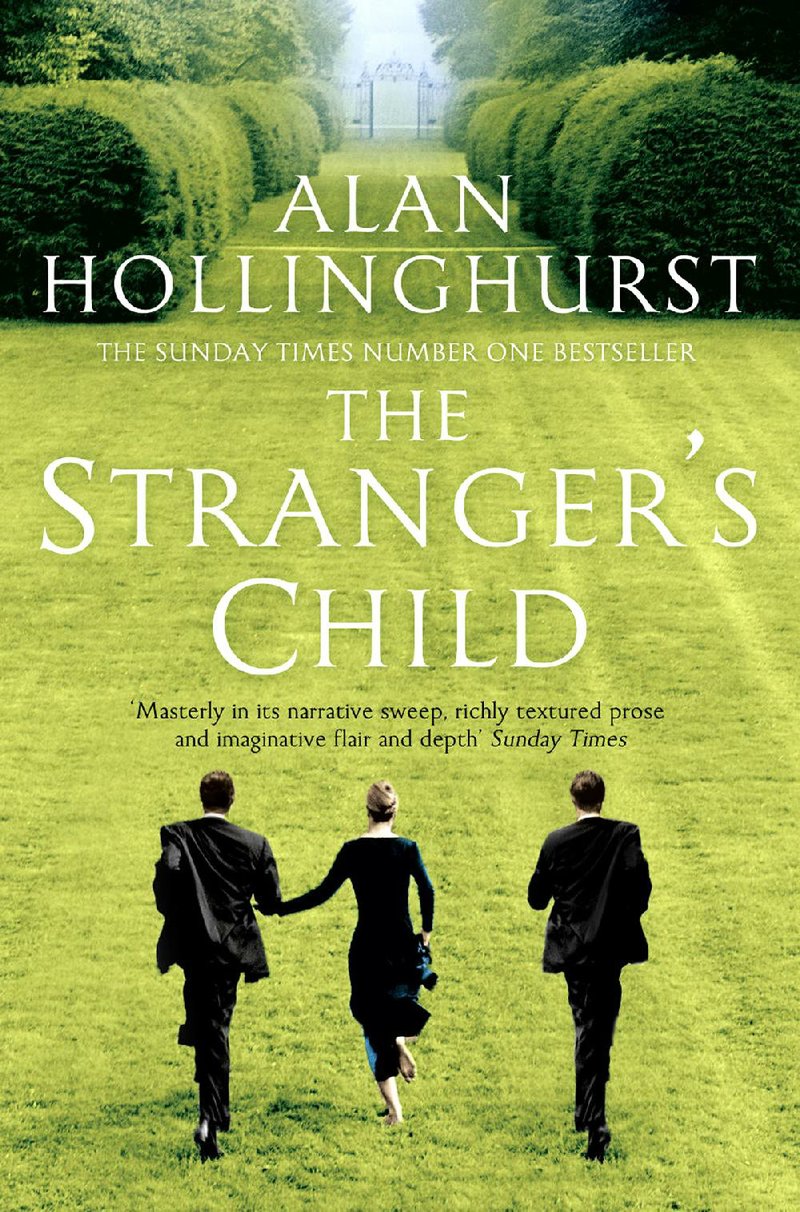

The Stranger’s Child, by Alan Hollinghurst

The last time I tried to explain the plot of this novel, I began to think that suicide might be the only way out. Let hints suffice, then: Georgian England, two Cambridge boys and a younger sister, the most celebrated poem of their era, and a secret. The novel drops in on the secret as it meanders through a succession of lives in the mid 1920s, the late 1960s, the early 1980s, and 2008. The fun isn’t really the secret itself or even its inevitable unraveling. (That happens between sections, with a third of the novel yet to go.) Rather, it’s the curious pleasure of things that age: objects, people, mores, England itself. Granted, as the narrative consciousness of one section gives way to the next, we feel the brutal truth that the rich tapestry of our lives often strikes others as somebody’s crewel work gone wrong. Beautifully written, it’s a novel about memory that celebrates bibelots and chotchkies alike but reminds us, with a wry smile only slightly pained, that neither are remembered for all that long. (Indeed, the last scene takes place in an old house cleaned out for an estate sale and about to be torn down.) By the end, though, we’ve quite warmed to the feeling that that’s just as it should be.—David Strain, chair of humanities and fine arts, University of the Ozarks

A Dance to the Music of Time novel cycle, by Anthony Powell

Anthony Powell was the greatest English novelist of the 20th Century. Once you become accustomed to Powell’s voice, Evelyn Waugh sounds kind of young and Muriel Spark and Kingsley Amis no longer satisfy as they once did. In his 12-volume serial novel A Dance to the Music of Time, we follow our narrator, Nicholas Jenkins, from public school to Oxford to both bohemian and aristocratic London in the 1920s and 1930s (the two worlds overlap more that you would think), winding up with a subtle account of the cultural decay of the early 1970s. Powell proves that first-person novels don’t have to be the narcissistic, soul-searching affairs they so often are. Nick is a highly sociable introvert with an accute sensitivity to character; I do not know who else could give us the moral monster Kenneth Widmerpool, the industrialist Magnus Donners, the spiritualist quack Dr. Trelawney,

the devoted, dog-loving pair Norah Tolbert and Eleanor Walpole-Wilson, the rival poets JG Quiggin and

