Legislators have passed several laws over the past couple of decades that limit where sex offenders can live in hopes of keeping communities safe, but some state officials say such laws often impede registrants from successful rehabilitation.

Arkansas prison officials say they must figure out a better way of housing sex offenders released from prison because a growing number of them are homeless and tracking them has become a national concern.

"They have to go somewhere," said Dina Tyler, a spokeswoman for Arkansas Community Correction. "The community reaction to sex offenders is usually what you expect, but it leads us back to what do we do with them?"

Arkansas has about 16,750 registered sex offenders, an increase from the 15,800 recorded in 2018. More than 3,236 registered sex offenders in Arkansas are incarcerated -- another problem in an already overflowing prison system.

Over the past two decades, legislation has restricted housing for sex offenders and given local jurisdictions the power to implement restrictions as they see fit.

Tyler said such residency restrictions narrow offenders' housing options. Sometimes, rules barring offenders from living within 2,000 feet of schools, churches or day care centers rule out entire cities. The rules can also extend to many transitional houses that are available for former prisoners.

It has created a problem for the state because offenders' parole plans, which offer support and increased monitoring of people formerly incarcerated, must include securing a place for the former prisoner to live. Often sex offenders who cannot find places to live serve full sentences and aren't given parole or assigned parole officers when they're released.

Without changes in the system, state officials fear a growth in sex offenders being homeless or living in rural areas with little or no support.

[Interactive map not loading above? Click here to see it » arkansasonline.com/1229offender]

TOO DIFFICULT

Research shows that restriction laws can lead to feelings of anger, hopelessness, suicide, mental illness and fear among sex-offender registrants, said Robert Lytle, a professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Sex-offender assessment information has been used to support passing housing restriction laws, but state officials say that wasn't how the information was intended to be used. Originally, it was supposed to help law enforcement agencies determine the appropriate level of community notification regarding a sex offender.

In Arkansas, anyone convicted of certain felony sex offenses -- such as rape, indecent exposure, stalking or child molestation -- must register in an open database posted on the Arkansas Crime Information Center's website. Detailed information, including the block where the offender lives and driver's license numbers, is public.

A registrant is assigned a level from one to four based on assessments conducted by the Sex Offender Community Notification Assessment Program. Level 1 offenders are considered low-risk, while Level 4 offenders are considered high-risk, violent sexual predators.

Since its creation in 1999, the Sex Offender Screening and Risk Assessment program has conducted more than 16,000 assessments, said Sheri Flynn, a state department administrator.

Lytle said sex-offender registration and notification laws were established to reduce recidivism, inform the public about offenders within their communities, and assist law enforcement in sex crime investigations.

Flynn said that with limited funding devoted to sex-offender management and a criminal justice system that is overburdened, it's crucial that Arkansas identify offenders who are most in need of the resources to protect the public.

The best way to do this, she said, is to create a "containment" approach to sex-offender management as opposed to the "banishment" method that has become popular. Flynn said the containment approach places a sex offender at the center of a system of professionals who provide assessment, supervision, transportation and treatment.

For the containment approach to work, it involves acceptance of offenders in communities that might not be willing to open their doors to such people, Flynn said.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, laws were passed across the nation that restricted sexual offenders from living in close proximity to areas where children congregate. Most of these laws use sexual assessments as a gauge.

Under Arkansas law, a Level 3 or Level 4 offender is not allowed to live within 2,000 feet of a school, certain parks, youth centers or day cares. Level 4 registrants are also prohibited from living within 2,000 feet of any place of worship.

The restrictions have created a roadblock for offenders in securing regular housing in large metropolitan areas, Flynn said.

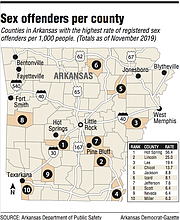

Hot Spring County has the highest number of sex offenders in Arkansas with 1,895 because the Department of Corrections has several halfway houses in the Malvern jurisdiction that are dedicated to registered sex offenders, said Paula Stitz, manager of the state's offender registry.

