A while back a reader sent an email about using a continuous glucose monitor. They are new to many people so I figured it might be worth looking into.

On the website of Everyday Health (everydayhealth.com), I read about a new device approved by the FDA in June. An FDA news release discusses the device, the Eversense Continuous Glucose Monitoring System. There are several other brands on the market now.

I guess if we are going to use something that can mean life or death, FDA approval might be in the plus column.

If you are not familiar with these devices, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (niddk.nih.gov) says that the devices automatically track blood glucose levels throughout the day and night. You can see your glucose levels any time at a glance, and can review the changes over a few hours or days, and see trends.

Such monitoring could help diabetics make better decisions about food, physical activity and medications.

I called the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and was put in touch with Dr. Peter Goulden, the UAMS diabetes program director. He says that the continuous monitor is "arguably one of the biggest steps toward diabetes care in the last few years. It frees the patient from the challenge of regular frequent finger-stick glucose testing."

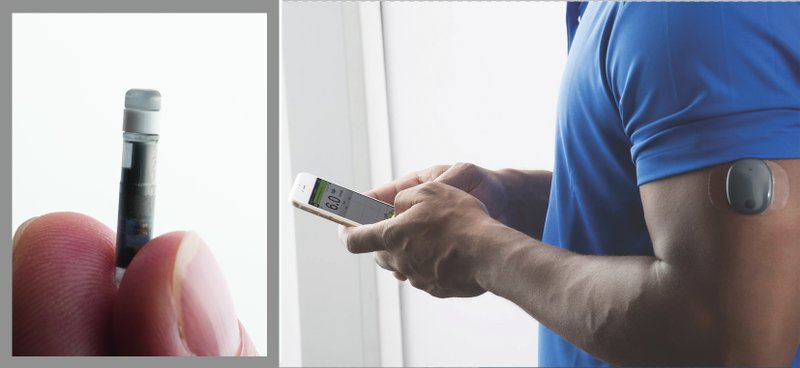

The gadget consists of three parts — a wireless monitor, a transmitter and a sensor that is inserted under the skin of the arm or belly. It's about half an inch long. There are several layers to the sensor that are able to provide measurements every few minutes of the glucose in the fluid surrounding the sensor. The measurements are converted into electrical signals and transmitted to a receiving device or monitor.

The monitor can be part of an insulin pump or a separate device small enough for a pocket or purse. Some monitors send information directly to a smartphone or tablet. And some have features that include:

■ An alarm that sounds when levels get too high or too low.

■ The ability to note meals, physical activity and medicines on the device.

■ The ability to download data to a computer or smart device more easily to see glucose trends.

Some models will send the information right away, maybe to a parent, partner or caregiver. For example, if a child's glucose level drops dangerously low overnight, the monitor could be set to wake the parent in the next room.

Researchers are working to make monitors more accurate and easier to use, but several sources said that a finger-stick glucose test twice a day to check the accuracy of the device would be needed.

Goulden says that the monitors work well for Types 1 and 2 diabetics.

In the last couple of years, the insulin pump devices that integrate with continuous monitoring devices have been made so they can vary the dose of insulin given minute by minute, according to the measured glucose level. This is essentially what the pancreas does.

The institute states that continuous glucose monitoring is one part of "artificial pancreas" systems that are now in use.

In 2016, the FDA approved a type of artificial pancreas system called a "hybrid closed-loop system." It tests blood-sugar levels every five minutes day and night — using continuous glucose monitoring technology — and provides the right amount of basal insulin, which is a long-acting insulin, injected through a separate pump.

Along with the version that allows us to read it ourselves, there is a diagnostic version. This is implanted in the body at a doctor's office. The patient goes back after several days to have the monitor removed and the information reviewed by the doctor.

As with many machines, the monitor will need to be calibrated from time to time for accuracy.

According to Goulden, a prescription is needed for the device, which will generally include a receiver and transmitter. In addition, a sensor will be prescribed. It will be replaced every 10 to 14 days, depending on the type of device.

He says it is important to understand what insurance will cover, because many policies won't cover the expense unless the patient requires four injections of insulin a day.

So for those who don't need insulin injections or don't need that much, and who have high deductibles and a lot of out-of-pocket expenses, a continuous glucose monitor would not be a viable choice, Goulden says.

Email me at:

rboggs@arkansasonline.com

Style on 01/14/2019