An unusual band of cold weather descended on Columbia, Mo., the week the True/False film festival was to take place, culminating in a subzero day on Sunday, the closing day. This was my fifth year attending this most amenable of festivals, and I'd never seen it as cold and wintry as it was this week.

The cold had a predictable dampening effect on the proceedings: One tweet sent on Saturday morning reflected the relative emptiness of a screening, a virtually unprecedented occurrence at a festival whose every show is generally packed tight. In direct contrast to last year, which offered enough sunshine to at least mimic a spring day, with some students striding around in shorts and T-shirts, this was dead cold, with a forceful wind that had a tendency to curl up around your ankles and whip up through the bottom of your coat. I ran into one critic who had driven up for the festival from near Little Rock, who had to leave early on Saturday to avoid the oncoming onslaught of snow that he feared would make his mountainous return impassible.

Weather patterns and their subsequent ramifications of our impending environmental collapse aside, what struck me about this year's edition of this documentary festival was the diversity of the offerings. Not just in a racial and gender sense, though, as always, there was a wealth of representation, but also in tone and approach. I spent one entire day watching films of such depressing potency I left the theaters contemplating the hopelessness of it all; and another happily surfing through vastly more light and encouraging fare, able to see the ineffable humor in the human condition and the amusing absurdity of our very existence on a spinning rock in the middle of the cosmos. Vive la difference! Now, let's play the superlative game.

Most Depressing: Dark Suns. As you can imagine, this is a pretty crowded field (docs, on the whole, aren't known for their white clouds and fluffy kittens) but for sheer, oppressive, slump-your-shoulders-and-sob disheartening, look no farther than Julien Elie's devastating film, which begins as a sort of investigation into the continued problem of missing women in Mexico, and ends up traversing around the country in six chapters, disseminating the toxic levels of corruption, villainy, and lawlessness that currently preside in the country. So compelling and encompassing is Elie's argument, by the end it's impossible to see any way out of the horrific, crime-infested wormhole the country and its citizens have been sucked into. By the end, watching a group of mothers sift through desolate locations in the mountains looking for the remains of their missing loved ones, a situation where the best they can hope for is to find a piece of a skull or a tibia bone that can be DNA linked to their child so as to at least find a dram of closure, it hits you just how untenable this situation has become. I love Mexico, and have always found it an exceedingly warm and hospitable place to visit, but this film does the visitors bureau no favors with its unflinching honesty.

