LOS ANGELES -- The Obama administration's $150 million tax on health insurance for 20,000 dockworkers at West Coast ports is complicating contract negotiations whose failure threatens to shut down 29 ports at a cost of $2 billion a day.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union and its employers represented by the Pacific Maritime Association said they're discussing whether workers, shippers or both should foot the bill for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's 40 percent tax on the most generous health care plans, which takes effect in 2018.

A six-year pact covering ports from San Diego to Bellingham, Wash., expired July 1. The two sides are to resume negotiations Monday to avoid a repeat of a 2002 lockout that lasted 10 days at a cost to the economy of about $1 billion per day. The health care tax is a vexing issue for both the union and management because it may set a precedent, said Nelson Lichtenstein, director of the Center for the Study of Work, Labor and Democracy at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

"The ILWU is really one of the first unions to negotiate this," Lichtenstein said. "It could set a precedent for other workers in other industries if the ILWU has to eat this."

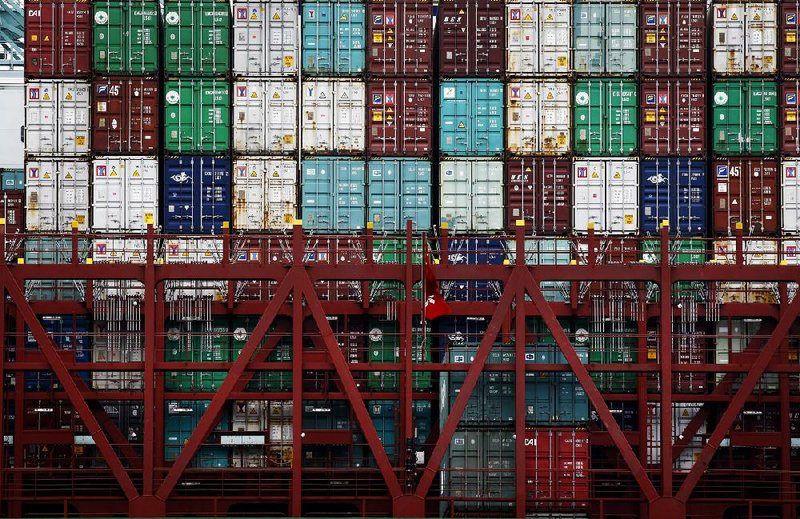

The West Coast ports, which contribute 12.5 percent to the U.S. gross domestic product, have been squeezed by competitors in Mexico, Canada, and the Gulf Coast and East Coast in the U.S., and will be pressured by the opening of a widened Panama Canal in 2015. The West Coast ports' share of U.S. shipping trade volume fell to 43.5 percent in 2013 from 48.6 percent in 2008, according to a maritime association report.

Employers will have to decide whether to reduce health benefits below the threshold to avoid the tax or try to shift the cost to workers, said J.D. Piro, a senior vice president at Aon PLC's Aon Hewitt who heads the consulting firm's health-benefits-practice legal group.

"This will come up in just about every contract negotiation out there," Piro said. "Every employer is going to be calculating when and if they hit the threshold and how they're going to pay for this."

Craig Merrilees, a spokesman for the union, and Wade Gates, a spokesman for the maritime association, both based in San Francisco, called health care a major issue in negotiations. In separate interviews, they declined to spell out their sides' bargaining positions, saying the talks are confidential.

"Nobody's interested in paying the cost," Merrilees said. Dockworkers "feel strongly about the need to maintain their benefits."

The Affordable Care Act imposes a 40 percent excise tax on health insurance plans exceeding $10,200 in benefits for individuals and $27,500 for families, indexed for inflation. Dockworkers, retirees and their families receive fully paid health care valued at more than $40,000 per employee, according to information on the Pacific Maritime Association website. Health care for workers and their families costs $1.6 million per day, according to the association's annual report.

The employers paid $1.4 billion in wages in 2013. They had $1.3 billion more in benefit costs last year, up 244 percent since 2002, according to the annual report.

"The critical issue they are facing is Obamacare," said Jock O'Connell, an international trade economist based in Sacramento. "The dockworkers do enjoy the Cadillac benefits that are subject to taxation under Obamacare."

Merrilees objected to the "Cadillac" label, saying health benefits for longshore workers are comparable "to what most Americans had until recently."

Negotiators have been making progress toward a new contract since talks began in San Francisco in May, Merrilees said. He declined to say whether the agreement would be for six years or less. At a conference in March sponsored by the Journal of Commerce, maritime association President James McKenna speculated that the two sides might reach a three-year deal to postpone a resolution of the health care tax issue, according to the trade publication.

McKenna said the issue was causing employers "a tremendous amount of heartburn," according to the Journal.

Dockworkers have continued loading and unloading cargo since the contract expired, first under an extension of the terms and now without a contract.

The 2002 lockout, which ended when then-President George W. Bush invoked the Taft-Hartley Act to reopen the ports, cost the economy about $1 billion a day, according to the Pacific Maritime Association.

Another shutdown of West Coast ports would put 169,000 people out of work, cost $7.1 billion in lost imports and exports and drain $2.1 billion a day from the U.S. economy, the National Retail Federation and National Association of Manufacturers said in a June report.

Business on 08/02/2014