Mark Members, or the eccentric Lady Molly Jeavons

and her pet monkey, Maisky. There are scores of

characters, and they submerge and reappear

over the decades. A Dance to the Music of Time is a huge novel (12 novels, in fact: A Question of Upbringing, A Buyer’s Market, The Acceptance World, At Lady Molly’s, Casanova’s Chinese Restaurant, The Kindly Ones, The Valley of Bones, The Soldier’s Art, The Military Philosophers, Books Do Furnish a Room, Temporary Kings, and Hearing Secret Harmonies), but it contains a small world, one that reminds me, more than anything, of Arkansas.—Brooke Malloy, development director, Old State House Museum

The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today, by Thomas Ricks

Our army is well-equipped and tactically proficient, but has it been led by competent senior officers? This is the question Thomas Ricks tries to answer. He begins his study with Chief of Staff General George Marshall, who created an excellent cadre of generals in World War II by promoting the most talented officers he could find and eliminating those soldiers who could not do their jobs. After the war Marshall’s methods gave way to a senior officer corps that often accepted mediocrity, rarely fired anyone, and became more concerned with bureaucratic perfection than fighting wars. These structural weaknesses, coupled with a continued failure of high-ranking generals to think strategically, to understand the connection between war and politics, and to adapt to changing circumstances, leave us with an army that is “tactically proficient but strategically inept.” The results of these weaknesses in high-level leadership can be seen in Vietnam, Iraq and now Afghanistan. Ricks, who is one of America’s best military writers, thinks such leaders have failed to adapt to a world where non-state enemies such as terrorists pose a greater threat than conventional armies. Will our army continue to fail us? Yes, he concludes, and as a result more good soldiers will die needlessly in wars that are well-executed tactically but lack any strategic purpose.—Bobby Roberts, director, Central Arkansas Library System

The Housekeeper and the Professor, by Yoko Ogawa

Like many another former reader, I thought I’d lost my taste for fiction. Till a friend sent me this little book that revived it. It’s the first novel in a long time that I can’t wait to get back to all during the day. It’s the prose equivalent of a 19th Century Japanese woodblock print found by Lafcadio Hearn. It is elegant in its simplicity, but not so simple. Like the best algebraic solution. It’s a book about love, but not a love story. It’s about family, but not a family. After a traumatic brain injury, a professor of mathematics is left with only his short-term memory—eighty minutes a day, no more no less. Every day is new to him. He introduces himself to his housekeeper anew every morning. He lives in the awful, wonderful world of the fully present. With only his endless fascination with the natural numbers to give his life order—as this book gives ours in a world full of the crass irrelevancies that fill it to distraction. It is to to be read while sipping green tea to ward off the season’s respiratory demons always waiting to pounce, like the daily news. It is a gift of wonder—and serenity. And the realization that the two go together. —Paul Greenberg, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette editorial page editor

Wish You Were Here, by Grahm Swift

At last Swift has matched the power of his monumental 1983 Waterland. First, Swift moved me with his picture of loss and grief. As the novel opens Swift’s central character, Jack Luxton, has learned that his younger brother Tom has been killed in Iraq. Jack grieves over these losses in recognizably human (and masculine) ways. To top it off, his grief, having reached a high pitch, has just sent his wife storming from the house. This lonely man may be about to lose his last human connection. Second, Swift also got to me with his picture of family life, not only as Jack recalls his lost parents and younger brother but also as he struggles with his fear that his wife is abandoning him in his grief. Third, like Waterland, this novel took me outward from its psychological content to national and global content that intersects with it. Finally, Wish You Were Here tensed me up steadily through its 300 pages. Jack has a shotgun beside him in the opening chapter as he sits by the window waiting for his wife’s return. Will he use it to end his lonely grief? Or will he find another way out of his loneliness?—Terrell Tebbetts, professor of American literature, Lyon College

The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War, by Fred Anderson

The French and Indian War (1754-1763), while largely forgotten by most Americans, was a major precursor to the American Revolution. By removing the French presence from America, the war deprived North American native Americans from an ally they needed to combat Anglo-American settlers who were determined to expand westward. Cash-strapped British officials used the victory to justify new taxes on the colonists. It is during this war that we first learn of a young George Washington as a provincial British officer who benefits from this military experience some 20 years later as he leads the Americans against former British colleagues. And finally, the war caused the colonists to view native Americans as mortal enemies to be exterminated and removed as obstacles to expansion, as many tribes allied with the French. In short, the French and Indian War began the glorious process of our own independence but precipitated our regretful destruction of native Americans’ way of life and culture. Lessons can be learned some 250 years later as our society continues to evolve and transform despite the ironies of progress.—Mark H. Lamberth, commissioner, Arkansas Racing Commission