Halfway houses aren't usually an option for such registrants because most of them refuse to accept offenders, citing security reasons, said Robert Combs, a Level 3 sex offender and advocate.

"Even when you leave prison, the prison rules still apply at halfway houses," he said. "As you know, sex offenders aren't treated well in prison."

Combs was sentenced to five years in prison in 2004 for mailing child pornography from South Korea to North Little Rock, believing that the recipients were an 11-year-old girl and her mother. The recipients were actually North Little Rock police officers.

At the time, Combs was curator for the Army's 2nd Infantry Division Museum at Camp Red Cloud near Seoul.

He was released from prison in 2008 and made his way to Arkansas, but there was no home waiting for him.

Tyler said that without a parole plan in place, an offender is released without any state-mandated support aside from monthly check-ins.

"They might show up to the first one, but who knows if they show up again several months later," she said. "So for several months they are just off the grid. That is not ideal for anyone."

LEGISLATION

Laws on residency restrictions sprung up after some highly publicized crimes.

Washington State's 1990 Community Protection Act was the nation's first law that authorized public notification when sex offenders are released into a community. That law was passed after the 1994 rape and murder of 7-year-old Megan Kanka. Then on May 17, 1996, then-President Bill Clinton signed Megan's Law, which included such notifications.

California voters and lawmakers approved a three-strikes law in 1994 amid public outcry over the kidnapping and murder of 12-year old Polly Klaas. Richard Allen Davis, a repeat offender on parole at the time of her death, was convicted of the murder and sentenced to death.

The three-strikes law mandates life imprisonment if a felon has two or more previous convictions in federal or state courts, at least one of which is a serious, violent felony.

Marc Klaas, Polly's father, became a child advocate and established the KlaasKids Foundation in the wake of the murder. Klaas said in an email to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that he was aware of the residency hurdles that sex offenders face, but that he isn't in the business of victimizing the perpetrator.

"Their true victims face many more psychological, spiritual, emotional and physical obstacles than do the perps," Klaas said. "There are numerous studies that point out that before a sex offender is convicted, his/her victim count can be in the dozens, or more.

"The individual who kidnapped, raped and murdered my 12-year-old daughter, Polly, had a history of violent crime," Klaas said. "He always targeted women who he isolated, robbed, and beat in preparation for raping them. However, because the rapes were unsuccessful, he skirted the system and was never required to register as a sex offender. "

Mike Cooke, the sex offender manager with the North Little Rock Police Department, said that in most sex crimes the victims and offenders are acquainted beforehand.

"Are there stranger-danger type rapes? Absolutely," he said. "Those happen, but not nearly as significant as someone who is close to the family. It starts with having access to them."

Eight of every 10 rapes are committed by someone known to the victim, research shows. Of sexual abuse cases reported to law enforcement, 93% of juvenile victims knew the perpetrator, according to statistics provided by the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network, the nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization.

Still, sex-offender restriction laws continue to be passed.

Lytle noted that policymakers in some states have proposed expanding "safe zones" in their residency restriction laws to discourage sex offenders from moving into those states. He said such expansions include new focal points for restricted areas or expanding the size of restricted areas.

A 2015 Arkansas bill prevents Level 4 sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of a church or place of worship. That same year, a bill passed prohibiting Level 3 and Level 4 sex offenders from swimming areas and playgrounds in state parks.

Lytle said residents have expressed strong support for the registry and notification system, even though most don't access the database.

Combs said legislators who voted in support of sex-offender rights or who chose not to participate in votes on sex-offender restrictions find that their decisions carry consequences.

"I had a legislator approach me one time and say he knew what he did was the right thing, but he couldn't do it again because his opponent used it against him, and it almost lost him his seat," Combs said.

Katie Beck, a spokeswoman for Gov. Asa Hutchinson, said in an emailed response to the newspaper's questions that Hutchinson supports housing restrictions for convicted sex offenders.

