Rene Henderson of Conway remembers when she was just 9 years old, having to wake up early and hop in the back of a truck in the dark to go chop cotton in the Delta.

“It was hot, but what I really remember, I could look up the rows and see kids — the white kids, the boss’s kids … playing up by their big white house. I thought, ‘Why am I out here doing this rather than up there playing with the kids?’ I didn’t really get that; I was just told I can’t.”

She knew right then that she wanted an education.

“I loved learning because I just knew I had to get myself out of those cotton fields,” she said.

The oldest of four children and the only girl, Henderson was raised in Earle by a single mother with a third-grade education. Henderson excelled in school and graduated as salutatorian of her high school class — bumped out of the No. 1 spot by a transfer student with whom she is friends to this day, she said.

Henderson, 56, said she decided to become a nurse because she saw how frustrated her mother was trying to take care of Henderson’s grandmother, who came to live with them after she had a stroke

“I said, ‘There has to be a better way. I’m going to go learn a better way to help,’” Henderson said.

She was awarded a scholarship to attend the University of Central Arkansas in Conway, where she earned a nursing degree and a master’s in nursing with an education certificate.

Her career has included working at the Conway Human Development Center with adults with disabilities, which she said confirmed her love of nursing; serving senior citizens as a director of nursing homes for two decades; then serving college students as a teacher of nursing at three institutions of higher education: UCA while she was getting her master’s; Petit Jean Vo-Tech, now the University of Arkansas Community College at Morrilton, Baptist Medical Center; and the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff for several years.

And along the way, she became a community activist.

Henderson was honored for her work with the Humanitarian Award, presented by the Faulkner County Unit of Church Women United. She received the award Oct. 4,

which also happened to be National Diversity Day.

“I was just overwhelmed by it,” she said of the honor. “I never even categorized my work under human rights.”

Julie Adkisson of Conway, a member and past president of the group, said that when she thinks of Henderson, the word that comes to mind is “indefatigable.”

“She just seems tireless,” Adkisson said. “She’s curious, and she likes to get to the bottom of things. She likes to lift up things for everyone’s awareness that we probably wouldn’t know about otherwise, and she’s really just relentless to help other people.

“She is always a bright spot in a civic or political meeting, calling our attention to an opportunity to serve or an injustice to be righted or a need to be met,” Adkisson said.

Henderson lists 15 organizations as those she actively participates in, including Moms Demand Action, the Faulkner County Coalition for Social Justice and the Faulkner County Democratic Women. She is also a member of Greater Friendship Church and serves as statewide health director for the Regular Arkansas Baptist Convention, making sure all the member churches have a health program.

When one of her daughters had a near-death experience at school when the school’s nurse was at another school, “I testified in the Arkansas Legislature and wrote an article about the need for more school nurses, which ended up being catalogued in the Library of Congress,” Henderson said.

One of her earliest efforts, she said, was to advocate for Conway’s poor elementary students to be able to attend field trips to places such as Sea World.

Henderson is a familiar face at public meetings, including the Mayflower School Board and Faulkner County Quorum Court meetings.

When she heard at a Mayflower School Board meeting that district test scores, particularly in English, were lagging, Henderson decided to do something about it.

“I said, ‘What can we do to get the community involved?’” Henderson said.

