The Little Rock Police Department has tightened its vehicle-pursuit policy after the number of police chases increased a second-straight year and a pedestrian was killed in 2015.

The revised policy, ordered by Chief Kenton Buckner, states that officers "may be authorized" to chase suspects they reasonably believe have committed or will soon commit "a felony which involves the use or threat of physical force or violence."

The previous policy outlined pursuit tactics and safety measures but allowed officers to begin chases at their discretion under broad circumstances. Police reports show officers mostly chased people suspected of minor offenses, and on many occasions, the department listed "suspicious activity" as the reason for beginning a chase.

"We feel like this [new] policy protects our community better and protects our officers better," Buckner said. "It's very restrictive compared to what we had in the past."

Police departments in Pittsburgh, Milwaukee and Oakland, Calif., are among several agencies that have adopted similar chase protocols in recent years.

Little Rock police supervisors began circulating the new policy Wednesday. The department's 526 sworn officers are required to sign a statement saying they read and understood the protocol, officially known as General Order 302.

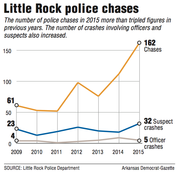

The Police Department recorded 162 chases in 2015, according to data released under the state's Freedom of Information Act. That's higher than the 112 chases logged the previous year and four short of the number of chases recorded in 2009, 2010 and 2011 combined.

The number of chases involving crashes in 2015 increased to 37 from 27 in 2014, the highest total in at least the past seven years. Officers crashed in five of the chases. The pursued vehicles crashed in 32 chases.

One of those crashes left a woman dead and her 18-year-daughter severely injured. Buckner said it led police to re-examine its pursuit protocol.

Trendia Horton, 39, was jogging with her daughter, Nahtali, the afternoon of Sept. 15 when a man fleeing police in a stolen Nissan Maxima lost control of the vehicle, careened onto the sidewalk and struck them both. Trendia Horton was killed. Nahtali Horton was left comatose. She was incapacitated until early December, according to court filings.

A Roland man, Jordan Matthew Vandenberghe, 24, was charged with first-degree murder, first-degree battery and other felony offenses in the case.

The pursuing officer, Zachary Hardman, chased Vandenberghe south on a residential stretch of Chicot Road for less than a mile before the crash, police said. The officer was found to have followed the pursuit policy at the time "to the letter," Buckner said, and was cleared of any wrongdoing.

But members of the Horton family and their neighbors criticized police for chasing a man who had been suspected only of a nonviolent property crime.

Under the new protocol, according to Buckner, there wouldn't have been a chase.

"Yes, we're going to still try to apprehend that person. But if it turns to something where you have a pursuit, and it's for a property crime like a vehicle or something, the risk that we put the public at to retain your vehicle, we just don't feel like that's worth it," he said. "But there are a number of other ways which you can capture people who are stealing a car that doesn't require pursuit."

An international police accreditation group composed of police chiefs, academics and lawmakers also influenced the policy change. Buckner said the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies recently assessed the department and was "deeply concerned" that an agency of its size was averaging a chase every two to three days.

Randy Scott, the commission's Southwest regional program manager, said law enforcement agencies voluntarily adhere to the commission's standards and are evaluated every three years.

He said the commission does not comment on specific agencies, but described accreditation reviews as "strenuous" for departments of all sizes.

"It gives you a chance to take a good look at your own agency," Scott said.

Buckner cited officer safety as another reason for the policy change. More American law enforcement officers have died in vehicle collisions over the past decade than in any other instances, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund.

Little Rock police training division commander Capt. Heath Helton, who analyzes pursuit data for the department, said he had no explanation for the increase in chases in recent years. He said training methods have remained mostly the same; recruits spend 80 hours behind the wheel, about 24 of which involve simulated chases, obstacle courses and emergency maneuvers. Sworn officers complete a refresher course each year as part of the required 40 hours of annual in-service training.

"Defensive driving, that's our primary focus," Helton said.

There had been no major changes to the pursuit protocol in several years.

Helton and his three predecessors in the training division -- Capt. Ken Temple, officer Heath Atkinson and Lt. Marcus Paxton -- each identified "no need for policy modifications" in annual pursuit-analysis reports between 2009 and 2015. They each wrote that they were "unable to find any trends or patterns that would warrant making changes."

An Arkansas Democrat-Gazette analysis of police data found more than one in 1 in 4 police chases during that period involved a crash. The same analysis found that in 2010 and 2011, police listed traffic stops, misdemeanor offenses and "suspicious activity" as the "initial violation" in 62 percent of the 105 chases in those years.

Nonviolent felonies accounted for 21 percent of the chases. Violent felonies accounted for 13 percent.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2011 that fleeing police is a violent felony, but under the new Little Rock police guidelines, "the act of evading or fleeing in a motor vehicle shall not, standing alone, be deemed to be a violent act, crime or felony" that warrants a chase.

There is one exception to that clause: officers may chase a suspect fleeing a residential burglary if the burglar's identity is unknown. But the policy also instructs officer and supervisors to "use any available information to further develop and ascertain the possible identity of the fleeing suspect" to avoid a chase.

"From a property-crimes standpoint, as to why that was an exception, that is probably one of the most egregious, from a victim-feeling-violated standpoint," Buckner said. "It's someone who went into your home. It could be a home invasion, it could just be for property or something. But that is one property crime that we feel the community probably feels that the home should be protected as much as we possibly can."

There were an estimated 2,100 home burglaries last year in Little Rock. Two of them led to police chases, according to the department.

The department's basic pursuit rules remain the same. Officers are required to activate emergency signals and are restricted from ramming other vehicles. Only two officers may be directly involved in a chase. And at all times during a pursuit, officers must consider various environmental factors in determining whether the chase presents a "clear and unreasonable danger" to police or the public.

Unmarked police cars had previously been restricted from chases and traffic stops, but the new policy states unmarked vehicles can be used "only if a marked vehicle is not available."

The policy states that an unmarked vehicle must be equipped with emergency signals, and it will be replaced by a marked vehicle as soon as possible.

Buckner said only experienced officers drive the unmarked vehicles.

"While I understand it may be uncomfortable to someone in the public when an unmarked police car is attempting to pull you over, I trust the professionalism of our seasoned, veteran detectives, and they should have the latitude to be able to do that," he said.

A 2007 study by Prehospital Emergency Care, a medical journal, found that about 323 bystanders were killed each year in police chases between 1982 and 2004.

Trendia Horton was the first bystander killed in a Little Rock police chase in almost three decades, according to the department.

"Any time you have something like that happen," Buckner said, "you have to take a practical look at your policies, at your operation, at our training, to make sure that we're doing everything we can to protect the public and our police officers."

Metro on 03/13/2016