"Save up all your bread and fly Trans Love Airways to San Francisco, USA ..."

-- Eric Burdon, "San Franciscan Nights," released August 1967

My uncle was a sailor; his last port of duty was Treasure Island Naval Station in San Francisco Bay. He liked northern California, so instead of heading home to North Carolina after mustering out he stayed in San Francisco to hang around Lawrence Ferlinghetti's City Lights Bookstore and listen to jazz in North Beach clubs. It was 1962. The Beatles were still in Hamburg. Bob Dylan had moved from Minnesota to Manhattan to look for Woody Guthrie two years before.

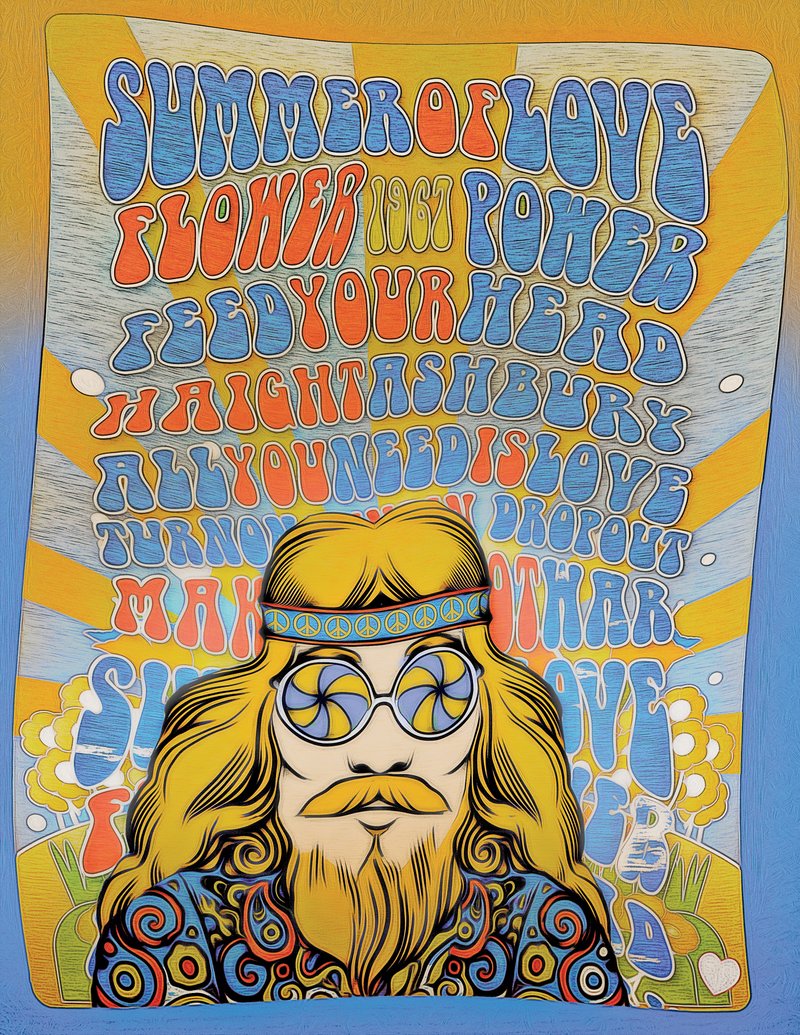

It was five years before the "Summer of Love," a transformative year for American culture.

We can't always say why a community or neighborhood becomes a petri dish for social change, but San Francisco in the early '60s seemed to be especially fertile territory. One of the reasons might have been the American military's aggressive rooting out known and suspected homosexuals from its ranks during World War II -- until 1942 there was no specific regulation barring gays from service. In 1942, military psychiatrists began to classify homosexuality as a "psychopathic personality disorder" that rendered its "sufferers" unfit to fight.

Over the next three years, more than 9,000 members of the armed forces were discharged for homosexuality, a great many of them in San Francisco. A lot of them, like my uncle, decided to stay.

Part of the reason was a pervasive tolerance of libertinism that extended back to San Francisco's earliest days. Established during the 1849 Gold Rush, the red-light district known as the Barbary Coast catered to travelers, sailors, transients and others, with dance halls, gambling houses and brothels where one could pay for a casual encounter with a prostitute of either sex. Gay bars like the Black Cat and Finnocchio's had been openly operating for decades by the time my uncle settled in the city.

