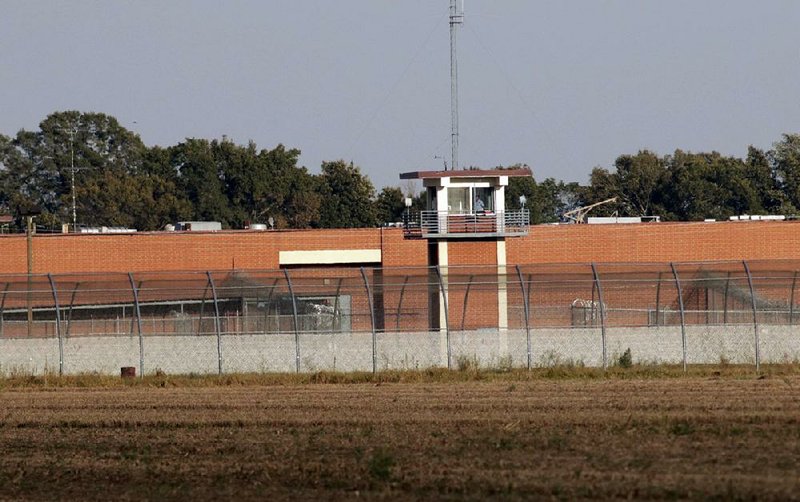

When Patricia Daniel walked into the Delta Regional Unit prison in Dermott earlier this month, it had been nearly two years since she last saw her son face to face.

Her arrest on drug charges in early 2019 left Daniel unable to visit the prison where her son, Greg, is serving a 20-year sentence. After months of working to resolve her case through drug court, Daniel said she was finally approved to see her son earlier this year, only to be cut off again when the Department of Corrections shut down visitation in response to the emerging coronavirus pandemic.

Daniel waited and kept in contact with her son through phone calls, sometimes speaking three or four times a day, she said.

Then, earlier this month, the department announced plans to reopen family visitation through pilot programs at four prisons, including the Delta Unit. Under modified rules published by the prison system, visits were limited to two adults from a prisoner's immediate family, who could meet for one hour while divided by a plastic-glass barrier.

Touching or hugging was expressly forbidden and violators risked losing their visitation privileges for a year, according to the department's rules.

[CORONAVIRUS: Click here for our complete coverage » arkansasonline.com/coronavirus]

Daniel applied for a visit and was accepted the next day, she said.

"I wouldn't change it for the world," Daniel said. "I was just glad to get to see him. I think it was a great experience and I think all people should be able to spend time with their families, especially during the holidays. I think it makes a significant difference in everybody's lives, especially the prisoners. I know my son was very happy to see me."

After a nine-month hiatus in all visitations this year, Daniel was one of 56 families who booked a visit this month through the pilot program that began Dec. 12, according to a spokeswoman. As the holidays approached, Arkansas was one of nine states allowing families to visit prisoners under modified conditions, according to the Marshall Project. The Marshall Project is an online publication that focuses on prison issues, according to its website.

In addition to the Delta Unit, the pilot visitations are being conducted at the Benton Unit, the Northeast Arkansas Community Corrections Center and the Northwest Arkansas Community Corrections Center. The latter two facilities house parole and probation violators. Legal visits remain suspended at all units.

Visitors are not required to be tested for the coronavirus ahead of time, though they are screened for temperature and symptoms upon arrival at the unit. Any visitor who starts showing symptoms within three days of a visit -- or is informed of a close contact before the visit -- is required to notify prison officials immediately, according to the rules.

Despite the halt on visitations this year, the coronavirus infected more than 10,000 prisoners and staff members at more than a dozen units, killing 50 prisoners along with two staff members.

Plans to resume visitation in October were scuttled by rising case counts. The pilot program began this month as infections continued to spread through the prison system.

As of the latest report released by the state Health Department on Dec. 21, 10 prisons and community correction centers reported new infections in the past two weeks. Two, the Benton Unit and Northwest Arkansas Community Corrections Center, reported new positives on Dec. 18, after resuming visitation.

