The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette is serializing the new book from Blant Hurt, who has been been thrilled, tantalized and tormented by his favorite college football team, the Arkansas Razorbacks, over the past 50 years. Selections from his book will be published weekly through Nov. 15.

PROLOGUE

On the occasion of my 59th birthday, which fell in the middle of the college football season, my mother gave me a plaque that read, “Thankful, Blessed, & Football-Obsessed.” At first, I didn’t think much about her little gift. This plaque, the size of a thigh pad, was like those throwaway wall hangers that say, “What Happens at the Cabin Stays at the Cabin.” Yet the words in bold type stuck with me and I wondered how it had come to pass that my mother—at this advanced stage of my life, much less hers—viewed one of her son’s defining qualities as being “Football-Obsessed.” Wasn’t such a take on me rather narrow? After all, like all of us I considered myself a man of varied talents and interests. Even so, I couldn’t deny that the words on this plaque, which bore a $4.00 price tag from TJ Maxx, my mother’s favorite store, were indeed accurate.

Since I was 9 years old, I have been thrilled, tantalized and tormented by my favorite college football team, the Arkansas Razorbacks. What an exhausting half-century it has been. My fandom—you could even call it a fanaticism—took root in my youth with one game that captured my imagination, in no small part because my father was a fan too and, given his example, my passion was as inevitable as the removal of the training wheels from my bicycle.

The idea of writing this book came to me in the wake of the 2016 Belk Bowl, which, like so many football games and practically any football season, and even with life itself, had not gone as I had expected. The Arkansas Razorbacks blew a 24-0 halftime lead against Virginia Tech. This collapse, which I likened to a 100-Year Flood even though it came just one game after a similar second-half collapse, left an ugly watermark on my psyche. But it also agitated my curiosity: Why did the outcome affect me so much? Why, as a man well into my 50s, couldn’t I just shrug off this loss? Why did it color my entire holiday season?

In the spirit of self-discovery, I made a few notes. At first, the act of writing about the tenacious grip that Arkansas football has had on me for nearly half a century seemed wasteful. Didn’t Razorback football already occupy enough space in my head? Only months before this Belk Bowl meltdown, I’d penned a column for the local newspaper in which I had half-jokingly suggested that during football season my IQ drops at least 20 points.

On the other hand, what else had ever affected me so viscerally? What, save the very thump-thump of my heart itself, was such an integral part of my past, present, and future? The more I thought about it, the more I came to see that my fandom was a unifying theme of my life, if not the unifying theme. It has colored and infused my entire being, and it’s never been something I could compartmentalize. There’s always been an interplay between it and every epoch of my life, and it has affected every significant relationship I’ve had, including those with my father and mother, my sister, my grandparents, my uncles, my childhood friends, my frat brothers near and far, my current wife and stepchildren, my ex-wives, my business colleagues, my beloved teachers. No one I’ve ever been close to has escaped the turbulence of my fandom.

So I pressed on. And as I wrote I sensed that my story, while rooted in specifics unique to me and my state and my times, also touched on aspects of the universal. It’s never been lost on me that if I’d been born 70 miles to the east, just across the Mississippi River, I would surely have lived my life as a Tennessee Volunteer fan. Ditto if I had grown up in Youngstown, Ohio, and was nutty about the Ohio State Buckeyes. So I invite all who are similarly afflicted to read on—like it or not, I suspect you’ll find a bit of yourself in my story.

CHAPTER ONE: THE BIG SHOOTOUT

I was born on October 19, 1960 or, as it was known in our household, three days before the Arkansas-Ole Miss football game. My father, a 21-year-old die-hard Razorback fan, faced a dilemma: Would he tend to his wife and newborn son in Jonesboro, or abandon us for the game down in Little Rock, some 120 miles south? When he wasn’t harvesting cotton with his new one-row John Deere cotton picker, my dad served as an aide-de-camp to a gubernatorial candidate who lived down the street. Dad’s side job was to drive this candidate wherever he desired to go, and on this particular Saturday both of them desired to be at Little Rock’s War Memorial Stadium.

I’ve never had a problem with Dad’s choice, especially considering that Ole Miss was ranked number two in the nation, while Arkansas, under head coach Frank Broyles, was ranked 14th and had just beaten Texas 24-23. It was indeed a pivotal matchup. Besides, if Dad had stayed home, what exactly could he have contributed to my care? All I was doing was eating and sleeping, peeing and pooping. My mother, stricken with postpartum depression and coming from a family of non-football fans, didn’t see it that way. She was further put out that Dad had changed my name on my birth certificate to his name, his father’s name, his grandfather’s name: I, therefore, became William Blant Hurt, IV, cementing my line going back to a 20-year-old man from Bristol, England, who’d boarded a ship to Virginia in 1701.

In hindsight, I have to believe that both my dad and the erstwhile gubernatorial candidate, who eventually decided not to challenge Orval Faubus in the Democratic primary of 1962, were on to a good thing. Little Rock had suffered through the desegregation crisis in 1957, and the national perception of Arkansas was quite unfavorable. In 1958, Frank Broyles was hired and lost his first six games. But in 1959, the Hogs had gone 9-2, their most wins ever in a season.