Haight-Ashbury, once an upper middle-class suburb of Victorian-era houses (one of the few neighborhoods to emerge unscathed after the 1906 earthquake and fire), was in decline by the late '50s, rents were cheap. Many single family residences were chopped up into boarding houses and apartments inhabited by students at nearby San Francisco State University. By 1963 a strain of Bohemianism unique to the neighborhood had sprung up, a kind of fetishism of the "old-timey." Some young men took to wearing stiff-collared shirts with pins, riding coats and long dusters. They grew their hair long and affected the look of Old West or Victorian dandies.

In 1964, a student protest -- what would become known as the "Free Speech Movement" -- sprang up at the University of California at Berkeley. Students insisted the administration lift a ban of on-campus political activities and acknowledge the students' right to free speech. A series of demonstrations that saw students arrested and jailed eventually led to a new chancellor acceding to student demands. In 1965, Jerry Rubin and others established the Vietnam Day Committee -- a cornerstone of the nascent anti-war movement -- in Berkeley. The same year, the owner of Berkeley's Steppenwolf bar started an alternative newspaper called the Berkeley Barb.

It was about this time that my uncle opened his first antique furniture store in the Haight. (It was more of a junk store; he picked up a lot of his inventory at flea markets and from curbsides.) He sold cheap to the students and others who'd flocked to the neighborhood; he befriended a poet and songwriter named Rod McKuen, who lived on Stanyan Street. He got to know a lot of the musicians who flocked to the area. He sold furniture to the tenants of 710 Ashbury St., Rock Scully and Danny Rifkin, who managed a band called first the Warlocks and later the Grateful Dead.

For a time, the band lived in that house while the Hell's Angels maintained a residence across the street. There's a story about Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, who, beginning in the winter of 1965, started hosting Acid Tests where perhaps 200 people would show up to drop LSD and listen to the Dead play. He once lost his brakes at the top of Ashbury Street and had to choose between crashing into the Dead's house or the Angels'. (He chose the Angels', which maybe should give us pause about the writer's wisdom.)

A group called the Diggers, made up primarily of left-wing actors (Peter Coyote was a member) established pay-what-you-want "free stores" and a free clinic in the Haight; they distributed free food in Golden Gate Park and staged street parades with radical themes like The Death of Money. (The Diggers are often said to have coined the catchphrases "Do your own thing" and "Today is the first day of the rest of your life," which appeared in their pamphlets.)

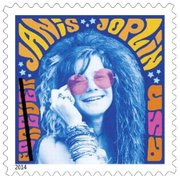

Also in 1966, Janis Joplin returned to San Francisco after her boyfriend broke off their engagement. (Joplin first came to San Francisco in 1963 and lived in North Beach and the Haight. Her friends became alarmed by her methamphetamine use, which had left her emaciated and listless. They bought her a bus ticket back home to Port Arthur, Texas.) She joined a band called Big Brother and the Holding Company.

"She came in and she was dressed like a little Texan," Big Brother guitarist Sam Andrew told blogger John Barthel in 2006. "She didn't look like a hippie, she looked like my mother, who is also from Texas. She sang real well but it wasn't like, 'Oh we're bowled over.' It was probably more like, our sound was really loud. It was probably bowling her over. I am sure we didn't turn down enough for her. ... In other words, we weren't flattened by her and she wasn't flattened by us. ... I mean she was good but she had to learn how to do that. It took her about a year to really learn how to sing with an electric band."

In January 1967, an event called the Human Be-In was held in Golden Gate Park that featured music from local bands including the Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company and Quicksilver Messenger Service. As former Harvard professor Timothy Leary urged the assembled to "turn on, tune in, drop out," old Beats Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder and Lawrence Ferlinghetti looked on approvingly. The Hell's Angels provided security and helped reunite lost children with their parents. Underground chemist Owsley Stanley produced special edition "White Lightning" tabs of LSD for the event, and the Diggers provided 75 20-pound turkeys for free distribution.

On April 15, 1967, about 50,000 people marched in San Francisco as part of the Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (on the other coast, as many as 200,000 marched in Manhattan). About that time, John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas, record producer Lou Adler and publicist Derek Taylor decided to put on a rock concert at the Monterey County Fairgrounds two hours south of the city. In order to promote the show -- which they called the Monterey International Pop Music Festival -- Phillips sat down and, in about 20 minutes, wrote a song for his friend Scott McKenzie to sing.

"If you're going to San Francisco," the lyric went, "be sure to wear some flowers in your hair."

...

This was all tinder for what happened 50 years ago in the summer of 1967 when more than 100,000 young people converged on the Haight, a 25-square-block area in San Francisco. The kids started coming during spring break, and by April, in anticipation of a massive influx of people over the summer, an ad hoc Council for the Summer of Love had formed to "to serve as a central clearing house for theatrical, musical and artistic events, dances, concerts and happenings in the Haight-Ashbury district."