INFECTION CONCERNS

Cindy Murphy, a spokeswoman for the Corrections Department, said no new positive cases have been linked to family visits. The positive cases at the Benton and Northwest Arkansas facilities occurred in barracks that are under quarantine, making them ineligible for the pilot program, she said.

Still, other family members who spoke to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette said they remained wary of the possibility of catching the virus or taking it into the prisons and setting off another deadly outbreak.

"It scares you more walking into a facility knowing that covid is there and you're taking a big risk," said Jenny Morse, the wife of a prisoner serving a 20-year sentence. "I mean, I wear my mask, but still I won't go to that facility to see my husband until I know that it's covid-free. Until every single inmate is covid-free, I won't walk in one."

Morse, a hairdresser, said she has avoided contracting the virus despite her regular interactions with the public through her job. Her husband, she said, contracted the virus during an outbreak at the Barbara Ester Unit earlier this year, but recovered.

Marge Teal, the 73-year-old mother of a prisoner at the East Arkansas Regional Unit, said concerns about her own health after a diagnosis of lung cancer three years ago, combined with the limitations placed on visits, would dissuade her from visiting her son, even if the pilot program were expanded to his unit. She last saw her son in March.

"At the rate they're going now, they're only allowing you to visit for one hour, and it's behind a Plexiglass screen. I can't touch him, I can't hug him," said Teal, whose son is serving a 180-year sentence. "It takes us about three hours to get there and then three hours to come home. And if I'm only going to get to see him under such limited regulations, then I should stay at home."

Like Morse, Teal said her son tested positive for the virus earlier this year and recovered. Both women asked the Democrat-Gazette not to print their loved ones' names, for fear of retaliation.

Murphy, the department's spokeswoman, said the number of family members signing up for visitation was below what the department expected when it created the pilot program.

"We have been hearing from the offenders that as much as they want to see their loved ones, they don't want to risk exposing them," Murphy said.

When Daniel went to visit her son, Greg, at the Delta Unit on Dec. 12, she said she was one of about 10 families who showed up, spread out across a visitation room the size of a small cafeteria.

"I think it was great, everyone seemed happy and everybody was talking and everybody seemed fine," Daniel said. "We had a couple of guards and there was no problems there while I was there. Everybody was thrilled just to be there to see their family."

POSSIBLE JANUARY EXPANSION

Murphy also described the pilot program as a success, adding that the new appointment system used to schedule visits could be continued at some units even after the pandemic. For now, she said prison officials will wait until January to determine whether to expand visitation to other units.

The prison system has taken other steps to aid families in keeping in contact with their loved ones, by cutting connection fees on phone calls as well as reducing the costs of video visitation.

A 10-minute phone call that once cost $4.20 now costs $1.20 and mothers like Teal -- who calls her son daily -- said she felt "blessed" to be able to afford the interactions.

"I can talk to him longer at a time and my money goes further," Teal said. "But not everyone is blessed that way. It's very difficult for loved ones to not be able to see them and visit with them and hug them, touch them, you know and make sure they're OK. It's just, it's very difficult."

For the Christmas they will have to spend apart, Teal said she ordered her son two care packages -- one filled with extra food that he can keep by his bunk and the other filled with toiletries such as toothpaste and soap -- along with a pair of dictionaries that he requested.

Once during the six years her son has been in prison, Teal said that visitation fell on Christmas Day, but she otherwise said "it's terrible" for the families of prisoners and their families during the holidays.

"I'm sure it's very difficult for them," Teal said. "It's just heartbreaking for me."

Morse, who has not seen her husband since February, said that while the pandemic only has worsened feelings of disconnection for loved ones separated by prison walls, it also has given others greater empathy for the experience.

"Horrible is the only word I can use," Morse said. "I told a girlfriend of mine the other day, I said, 'People are finally getting it, so to speak, of what it's like having somebody incarcerated.' When they're complaining about [how they] can't leave their home, they feel isolated, now they know what it's like for an inmate, they're isolated."