"I do believe the public needs to be aware of the location of high level sex offenders in order to assure that children are adequately protected," Beck said in the statement attributed to Hutchinson. "In terms of housing restrictions, this is more difficult since we want these ex-offenders working and they must have a place to live. Restrictions that limit the location of offenders in terms of distance from schools or churches are appropriate."

Several studies have been done regarding the effectiveness of such buffer zones, with most concluding that proximity restrictions don't seem to have any effect, Lytle said. He also noted that Sex Offender Community Notification Assessment laws have been tied to negative outcomes -- or "collateral consequences" -- for the public, registrants and registrants' families.

All states require registrants to periodically verify their residences, employment and other information. Additionally, when registrants move or change jobs, they are expected to notify their registering agency within a specific amount of time.

"If a registrant doesn't have stable housing, then it would be difficult to keep this information current, which could turn into a registry violation that leads to re-incarceration," Lytle said.

Violating these laws also can lead to a felony charge and another incarceration.

Data shows that 3,442 felony and misdemeanor charges of failure to register and failure to comply were filed from 2013-18 in circuit courts across Arkansas. Over that same period, 612 failure to register and failure to comply charges were filed in district court.

Flynn said some offenders refuse to follow the law, but some try to do right but can't because of the restrictions.

"It becomes a vicious cycle," she said.

Most of these laws were passed based on emotion rather than research, Flynn said.

"I think we have to be able to update our information and legislation," she said. "I know the legislators were acting on the best information at the time, but information changes. "

CITY POWER

Housing restrictions on sex offenders have given cities the power to create nearly impossible living situations for registrants.

Before sex offenders can call any place home, they must check in with local law enforcement.

The sex offender manager has the authority to approve or deny any place a registrant chooses even if it's outside the 2,000-feet buffer zones, Combs said.

Cooke, the sex offender manager with the North Little Rock Police Department, said all registrants except Level 4 offenders go to see him every six months. He said Level 4 offenders report in every three months. Homeless offenders report in every month regardless of level.

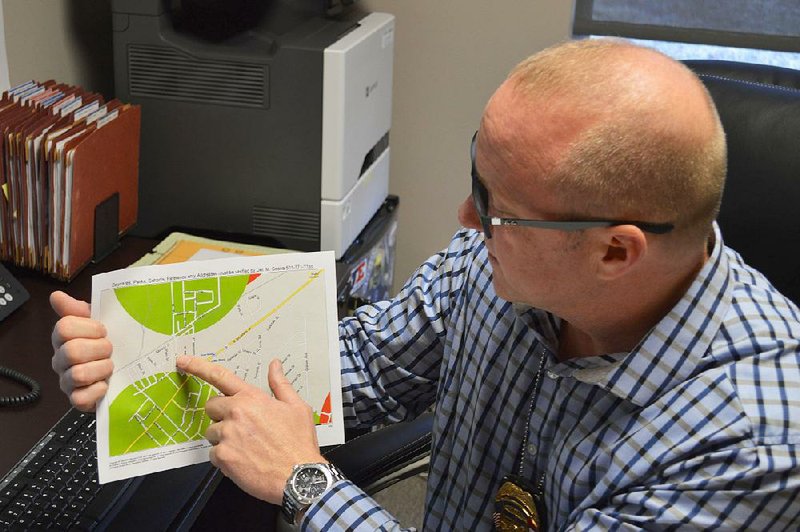

Cooke said law enforcement officials aren't required to have sex-offender restriction maps, but when he took over the program he knew it was an issue.

"At the time I asked my supervisor if I can make a map just as a guide," he said, pointing at a digital diagram of the city covered in green and red dots. "As you can see, that is not easy."

Cooke said sex offenders can live in roughly 5% of North Little Rock.

"That looks terrible until you zoom in on it," he said, scrolling to unveil multiple streets in a small gray zone on the map.

Cooke said offenders have been known to cluster in certain areas because that is what is available to them. He said he often fields calls from angry residents in those areas.