The Haight was the epicenter of what we call the Summer of Love, but it did not contain it. There were satellite events in New York and London. The echoes of that Dionysian spectacle still echo through our culture.

Before the Summer of Love, there were men commuting to work in gray flannel suits and houses with white picket fences. Afterward, psychedelia seeped into advertising, and some barber shops went out of business. There was a sexual revolution and a movement for women's liberation.

It's ironic that McKenzie's hit song "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair)" became synonymous with the Summer of Love because it was written and produced in Los Angeles and bears little resemblance to the psychedelic music that was coming out of San Francisco at the time. It's a pop song which sold millions of copies worldwide, but it's not particularly well-crafted. You could argue that the lyrics are banal, that as a singer, the professionally smooth McKenzie is no Grace Slick.

The Jefferson Airplane was the first San Francisco band signed to a major record label (in 1966); the first to have hit singles and albums. The core was Marty Balin, a former folkie; guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, and guitarist/singer Paul Kantner. They recruited Signe Toly, whose tough female vocals complemented Balin's keening tenor, kind of like a negative image Sonny and Cher. Bob Harvey played bass, and Jerry Poloquin was the drummer. They played at a converted pizza parlor called the Matrix, and their original vein was folk-rock lightly tinged with blues, normal American music for those post-British Invasion times.

By the time they released their first album, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off in 1966 on RCA, they'd fired their first drummer and replaced the serviceable Harvey on bass with the melodic, thunder-fingered Jack Casady (a childhood chum of Kaukonen's). When the album failed to make them rich and famous, Signe made noises about quitting.

They let her and recruited Grace Slick from a band called Great Society, which allegedly was so wretched their ineptitude inspired a recording engineer named Sylvester Stewart to start his own group. (Stewart, after listening to Great Society botch 40 takes before getting through a song, figured that if these idiots were playing gigs, then he might as well give it a shot. His band became Sly and the Family Stone.)

The photogenic Slick brought the band its first hit, "Somebody to Love," written by her brother-in-law, Great Society drummer Darby Slick, and her own "White Rabbit." The songs were Top 10 hits and anchored the band's breakthrough album, 1967's Surrealistic Pillow. She immediately became the band's focal point, not only for the way she looked, but because she was a real singer, with a powerful if limited alto that lent the Airplane a distinctive sound. Balin glided above the rumble of the band, and Kantner -- when he finally stepped up to the mic -- possessed a pleasant, but monochromatic raw croak. But Slick cut straight through the band's roiling weather with a voice like a titanium hatchet. She didn't have the chops that Joplin had, but she could sell the silliest lyrics with absolute conviction.

Which, in retrospect, seems to be what it was all about, doesn't it?

Nobody takes hippies seriously anymore; the word has become the sort of all-purpose obliterator that cartoon third-grader Eric Cartman spits at his friends and uses to dismiss any politician with vaguely progressive ideas.

Nobody talks about levitating the Pentagon or suggests that "love is all you need."

People who weren't there might romanticize the 1960s or take them as a signal symptom of a self-adoring demographic, a generation of entitled cultural bullies who mean to have their music blaring in the nursing home, who will never let the world forget the interesting times through which they lived. But the world resents its history. Every old soldier who insists on talking eventually becomes a bore to those who'd rather text their friends than to try to imagine ancient worlds of unicorns and unironic Beatle boots.

We can still listen to Sly Stone, Jefferson Airplane, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Grateful Dead, the Sons of Champlin or even McKenzie, but we can't hear them fresh. No, there's nothing funny about peace, love and understanding. But it was never all about peace and love and hippie-dippie shamanism. There were jealousies and power struggles. The past is always romantic, but you had to have been there. If you weren't, there are things you cannot know, things The History Channel cannot tell you.

The Haight declined during the '70s but has re-gentrified. These days a 1,300-square-foot condo will run you about $1.3 million, but that's not expensive for San Francisco. A Victorian row house house like the Dead's old place at 710 Ashbury might cost $3.25 million. Real estate website Zillow estimates the Airplane's house at 2400 Fulton -- which is near the Haight but not quite in it -- would sell for about $5.5 million.

So much for the death of money.

I spent part of the summer of 1967 in San Francisco in the care of my uncle, who took me to ballgames and to the Haight, where I saw the hippies dancing. I don't remember much about it; I better remember watching Willie Mays at Candlestick Park.

When I came back to San Francisco the next July, things had changed. Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated; there had been race riots in Washington, Chicago and Baltimore. The Utopian hippie dream had begun to curdle.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 07/09/2017