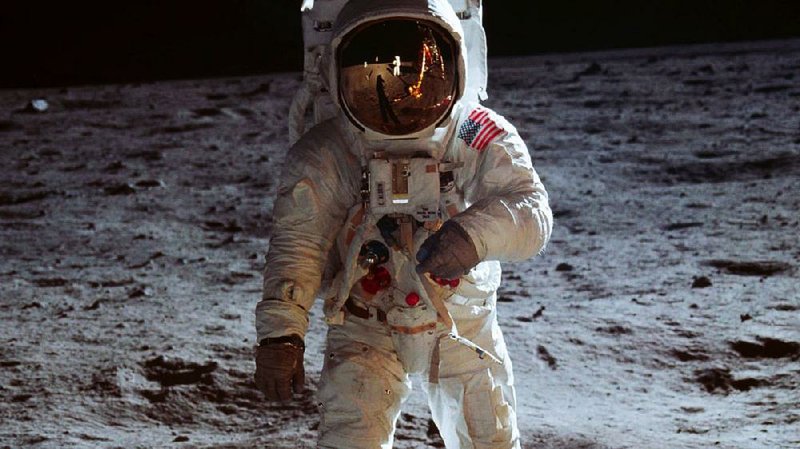

Most uplifting: Apollo 11. You might well have seen other films about the first successful manned flight to the moon -- even last year, with Damien Chazelle's underrated First Man -- and feel the story has been worn through at this point, but you would be mistaken. Todd Douglas Miller's film, a composite of previously unreleased NASA footage, tells us the familiar story, the lead up to the mission, the build-up to the launch, the eight-day-long ordeal of the three astronauts in space, and their return, but seen from otherwise unseen angles and a different perspective (with a soundtrack of the radio transmissions between mission control teams and the astronauts themselves), we get to see this stunning event much more as the rest of the world did back in 1969. There are no new revelations involved here, nothing that will reframe the event in our cultural history, but to see it through the eyes of the expectantly watchful crowd, stuffed onto parking lots and bay banks across from Cape Canaveral, is to witness this epoch in history all over again. It's difficult to explain how effective it is in re-capturing that sense of wonder and hope that swept over the country that week in an otherwise tumultuous year, but it most certainly does.

Most unsettling: Cold Case Hammarskjold. Mads Brugger's film begins innocently enough as a murder mystery -- in 1961, a plane carrying Dag Hammarskjold, then the United Nations Secretary General, and his staff, crashed while en route to a peacekeeping meeting in the Congo, a crash that has long been rumored to have been an assassination -- but what begins as an interrogation into a long ago death, ends up in a much different, and wildly disconcerting, place. Brugger, known for his own brand of gonzo journalism, puts himself front and center in the film, and his lamentations when he seems to run aground about halfway through, run the gamut between funny and outright aggrievement (for reasons he is happy to explain, he casts himself as the director, who always wears all-white, like some kind of Bond villain), but when he and his investigator's exertions eventually lead to a meeting with a former operative of a top-secret mercenary organization, which may or may not have carried out the assassination, along with much worse operations, the tone of Brugger's film takes on a much more harrowing edge. In the end, the film's (as yet unsupported) claims suggest a much deeper tangle of malfeasance, and the stuff of a conspiracy theorist's worst nightmare come to pass.

Most Illuminating: American Factory. Steven Bognar and Julie Reichert's film is about the reopening of an old, shuttered GM plant in Dayton, Ohio, by Fuyao, a major Chinese company that manufactures car windshields. What begins with hope for the newly hired American workers, many of whom were jobless since the GM plant closed years before, and a possible way forward in the global economy for two countries as culturally different as China and the United States, becomes instead a relief map of exactly the ways the dream of a multicultural workforce gets torn apart by the political reality of the two nations. To the Chinese management, and the many workers brought over from their home country to help facilitate the new merger, the Americans are "lazy" and unwilling to work at a productive enough pace to their liking. More complicating, the disgruntled American employees, tired of the low wages and inhospitable working conditions, start to grumble about joining a union. It's not until a group of Americans goes over to China in order to better learn the Chinese methods, that it becomes clear where the trouble lies. In China, the workers get one or two days off a month, and many get to see their families, including young children, only a couple of times a year. To the Chinese businessman, to be properly "productive" is to devote all of your life energy to the company to better increase their profits; anything else is considered subpar and inefficient. To the growing consternation of Cao Dewang (a squat, round-faced man with a deliberate smile and an autocratic demeanor), the billionaire chairman of the company, the U.S. workers take hold of the union possibility, right up until Dewang decides his company needs to take action to quash the effort.

Best Moment: Miss Clara Ward's collapse, Amazing Grace. By the second night of her unforgettable 1972 recording session at a Baptist church in the still-reeling L.A. neighborhood of Watts, Aretha Franklin had already taken the small-but exultant crowd to sublime highs numerous times (amazingly, for the first night, the church was remarkably less than entirely full, by the second night word had certainly gotten out, and the place was packed by churchgoers and music fans, including Mick Jagger), but toward the end of her last night, she reaches a new level, and the crowd becomes increasingly besotted, dancing in the aisles, and raising their hands in rapturous testifying. In front of her father, the Rev. C.L. Franklin, and gospel singer Clara Ward, Franklin's rendition of "Precious Memories" sends the crowd all the way over the edge. As Franklin pours her soul out into the hot and humid air, near chaos reigns in the church, and Ward, up until that point quite stoic, leaps up from her seat and dances with wild abandon before falling deliriously back into her chair at last, a final gesture in testament to the blazing power with which Franklin has charged the place.

MovieStyle on 03/08/2019