Though the Razorbacks lost this first-of-my-life matchup against Ole Miss on a controversial call (my father, to this day, swears the game-winning field goal was wide), the Hogs went 8-3 in the year of my birth; then 8-3 in 1961; 9-2 in 1962; 5-5 in 1963; 11-0 in 1964, including the national championship; and 10-1 in 1965. The cover of the November 8, 1965, “Sports Illustrated” carried the headline “Arkansas—The New Dynasty.”

My life throughout the 1960s was almost idyllic. I went to a good public school where all the boys played Red Rover on the blacktopped playground. My mother made sure my sister and I were regularly attendees of the First Methodist Church. My enterprising father found lucrative outlets for his prodigious energies and imagination. Our new one-level brick house was surrounded by open fields, where the kids in our neighborhood came together to play sandlot baseball. When it rained, we frolicked in the ditch banks and spent days at our hideaway in the nearby woods that we called Rattlesnake Camp. Our idea of being mischievous was to throw crab apples at one another. As the fireflies and mosquitos came out in the evenings, my mom and dad watched Walter Cronkite on CBS News. My paternal grandparents lived just up the hill, and my maternal grandparents lived only two miles away, out near the gladiola farm. I knew it was my bedtime when I heard Johnny Carson’s opening monologue on “The Tonight Show.”

I really latched on to Razorback football only near the end of the 1969 season, after the Hogs had echoed the dynastic years of 1964 and 1965 by reeling off nine in a row. It’s odd, but before the 10th game of that season I have few memories of Razorback football. A kid learns when he’s ready to learn. From this game on, I can remember more than I sometimes wish to.

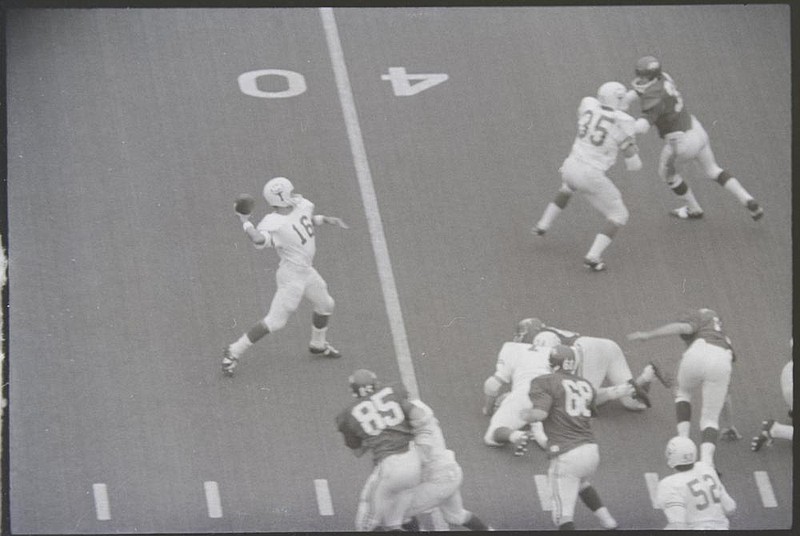

The date was December 6, 1969, a Saturday. I was rapt as the announcer on television gravely delivered the lead-in: “Razorback Stadium, Fayetteville, Arkansas, where the unbeaten and top-ranked Longhorns of Texas, with the nation’s most awesome rushing attack, meet the unbeaten and second-ranked Razorbacks of Arkansas, led by quarterback Bill Montgomery, in a game that should decide the national championship.”

With my mom and dad at a game-watching party, I was at my grandmother’s house, which smelled of roast sirloin, her specialty. I darted in from her living room to nab a thick-cut end piece full of peppery flavor, then hustled back to one of the throne-like easy chairs. This living room of my grandmother’s was a citadel of comfort with her state-of-the-art Zenith TV (complete with a remote control, rare in those days), huge ottomans for the feet, plastic drinking glasses that didn’t sweat when filled with ice water, table-top buttons to turn the lamps on and off with minimal strain and, within arms’ reach, her mail-order catalogs, including “Hammacher Schlemmer” and “Horchow,” dozens of magazines like “Sports Illustrated” and “National Geographic” and “Southern Living,” and stacks of the “National Enquirer” and “The Star,” which she referred to as her Funny Papers.

Dark-haired and hazel-eyed, my grandmother was dressed in a drapey, red-tinged muumuu and black slippers adorned with red rhinestones. Yet despite all of her creature comforts, she was hardly a softy. Years before, my grandfather had taken her to a gathering of John Deere dealers, where she’d refused to shake the hand of one of the executives in the receiving line because he wore an “I Like Ike” button. On this particular game-day Saturday, I’m confident she hated the Texas Longhorns at least as much as she did any random button-wearing Republican.