Bruce, by Peter Ames Carlin

This well-reported biography of rock icon Bruce Springsteen made me think anew about powerfully inevitable multi-generational influence: Everyone has more than a story. All of us have a full saga. In Freehold, N.J., in 1927, the five-year-old sister of twoyear-old Doug Springsteen was on her tricycle when she was run over by a truck and killed. The parents couldn’t cope. They sent Doug to stay with relatives. When they took him back, they were scarred, darkened, remote. Doug grew up into a mess—depressed, beer-washed and unable to hold menial jobs in a dying town. But he was lucky enough to wed a happy woman, Adele, a highly employable secretary. Their first-born was Bruce. Paternal grandparents doted, finding in this new grandson their first fresh start since their little girl died. Adele also doted, wanting to protect her boy from his dad’s darkness. She bought her teenaged boy a guitar that produced racket that Bruce’s dad incessantly cursed.—John Brummett, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette columnist

The Sisters Brothers, by Patrick DeWitt

I read several fine novels this year, but if I had to choose my favorite based purely on the fun I had reading it, The Sisters Brothers would easily win. Shortlisted for the Man Booker prize, DeWitt’s second novel may sound like nothing new in its premise—a couple of hired killers set out after their target in 1850s Oregon and California—but the comic tone of its title promises something different, and the book richly delivers. Its narrator, Charlie Sisters, is a winningly sadsack assassin (much in contrast to his more ruthless brother Eli), and his account of their strange and bloody adventure is by turns hilarious, chilling and (more often than you’d think) surprisingly touching.—Trenton Lee Stewart, Little Rock author of The Mysterious Benedict Society.

The Representation of Business in English Literature, edited by Arthur Pollard

Few writers have “first hand experience of the world of commerce and industry,” Pollard explains in his introduction to these essays. Yet there are many examples in English literature. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe can be read as “a paean of praise to business activity.” Jane Austen’s final and unfinished novel, Sanditron, examines commercial issues. John Galt’s Mr. Cayenne (Annals of the Parish) was “entrepreneur and benefactor.” Charles Dickens’ Little Dorrit is “intensely concerned with business that involves economic transactions, exchanges of labour and goods or services for cash.” Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now features an American perspective on money. Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo, built around a mining operation, presents an analysis of the business-political relationship. H.G. Wells’ Kipps shows the refusal of its central character to “accept the limitations” of his comparable social station, together with “the idea that people are capable of progressing beyond these limits.” Patient investors find arbitrage opportunities in real markets. Patient readers will find nuanced commercial portraits in these novels.—Greg Kaza, executive director, Arkansas Policy Foundation

The Hare with Amber Eyes, by Edmund de Waal and The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, by Michael Chabon

When I looked at my Kindle, these two books leaped out from the list of what I had purchased this past year: The first is historical nonfiction, the other fiction, and they stood out because I read each twice. Both authors are superb writers, and the tales they tell intersect at the time Hitler’s madness darkened Europe, one narrative leading to the shadow of death and the other spurred by it. De Waal, an internationally known ceramicist and a British academic, recounts his two years of research in Paris, Vienna and Odessa in order to understand the 19th and early 20th Century cultural context for a collection of Japanese carvings he inherited from his ancestors, members of a socially prominent, cosmopolitan family that patronized the arts and then vanished from the pages of history in Nazi-occupied Vienna. Chabon’s tale of a young artist trained in Houdini-like escapes begins in Nazi-occupied Prague and turns into a nostalgia-inducing account of the rise and fall of America’s comic book industry. Each book requires slow and careful reading to absorb the illuminating details that build a rich picture of a lost period of time. But each rewards with a deeper understanding of how temporary we are on this earth even if what we have created remains. Ars longa, vita brevis.—Sandra Stotsky, professor of education reform, University of Arkansas

Salvage the Bones, by Jesmyn Ward

Before the publication of her National Book Award-winning novel Salvage the Bones, Jesmyn Ward published a beautiful essay in the Oxford American literary magazine detailing her and her family’s harrowing journey to safety during Hurricane Katrina. Ward’s novel, published several years later, is a study of twelve days pre- and post-Katrina and the effect of these days on the Batistes, a poor African-American family living on the gulf coast of Mississippi. Prominent in the narrative are Esch, the novel’s heroine, who is fifteen and pregnant and still reckoning with the death, seven years earlier, of her mother; China, the pitbull whose image graces the cover of the book, a creature whose fortitude as a mother, companion and fighter prove empowering to the family, especially in the particularly dark days that the novel charts; and Katrina, who, as Ward writes, “left us alive, left us naked and bewildered as wrinkled newborn babies,” a storm that forces them to “learn to crawl . . . to salvage.” This novel was a hit with my graduate students this semester and elicited comparisons to Morrison’s Beloved in terms of its importance to American literary history.—Mary Marotte, professor of English, University of Central Arkansas

Perspective, Pages 75 on 12/23/2012