HARTFORD -- After more than a century, the schools will close for good in this Sebastian County town at the end of the spring semester.

But it won't be the death knell for Hartford, said the Rev. Eddie Kazy of Abundant Life Fellowship.

"You take the bullet," said Kazy, who is also a member of the Hartford City Council. "It's a wound, but it's not a death. Hartford will lose some population, but the town will survive."

Hartford has a history of surviving.

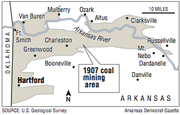

Located 5 miles from the Oklahoma border, in a valley between the Sugar Loaf and Poteau mountains, Hartford was a coal-mining boomtown in the 1910s with a peak population of about 4,000, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture.

Back then, Hartford had four banks, a hospital, eight doctors, two dentists, three drugstores, two hotels, two movie theaters, several restaurants and saloons, and nine churches, according to the encyclopedia article.

An eight-room, brick school building was completed in 1910, serving all 12 grades.

Hartford was soon a center for gospel music publishing. By 1931, the Hartford Music Co. was one of Arkansas' largest publishing companies, printing and distributing more than 100,000 books of music a year, according to the Arkansas encyclopedia. "I'll Fly Away," one of the most recorded gospel songs, was published by Hartford Music Co. in 1932.

Sixteen coal mines operated within 7 miles of Hartford. Three of those mines were within the city limits.

Hartford drew national attention in 1914 when owners of one mine tried to operate it as an "open shop," and the United Mine Workers of America went on strike.

President Woodrow Wilson sent a squadron of the 5th Cavalry from Chicago to "Hartford Valley" to keep order and disperse "riotous assemblages" during the strike, according to an article in The New York Times. Seven defendants pleaded guilty the following January to charges of conspiracy against the government.

As coal gave way to oil and gas, the mines closed and the population of Hartford declined rapidly -- down to 1,210 by 1930.

The publishing industry left, too, when Albert Brumley purchased the Hartford Music Co. in 1948 and moved it to Missouri.

When the last census was taken in 2010, Hartford had a population of 642.

On a recent weekday afternoon, nothing was open downtown except for Hartford's one store, Hugs & Biscuits No. 3.

American flags flew all over town, and billboards proclaimed "Jesus is Lord."

The only traffic going down Broadway Street was a boy on a skateboard.

Ellis Johnston, a Hartford mechanic, said he's seen ominous signs since the school closure was announced Jan. 9.

"I've already seen countless loads of furniture leaving town," Johnston said Monday.

The Hackett School Board announced that it was no longer economically feasible to keep operating the campus 15 miles to the south in Hartford.

Superintendent Eddie Ray said the school district is in the red because of an overall decline in enrollment. He said the Hartford campus, which has an elementary and high school, has about 228 students. There are about 585 students on the Hackett campus.

The Hartford School District was annexed into the Hackett district July 1, 2015.

"The primary condition to Hackett accepting Hartford into the district was that it remain financially sustainable for the district," Ray said. "Hartford's enrollment has been in sharp decline in 12 of the previous 13 years."

He said the district will have to use about $350,000 of its savings this year to make ends meet.

"Our district student population by grade may require two teachers, but we are forced to have three because of maintaining two campuses," Ray said. "We have a principal, media specialist, counselor and other staff members that aren't serving very many students. After all factors are considered, the only way to increase efficiency so that we improve our legal balance enough was to close the campus."

Some people in Hartford are taking it hard.

Mickey Burns posted on the "Hartford, Arkansas 72938" Facebook page that her daughter, Winter Rose, will be in the last graduating class of Hartford High. "It breaks my heart -- her class picture will not be hanging in the cafeteria! Her grandfather and father's senior pictures hang on those walls."

Rose said she has mixed feelings about being in Hartford's last graduating class.

"I feel honored about it, but yet upset at the same time because it's been my school since kindergarten and the fact other students won't get to experience receiving a diploma with Hartford High School on it," she said.

Rose said the students don't know yet where their class composites will be displayed.

David Lee, principal at Hartford schools, said school officials are working with the W.J. Hamilton Memorial Museum in Hartford and exploring other options regarding memorabilia like photos and sports trophies so they will stay in the community and be accessible.

Hartford is home of the Hustlers, but their mascot is the beaver.

"The explanation I have heard was that back in the '30s, Hartford's football team played a large school in our area and beat them," Lee said. "The newspaper article about the game said the Hartford players hustled like a pack of beavers, and thus the name hustlers and the mascot."

According to the Hartford School's website, hartfordhustlers.net, Hartford was the first school in Arkansas with a lighted football field. But Hartford stopped fielding a football team after the 2014 season.

"One of the stipulations for Hackett to agree to the annexation was that Hartford had to drop football," Ray said. "The Hartford School Board agreed to that stipulation when they agreed to the annexation. They were struggling to field a team each year and to maintain enough numbers to maintain a team during the season for a few years prior to the annexation."

Sherry Barnes said her father played football for Hartford High School in the early 1930s. After school, he would walk several miles to a mine for work. Then he would walk back to the school for football practice or games.

Before the lights were installed, they "painted the football in some kind of banana paint," Barnes said.

"It smelled like bananas, but it made the football glow at night," she said.

Barnes is a 1969 graduate of Hartford High School who taught business education there for 25 years. She is publisher of the Hartland Heritage, a fortnightly local newspaper, and chairman of the Hartford Gospel Music "Hills of Fame" Songfest, which is held every year on Mother's Day at Faith Chapel.

Mayor Roy Shankle said the school is the heart of Hartford.

"They've been telling us for 10 years, but you always hold out hope that it's not going to happen," he said of warnings of the impending school closure.

Shankle said students in Hartford also have the option of going to school in the nearby cities of Greenwood or Mansfield.

Shankle said some retired teachers are spearheading an effort to start a charter school in Hartford, but even if that effort is successful, the charter school would have only a few students its first year.

He described the charter school effort as the "little spot of light at end of the tunnel."

Some families will probably move to Hackett so they'll be closer to the school their kids will attend in the fall, Shankle said.

"We're going to lose some of them whether we want to or not," he said of those families.

Barnes was enthusiastic about the possibility of a charter school.

"Our charter school is going to be fantastic when we get this thing going," she said. "We're not dead yet. Hartford will rise again."

Metro on 01/28/2018