The images flicked by on my grandmother’s television. There was the pregame prayer by the Reverend Billy Graham, the panning shots of the Razorback cheerleaders, the overflow crowd set against the leaden December sky. In a quaint humanizing touch, 11 players from each team were introduced, one by one, in front of the camera, each posing without his helmet when his name was called. A helicopter landed near Razorback Stadium and soon images of President Nixon appeared. My gosh, I thought, if the Arkansas Razorbacks are important enough for the President of the United States to helicopter into the Ozark Mountains to watch them play, then aren’t I justified in giving my heart and soul to this team? Before the 1969 season, the legendary Roone Arledge of ABC Sports had made a bet that Arkansas and Texas would be the two best teams in college football, so he had asked them to move their game, typically played in mid-October, to the end of the season. Both Arkansas and Texas had won their first nine, setting up what was billed nationally as The Big Shootout.

The Big Shootout. Boy, did this speak to me. It was two heavily armed gunslingers at the OK Corral, good guys versus bad guys, light against dark. The quarters clicked by: At the end of the first, it was 7-0 Arkansas. At halftime, it was still 7-0. By the end of the third, the Hogs led 14-0. As all this unfolded, my grandmother’s living room was filled with her shouts, cheers, her oohs and aahs. Her favorite expletive was a rapier-sharp “dammit,” and beside her, at the ready, were the white dinner gloves she sometimes donned to keep from biting her fingernails.

Then came the final score: 15-14 Texas.

Looking back, many of the finer points and mind-bending absurdities of this so-called Game of the Century were lost on me. How did my team lose a game in which the other team turns the ball over six times? Why, with 10:34 left in the fourth quarter, did Coach Broyles decide to throw a pass, subsequently intercepted, when Arkansas had the ball inside the Texas 10-yard line? Why didn’t he just play it safe and kick what would’ve been the game-clinching field goal? How did James Street, facing a fourth-and-three with 4:47 left and his team down 14-8, fit that pass over two cozy defenders and into the outstretched arms of tight end Randy Peschel?

I had no idea where my 5-year-old sister was. I was just glad she wasn’t in the living room to annoy me by standing in front of the television, as she sometimes did when I watched “Little Rascals” at our house after school. She was probably taking a long nap, as was my grandfather. Nothing got between him and his afternoon nap. Regardless, from my vantage point, truly bad forces had been loosed upon the world—namely, that tawny-haired clarinetist in the Texas Band. As the dramatic fourth quarter unfolded, a close-up of her face kept appearing on the TV screen as she cried and cheered and ultimately flashed the Hook ’Em Horns sign in victory. It was as if this tearfully jubilant gal was shooting me the middle finger even before I understood what it meant.

I teared up when President Nixon, brandishing a wooden plaque of some sort, went to the Texas locker room to declare the Longhorns national champions. “For a team to be down fourteen to nothing and not to lose its cool,” he said, “proves that you’re number one, and that’s what you are.” At that moment, I can’t say that I actually disliked Nixon, but years later it hardly surprised me to learn that he was sometimes called Tricky Dick. All I knew was that my team had lost The Big Game, and the purported Leader of the Free World was in the wrong locker room.

My grandmother fixed me a roast beef sandwich and, with her red rhinestone slippers in hand, retired to her bedroom. I poured myself a glass of milk, alone with nothing on the TV except “The Lawrence Welk Show” and “Hee Haw.” I picked up a copy of “National Geographic,” which I typically found boring, and I even read the garish headlines in the “National Enquirer.” Anything to divert me. Such torment, the gloom after losing a momentous game, the haunting what-ifs, the realization that the outcome can never ever be changed and there will be no second chance. I missed my mom and dad.

The following Tuesday, after school, I went back to my grandmother’s house to see the latest “Sports Illustrated.” There, atop the knee-high pile of magazines on the floor beside her easy chair, was the new issue featuring a cover photo of quarterback James Street on his pivotal 42-yard touchdown run early in the fourth quarter. My eyes went to the headline: “Texas Gambles Its Way Past Arkansas.” Back then, any story on the cover of “Sports Illustrated” was a big deal. I picked up the magazine but couldn’t bear to open it, so I just placed it back on top of the pile. For good measure, I covered the “SI” with one of my grandmother’s “National Enquirers.”

Even in my crushing disappointment, I had been captivated by the high-stakes drama of The Big Shootout, the frenzied spirit of the home-state crowd, the full-throated build of the Woo Pig Sooie call, the cheerleaders in crimson sweaters, the players in their red helmets bearing the logo of the charging Razorback. I relished the sense that my team was at the center of what I took to be the entire universe, and I was somewhat justified in this: The Big Shootout was viewed by one in four Americans, and drew a Nielsen rating of 52.1, swamping “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In,” the era’s highest rated TV show at 31.8.

And so, with this game, the 1960s came to an end. Over the decade, even with this stinging loss, Arkansas had won more games than any college football team except Alabama. No wonder my father was so into it. As a kid, I just assumed the Razorbacks’ reign near the top of college football would go on forever and prove as immutable as my parents’ love. But what the hell does a third-grader know?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Blant Hurt is a graduate of the University of Arkansas and lives in Jonesboro. “Not the Seasons I Expected” is his third book. He is also the author of “The Awkward Ozarker,” a memoir, and “Healer’s Twilight,” a novel. Visit www.blanthurt.com to purchase his works.