"I am still not going to tell them [offenders] they can't live there," he said. "That wouldn't be fair."

Interpretation of the 2,000-feet rule also can vary among police departments, Combs said.

"Some enforce it by 2,000 feet as the crow flies, and some do it by 2,000 feet worth of street," he said. "It changes from county to county, to city to city. It could be interpreted differently from the police department to the sheriff's office."

The notification process is also vague, and some law enforcement agencies can use it to be hostile toward sex offenders, Combs said.

"Usually the notification includes the state, name and 100th block of where you live, to avoid vigilantism," he said. "But some jurisdictions post everything."

Cooke said North Little Rock officers go door-to-door conducting community notifications. He said notifications can range into the 300s when it comes to a Level 4 registrant.

Most residents who receive notification ask the same question: Is this guy going to do it again?

"I believe all of them are capable of doing it again," Cooke said. "Do I think he is going to? Probably not, but I can't tell them [community members] that."

City officials in some states have capitalized on the 2,000-feet-from-parks restriction and created "pocket parks" strategically around their towns, said Carla Swanson, executive director of a sex-offender rights advocacy group called Arkansas Time After Time. She gave examples of such places in Arkansas, but government officials wouldn't confirm the parks' existences.

The idea of pocket parks has been around for several years and gained attention when Los Angeles built three in 2005.

"Unfortunately we have heard about this pocket parks idea before," said Janice M. Bellucci, attorney and executive director of California Reform Sex Offender Laws, a nonprofit organization that advocates for the rights of people convicted of sex crimes. "It went from the Pacific Ocean and just moved east."

Jefferson County Sheriff Lafayette Woods Jr. said in an email that, from a law enforcement perspective, he favors concepts such as pocket parks.

"With rehabilitation comes housing, and we understand that no one -- including members of law enforcement -- want to see sex offenders living among children," Woods said. "The creation of tiny parks force convicted sex offenders to find alternate residency; ultimately eliminating the potential for them to re-offend or remain a threat to children or would-be victims."

He also noted there is a downside to such thinking.

"However, as a result of sex offenders losing stable housing, they become increasing harder to track but also more likely to commit another crime," Woods said. "It seems to be a double-edged sword when you weigh the pros and cons."

Nationwide research has shown that Sex Offender Community Notification Assessment laws also lead to increased public fear, Lytle said. He said communities get directly involved sometimes, exerting political capital, intimidating the registrant or blocking the registrant's access to jobs.

Flynn said it's important for people to remember that the ideal is to create a situation in which the sex offenders will not to re-offend.

"By creating circumstances where they can't live or work or check in with support, then we aren't doing anyone any favors," she said.

HOMELESSNESS

A major concern among government officials is an increase in the population of homeless sex offenders.

"A homeless sex offender is the worst-case scenario," Stitz said. "The offender is mad, doesn't have a home and is blaming the world. That is not a good mental state."

Lytle said research shows that restrictions on places to live increase homelessness among sex-offender registrants. Also, stable housing is a precondition for successful reintegration for felons, but it is difficult for them to secure.

In states like California and Florida, the homelessness sex-offender problem escalated until it caught national officials' attention, Bellucci said.

Significantly higher proportions of transient sex offenders were found in counties with larger numbers of local-level restrictions, wide-distance buffer zones, higher population densities and expensive housing. Homeless offenders were more likely than non-transients to have registry violations, according to a 2015 study published in the Social Work and Criminal Justice Publications.

Despite monthly check-ins, law enforcement officers never know where a homeless registrant actually lives, Cooke said.

"They can say 'I am living in some woods,' but how do you check that? When do you check that? Are they even telling the truth?" he said.

Swanson said Arkansas stands to face such a homeless sex offender problem soon if restrictions aren't adjusted.

"Unless Arkansas wants to pick a city for all sex offenders to live in, then we are going to have to change some things," Swanson said.

The situation is complicated, Tyler said.

"It's a conundrum," she said. "What do we do with them? There is just no easy answer."

SundayMonday on 12/29/2019