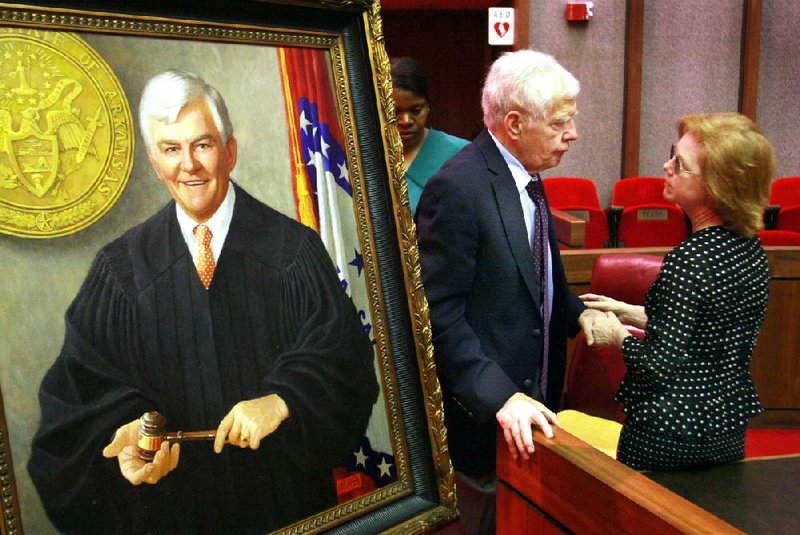

LITTLE ROCK — Tom Glaze, a former Arkansas Supreme Court justice whom law colleagues referred to as fair, dedicated and someone who gave great attention to detail, died Friday at his home in North Little Rock after a lengthy battle with Parkinson’s disease.

He was 74.

Glaze served 30 years on the bench, including 22 on the state’s high court. He was first elected as Pulaski County chancery judge in 1978 before being elected to the Arkansas Court of Appeals in 1980. He served six years on the appellate court before being elected to the Supreme Court.

“Tom Glaze was really a truly dedicated and exceptional jurist during his career,” said former Arkansas Chief Justice Jack Holt Jr., who served with Glaze for eight years on the high court.

“I really feel that his contributions to our legal system and to the administration of justice is really beyond good measure,” Holt said. “At all times, Tom always held true to his beliefs as to what the law was and stood by it.”

As a Supreme Court justice, Glaze was involved in several high-profile cases, including the Lake View School District case in which the Supreme Court ordered the state to overhaul its system for public-school funding.

The high court ended the Lake View case in 2007, the year before Glaze retired, finding that the state had provided an adequate and equal education opportunity for public-school children.

In a 2006 Freedom of Information Act case, Glaze wrote a stinging rebuke of his colleagues after the high court ruled 5-2 that the city of Fort Smith wasn’t required to pay attorney fees to a man who won a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the city.

In a dissenting opinion, Glaze wrote that the decision undermined the purpose of the act. David Harris, a frequent critic of Fort Smith city government at the time, spent $10,000 in legal fees filing the lawsuit.

“Hereafter, only the wealthy or the news media can afford to bring a lawsuit against public officials, who choose, like the city of Fort Smith, to refuse to follow the dictates of the FOIA,” Glaze wrote.

“He was an excellent judge and the state of Arkansas has benefited a lot from his opinions,” said Richard Mays, a Heber Springs attorney who once was a law partner with Glaze in their firm Mays and Glaze. “We have all been affected by his opinions, whether we know it or not. He was one of the best.”

Steve Glaze, one of Glaze’s five children, said that while colleagues remembered his father for being dedicated to spending long hours in courtrooms as either an attorney or a judge, he was also known for his kind nature.

“Truly, I think, what gets overlooked is how he mentored so many people and how he believed that everybody had a purpose, including him,” said the younger Glaze, a lawyer in Washington, D.C. “He really worked with a tremendous number of people in this community to make sure they reached their potential.

“There was a kinder, gentler side of him that many people knew about.”

Before becoming a judge, Tom Glaze worked to clean up voting fraud in Arkansas, a passion that he spent his last years recalling in his memoir Waiting for the Cemetery Vote, published last year. The book recounts his efforts to help stop voting fraud in the 1960s and 1970s in several counties.

Glaze had rewritten state election laws after joining the attorney general’s office in 1967. In 1970, as a privatepractice attorney, he restored the Election Research Council under the new name The Election Laws Institute, which led him to investigate widespread election misconduct in Conway County and later Searcy County.

“Judge Glaze was always tenacious, a tough guy in his studies and as an opponent in the courtroom,” said Jim Wallace, a Little Rock attorney who was a Glaze classmate when both graduated from the University of Arkansas School of Law in 1964. “He was committed to open, fair, honest elections. That was his passion. ... He worked tirelessly for that goal.”

Wallace said Glaze, while on the Supreme Court, once asked his opinion about possibly retiring.

“I asked him if he enjoyed what he was doing and he said yes,” Wallace remembered. “I asked if what he thought he was doing was making a difference and he said yes. I said, ‘Then you need to keep doing it.’

“At the Supreme Court, he worked every weekend writing opinions,” he added. “He was totally committed to that job. He was a great justice on the Supreme Court. I think he has been missed out there since he left the bench.”

Glaze retired from the Supreme Court in September 2008 because of his health, having two years left on an eight-year term. He was first elected to the Supreme Court in 1986 and re-elected twice.

“He lived with Parkinson’s for a long time,” said Mays, who has been friends with Glaze since they met in 1975. “It really didn’t impair his ability to perform his work. In fact, it didn’t impair his mind until its latter stages.”

While on the Supreme Court, Holt said, Glaze wouldn’t shy from taking issue with a court decision and write a dissent.

“They would always be very clear and very concise, as were all of his writings,” Holt recalled. “That was his style.

“I really believe a lot of his good works will remain in the memory of many and, fortunately, in print for many years to come.

“He was truly a great judge.”

Front Section, Pages 1 on 03/31/2012