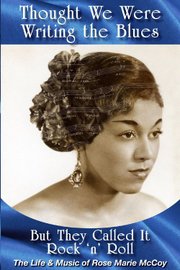

When Arlene Corsano was working on the biography of her friend Oneida-born songwriter Rose Marie McCoy, she would often turn to one of McCoy's songs, "Heart Full of Hope," in times of doubt.

"I used to play it when I was working on something and thinking 'I can't get this done. Who am I to do this,'" says the 71-year-old New Jersey native, before reciting a verse:

I've got a heart full of hope

If I keep on hopin' strong enough

and if I keep on hopin' long enough

my hope might make a lot of sense

I've got that much con-fi-dence

It's just one of more than 800 songs the prolific McCoy wrote that were recorded by the likes of Elvis Presley, Nat "King" Cole, Sarah Vaughan, Ike and Tina Turner, James Brown, fellow Arkansans Little Willie John and Louis Jordan and more than 350 others.

Stephen Koch, Little Rock author of Louis Jordan: Son of Arkansas, Father of R&B, and host of the radio program Arkansongs, first learned of McCoy from hearing Little Willie John's recordings of songs she had co-written with Hot Springs producer Henry Glover.

"One of my favorites is 'Uh-Uh Baby,'" Koch says. "They did 'Letter From My Darling,' which was kind of a hit and 'If I Thought You Needed Me.'"

A song she wrote for Jordan, "If I Had Any Sense I'd Go Back Home," was particularly poignant, Koch says.

"That is a fantastic Louis Jordan song," he says. "After he left [recording label] Decca it was a great, overlooked song. It was a major song at a time when Louis Jordan needed that."

Her song "Trying to Get to You," which showed up on Elvis Presley's self-titled 1956 album, was supposedly a favorite of Presley's mother.

"I know he liked it because he sang it with feeling," says Corsano, the retired teacher and author of 2014's self-published Thought We Were Writing the Blues but They Called It Rock 'n' Roll: The Life and Music of Rose Marie McCoy. "And when he did it in his 1968 television special, he really put his heart in it."

Corsano was in town for last month's 25th anniversary celebration of the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame, into which McCoy, who died of pneumonia in 2015 at 92, was inducted in 2008.

"It was a big show," Corsano says of that 2008 ceremony. "Rose sang. She was such a good entertainer. Everybody was excited to see her."

Al Bell, the Brinkley native and former president of Stax Records and past president of Motown Records Group who spoke at McCoy's induction, has said of her influence, "I don't know of any other songwriter with the kind of track record Rose Marie McCoy has. Her songs have been recorded by so many legendary artists in such a diversity of styles: blues, jazz, rock, rhythm and blues, country, pop, gospel. It's mind-boggling what she has done."

A long way from the "tin top shack" McCoy grew up in with her family in the tiny Phillips County farming community of Oneida.

. . .

She was born Marie Hinton on April 19, 1922, the youngest of Celitia and Levi Hinton's three children. Her father was a farmer and she and sister Alberta and half-brother Johnny worked with him on their 40-acre farm to scratch out a living.

She sang and played piano in church -- Mom was a Baptist, Dad was a Methodist -- and remembered hearing a farmhand singing blues while he worked. She would sneak away to sit in a car owned by her uncle and kept in a barn near her house to listen to the radio, but only briefly for fear of the battery going dead.

When it was time for high school, McCoy moved to Helena, the Phillips County seat, to live with her grandparents and attend Eliza Miller High School. In downtown Helena, she would stand outside a club to hear the blues. She also learned to stand her ground with the children who teased her for being from the country.

"She was beautiful," Corsano says. "And she loved clothes. In high school, some girl once said, 'You never have anything new, do you?' A lot of it came from that. She was always dressed really nice."

And she had started writing, little poems and tunes, mostly, that she never showed anyone.

. . .

After high school, McCoy returned to Oneida to work on the farm. When she was 18, she legally added Rose to her name and, after spending a year back home, left for a job cleaning and baby-sitting for a family in the Catskill Mountains. When a job offer to keep house in the Bronx came, she jumped on it and moved to New York.