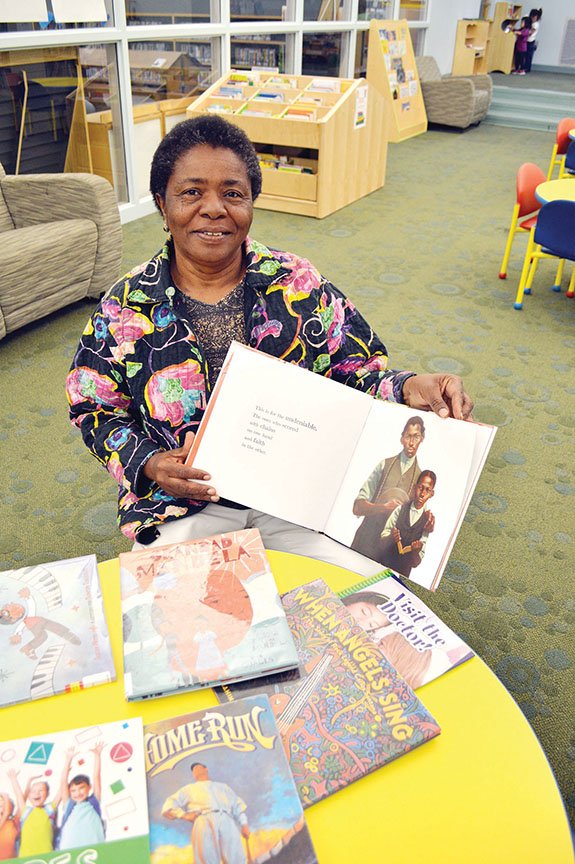

Earlier this month, she launched the Mayflower Reading Buddy program in conjunction with the school district.

She said she has gotten stacks of donated books, and she has started distributing them in neighborhoods, explaining to families that they don’t have to return the books.

She said socioeconomics come into play. She was talking to a group of Mayflower students, and a third-grader said, “I don’t go to the library.” When Henderson asked why, he said, “If I lose a book, my momma has to pay $20.”

“That tore me up,” she said. “In some families, $20 might as well be $200.”

She said she gave the boy a couple of books and told him he could keep them.

Volunteers are asked to read to students at the elementary school. Henderson said Lt. Gov. Tim Griffin, a Republican, contacted her to participate, and she has many men and women signed up from the Faulkner County Democratic Party.

“It’s not a partisan issue,” Henderson said of promoting literacy. “I’m just glad to see people interested in our kids’ future.”

Children who can’t read are often headed toward a life of crime, she said.

Henderson said her goal is to get more people involved in donating money, time reading and books for the children.

She also ran unsuccessfully last year for a position on the Faulkner County Quorum Court.

“When I was on the campaign trail, people talked to me about some raw areas of their lives,” she said. “They talked about flooding in their yards and not knowing their resources or that there were county offices that could help.”

Henderson connected those people with resources and tried to raise their awareness.

Her platform included equal representation for small businesses and the underprivileged, safe and fair elections, disaster recovery and preparedness, and restoration of voting rights to the formerly incarcerated.

One of her dreams is to see the establishment of empowerment centers, where nonviolent, minor offenders can go during the day instead of going to prison and get services such as mental-health intervention and life coaching.

“I’m disappointed and discouraged that the face of our government is what it is,” she said, referring to the lack of diversity. The Faulkner County Quorum Court is all white and has only one woman.

Henderson said she remembers as a child going door to door with her mother, who handed out cards for candidates. She didn’t know it was called canvassing, “but what I did realize is that she was doing something to help make the lives of others better in her own able way.”

“Mom was poor with a capital P,” Henderson said. “It is poor to where you have to save, save, save. You can’t afford to throw out anything — food, or leave it on your plate.

“I didn’t even know what it was like to go to Burger King or McDonald’s,” she said. Henderson said she’d never eaten a slice of pizza until she came to the University of Central Arkansas in Conway when she was in high school and participated in the Model United Nations.

Her family lived 3 miles from school, and they didn’t have transportation. Henderson couldn’t participate in basketball or school plays because of the practices and rehearsals.

“My mother cried. She said, ‘We just can’t afford it.’”

Henderson said her hardworking mother was a cook at a truck stop, and Henderson, when she was 14, got a job as a dishwasher at the same truck stop and left the cotton fields in the dust.

Henderson and her mother had the same boss at the truck stop. The married man, a grandfather, offered to pick up Henderson from school and take her to work every day.

“One day, he took a different route,” Henderson said quietly, as she sat in a coffee shop in downtown Conway.

The man explained to Henderson that he gave her a ride to work for free, but he wanted something in return.

“He said, ‘You know I don’t charge your momma a dime.’ He said, ‘I thought we could just visit,’” she said.

Henderson said he told her, “I’m not going to hurt you,” but he wanted to inappropriately put his hands on her body.

