Faithful Reader will remember the exciting week in June 2017 when Old News discovered the existence of Henry "Heinie" Loesch in the archives of the Arkansas Gazette.

Oh, what a discovery that was, and how thrilling to share news of an Arkansas Gazette icon who, by the way, was not in fact forgotten by living Arkansans who knew the man.

While sometimes I like to fantasize that Friendly Reader might be as ill-informed as I am and so doesn't notice the ignorance behind my enthusiasm, more often I have to imagine historians marking up these columns in red pen on Monday afternoons, and snickering. Some weeks it is all too evident that all I know is what I read in the newspaper.

My excuse for not already knowing about Heinie Loesch is that 100 years ago, few newspaper articles included reporters' bylines. And so the digging it took to figure out his name felt like opening Tut's tomb. I wore an exclamation point as a hat for days and bored co-workers with my thrilling Heinie.

It was impossible not to sense the talent behind the gruff humor. Newsprint does catch and hold voices, and as you read slowly through days, weeks and years, you recognize certain ones. You almost hear them. Young Heinie Loesch had a lovably combative voice.

[RELATED: Freshly “fired” from WWI, an ex-corporal laughs about his four months at Camp Pike]

From newspaper reports of men called by the draft board, we know he was classified A-1 in July 1918 and ordered to report for examination that August.

The very nearly 3,500-word letter I have abridged for this week's Style cover raises many questions I am mostly unable to answer. For example, it suggests he was quarantined longer than the usual 10 days as an incoming trainee, and yet was made to scrub floors in the hospital ward. Did he come in with a cold?

And when, as he says, he rejoined his company, were they housed near the Infantry Central Officers Training School drill ground or was that field the view from the office in which he worked? I've squinted at several maps of Camp Pike while trying to deduce what buildings met his description of North Avenue but am simply not informed enough to know. If Helpful Reader can tell us more about Camp Pike, please share.

From his description of the one older noncommissioned officer he worked with who planned to insult anybody who asked what he did in the Great War, I deduced that Loesch served at 162nd Depot brigade headquarters, with Remington No. 10 typewriters. But that's merely my thought. I wasn't able to access his military record other than the draft registration cards by my deadline, in part because it didn't occur to me to try that until, yes, my deadline. The other part of my failure was not being his relative.

The young ex-corporal who wrote the letter had not yet married. He did that 11 days later.

And he had not yet nicknamed the 1919 Russellville Aggies "Wonder Boys" — a nickname that stuck even after the school became Arkansas Tech.

He did not have children. And he did not leave Arkansas for bigger jobs in more popular states.

After his four months of active duty Loesch returned to the Gazette for another 33 years, 15 of them as "sporting editor" — a one-man sports department. Later he was a tough news editor, meaning he harangued reporters about their overuse of adjectives, any use of exclamation points and other offenses against decency, and he also likely drew up pages and ran the copy desk.

Oral histories of his co-workers that are maintained by the University of Arkansas' Pryor Center (pryorcenter.uark.edu) and a few books about the Gazette depict an old man in a green eyeshade who sat upon a box or keg — until it was spirited away in the late 1940s and replaced by a chair. He is said to have teared up over the disappearance of that keg.

Knowing as we do that in 1951 heart trouble forced him to retire, my heart aches for the sense of impending loss that keg would have embodied for him.

In his oral history, former staff member Farris Wood recalls that a year or two after his stroke, Loesch tried to return to the newsroom. "I could, to this day, go over and cry, thinking about him trying to gut his way through that night. He didn't have it," Wood says. "He was so broken physically, and he was shaking all over."

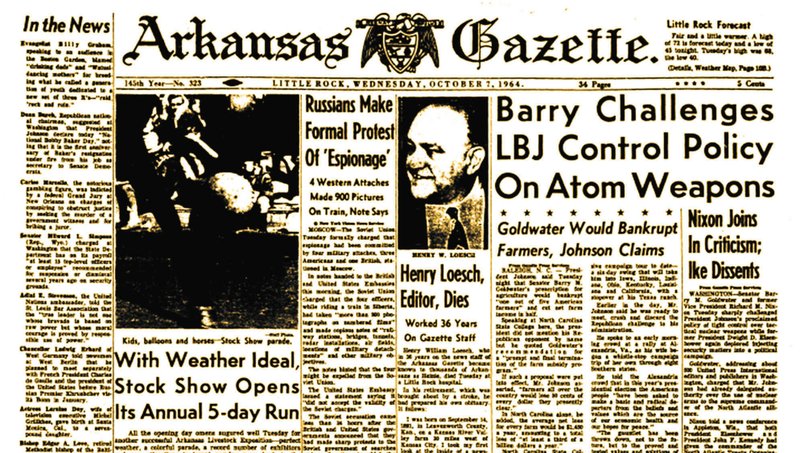

When he died in 1964, the Gazette published the obituary he wrote for himself, on the front page. I've shared bits of it before (June 12, 2017), but they are good enough to repeat:

I never was given any medals or citations. I was just one of the hired hands who assembled late every afternoon at 112 West Third Street to do a night's work. I never established any claim to fame and now that I will be returning to dust I only hope there is someone left to say at least 'He tried.'"

In an editorial tribute after his death, the Gazette said, "For the place he made for himself, and for his fine, sincere character, he will be long remembered."

Let this be true for Heinie Loesch — and for the other gifted, language-loving people who passed through city newsrooms entertaining us and collecting good information for the good of Arkansas. Let us all hold on to their names and some notion of their effort, or failing that, at least let me hold on to the idea that I really ought to try.

Email:

cstorey@arkansasonline.com

Style on 12/24/2018