She moved to Harlem in 1942 and was a regular in the audience at the Apollo Theater. It was around this time that she started singing in clubs and was spotted by a scout who introduced her to booking agents, finding her work in New Jersey clubs.

On a trip to visit her sister in Memphis in 1943, McCoy ran into an old flame from Helena, James McCoy, who was serving in the Army. Three days later they were married, and a few days after that he was on a ship to Germany as World War II raged. She returned to New York and got an apartment in the Bronx, working as a welder in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and singing in nightclubs as a side hustle.

The first Rose Marie McCoy-penned recording came not long after the war ended and James returned home. McCoy had been singing with a group called the Dixieaires and taught them her composition "After All." She left the group, though, and they recorded it with singer Muriel Gaines. Her meager earnings for the song -- a single $8 royalty check -- wasn't much incentive to keep writing, but she persisted.

. . .

She spent the late '40s and early '50s singing and touring the northeast and Midwest. In 1952, she recorded two of her songs, "Cheating Blues" and "Georgie Boy Blues" for the Wheeler Records label, though neither was a hit for the short-lived imprint.

Her first taste of chart success would come from a 1953 duet with blues belter Big Maybelle. "Gabbin' Blues" was a McCoy original written as a put-down, "dozens" style, call-and-response song. Maybelle would sing a line and McCoy would come back with an insult. The track hit No. 3 on Billboard's R&B charts. Big Maybelle would appear in the Top 10 again that year with McCoy's "Way Back Home."

It was also in 1953 that she began working with writer Charlie Singleton, who would later be known for co-writing hits like "Strangers in the Night" and "Spanish Eyes," among others. It proved a fruitful relationship.

Between 1954-'56, the duo penned seven Top 10s for Big Joe Turner, Faye Adams, Nappy Brown and others.

"She learned a lot from Charlie," Corsano says. "He was older than her and he knew the business could be shady. He taught her to get the money and not sign over her rights to songs."

They would meet at a New York restaurant called Beefsteak Charlie's, Corsano says, and "would write in the mornings and in the afternoon would go to the song publishers."

While McCoy, who played piano and guitar, never learned to write music charts, she would write down lyrics and work with her voice to find a melody and often used someone else to write the music on lead sheets.

By 1955 she and James, who worked for Ford Motor Co., had a Teaneck, N.J., home, a green Cadillac and a small yacht. She returned to Oneida almost yearly when her parents were alive, and though their marriage was rocky, she and James stayed married until his death in 1999.

She and Singleton, who died in 1985 and to whom Corsano's book is dedicated, worked together six years and then went their separate ways. Presley recorded her "I Beg of You" in 1957, Ike and Tina Turner recorded "It's Gonna Work Out Fine" in 1961 and she wrote and produced five songs on Sarah Vaughan's 1974 album Send in the Clowns.

"She was always writing," Corsano says. One of McCoy's last projects was writing with country singer Billy Joe Conor, who included some of their songs on his self-titled 2013 album.

"I think this is the mark of a great songwriter," Koch begins, "you don't hear it and think, 'That's a Rose Marie McCoy song.' That's part of why she was so good. I think she skews toward the blues side of R&B, but she had her fingers in so many things."

While there were some women writing in the early days of popular music and R&B, there weren't many, and writers such as McCoy, Sue Sandler and others paved the way for the likes of Carole King, Sylvia Moy, Valerie Simpson, Diane Warren and current pop stars like Rihanna and Taylor Swift.

"There were lots of things she wouldn't talk about," says Corsano, who first met McCoy in 2001 at a party at the Teaneck home of singer Maxine Brown. "I'd ask, 'Was it tough being a woman?' And she'd say, 'Ahhh, I did what I did and it worked out.'"

Corsano, who published her book just two months before McCoy died ("I would have been devastated if she hadn't seen it," she says), is working on a musical based on McCoy's life called Write on, Rose.

"It's all Rose's songs," she says. "It's her story. She loved talking about [her life] and I loved listening. It was, like, wow, Johnny Mathis? You kissed Jackie Wilson! And here she was, a big writer. She taught me to dream big and never give up."

Style on 11/12/2017