“It was a hard place to be in, feeling like your momma needed the money. I was afraid to speak up. I didn’t want my mother to lose her job,” Henderson said.

For a year, the man picked her up from school, stopping along the way to abuse her before taking her to work, she said.

“I just kept thinking there’s a way out through education. I thought education was the way out of all these horrible things. I just thought, ‘Keep studying; keep making good grades.’”

The abuse ended when she got a boyfriend, Henderson said, and she told him what the man was doing to her.

“He said, ‘We need to tell somebody,’ but I didn’t want my mother to lose her job,” Henderson said.

She told her boss that she had confided in her boyfriend about the abuse. The man didn’t touch her again, but the rides ended.

“I stopped working then,” she said.

When Henderson got to UCA, it was a drastic change from her life in the economically deprived Delta.

“I saw girls wearing pants with Tommy Hilfiger, and I was like, ‘Who is Tommy Hilfiger? Oscar De LaRenta?’ It was like I had gone overseas,” she said.

While she attended UCA, she worked the 4 p.m. to midnight shift at what was then AmTran, the bus factory in Conway. That’s when she experienced sexual harassment.

“I didn’t know it had a name,” she said.

Henderson said she rebuffed the sexual advances of two supervisors, and she went from an easy line job, working with small parts, to lugging big tubs and being told, ‘Go wire this bus,’” which she had never done.

She quit her job at AmTran and was hired at the Conway Human Development Center.

“This was just confirmation that this is what I wanted to do,” she said of nursing. Henderson said she loved the “total care” she was able to give residents.

After she got her bachelor’s degree from UCA, Henderson said, she did a teaching stint at UCA while working on her master’s degree there.

She then went to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences to work as a nurse in the high-risk Women’s Health Unit in obstetrics, which also served as an overflow unit for other patients.

Henderson remembers that the family of one patient didn’t like black people and asked for a white nurse instead of her. The supervisor explained to the family that Henderson was the only one certified in chemotherapy. Henderson said the family was asked whether they wanted a white, uncertified nurse, or a black, certified nurse? They chose

Henderson.

When she cared for the woman, Henderson tried to leave before the family arrived to visit because Henderson said she knew she made them “uncomfortable.”

One day, “the woman grabbed my hand and said, ‘Don’t leave,’” Henderson said.

And when the woman was dying, Henderson said she was going to leave her alone with the family to say their goodbyes.

“She said, ‘I’d really like you to be the person with me when I exit.’” Henderson hoped that made a difference in the way the family viewed black people.

Henderson went to Conway as director of nursing at a nursing home, and she loved working with the elderly because she said she got to “hear their life stories.”

Henderson worked as a director at nursing homes from age 21 to 40, and became a consultant to nursing homes, too.

She said her three daughters were “raised up in nursing homes,” and they would take their toys or homework to her office. “They absolutely had a lot of grandmas in the nursing home,” Henderson said. Her daughter Marcia Moore is director of nursing at a Conway facility.

Henderson and her first husband divorced, and she remarried. Her husband, Jimmy, a 22-year veteran of the Army, died five years ago.

“He supported my work,” she said.

She retired in 2008, but then the director of a nursing home in McGehee asked her to help.

“It was about to be closed by the state,” Henderson said, and she was asked to come and “get it going.”

She kept her house in the Gold Lake community near Conway and Mayflower but stayed in McGehee during the week to work.

Henderson was able to pull the nursing home out of dire straits.

“We came up with no deficits in nursing,” she said.

Being retired just means she has time for nonstop advocacy work, wherever she sees a need.

“Time is out for being complacent and not being involved, and there are so many ways to get involved,” she said.

In her acceptance speech for the Humanitarian Award, she said the honor “has confirmed for me that every mustard-seed action on behalf of others matters in real time as people attempt to lead their lives.”

Henderson is a long way from that little girl who rose in the dark to chop cotton and suffered abuses and inequality silently.

But not so far that she’s forgotten. And that’s why she fights for what’s right.

Senior writer Tammy Keith can be reached at (501) 327-5671 or tkeith@arkansasonline.com.