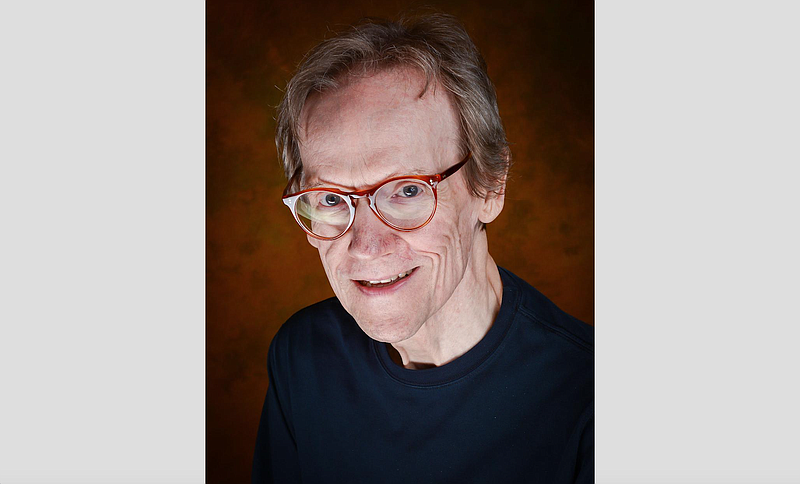

A startling revelation and a stunning cataclysm have buffeted J. Chester Johnson's life of bountiful achievements. They've also helped bring the creativity of this polymath to fuller flower as an acclaimed writer of poetry and prose.

Born in 1944 when Jim Crow still ruled the South, Johnson figured out many decades later that his beloved Arkansas grandfather had joined the white mobs who murdered uncounted Black people during the 1919 Elaine Massacre.

At work on Sept.11, 2001, at his financial firm in New York, he was shaken to the core (almost literally) by the apocalyptic impacts of the two suicide jetliners that toppled the World Trade Center towers next door.

Now, he's an author of some renown, with more than a dozen published books. The most notable include "Auden, the Psalms, and Me," "St. Paul's Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems" and "Now and Then: Selected Longer Poems."

His most recent volume is this year's "Damaged Heritage," a partly personal prose account of the evolving legacy from the massacre 101 years ago in Phillips County. While some of the book is laced with pain, a hopeful message resides in the subtitle's promise: "a story of reconciliation."

Most of his books feature poetry, in a spectrum of topics and tones. What North Carolina poet Melinda Thomsen finds compelling about his writing "is how he digs so deeply into his Arkansas roots. In my review of 'Damaged Heritage,' I focused on not only the book's steps toward reconciliation but also on Chester's precise vocabulary."

Johnson views poetry, including his 2019 Elaine Massacre memorial verse printed at the end of "Damaged Heritage," as a reflection of "personal experiences. It's one of those qualities, ingrained by life or birth or both, that cause a poet naturally to reflect in writing what he or she has actually and individually known."

He quotes the poet W.H. Auden, his predecessor in preparing a fresh translation of the Book of Psalms four decades ago, "as having said that the only book a poet never needs to write is her or his autobiography -- for the autobiography is in the poems."

Along with his parents and older brother, toddler Johnson was living in the Drew County hamlet of Wilmar when his father died of cancer. From age 2 to 5, he stayed in Little Rock with grandparents Lonnie and Hattie Birch.

Lonnie, now known to have taken part in the Elaine Massacre, "was singularly the most important person in my life back then. I remember sitting in his lap on the front porch. I remember our walks, although I normally pedaled my little metallic airplane. I adored him and he adored me. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage just after my mother moved us to Monticello."

New to Monticello, Johnson remembers having developed "close friendships with African-American playmates in a field directly behind our house on the wrong side of the tracks. But when one of us needed to go to the bathroom or get something to eat, we went our separate ways."

As he progressed through grade school, Johnson became an avid patron of the local library, exploring the wider world. By age 14, he was precocious enough to get appointed as a Congressional page by U.S. Rep. W.F. Norrell. He remembers it as "unbelievable, a wonderful experience for a ninth-grader. I lived in a Washington boarding house with 16 other pages. I was the youngest."

The summer after graduating from Monticello High School, Johnson started at fullback for the East team in the 1962 Arkansas All-Star Football Game. He'd served as president of his junior and senior classes as well as the student council. At Boys State, he was one of two Arkansans elected to attend Boys Nation. He also began writing poetry in a serious way.

Admitted to prestigious Harvard College, he headed to New England and a very different world. He aimed to play Ivy League football his sophomore year. That hope ended at a pre-season practice, "when a very bad concussion led a neurosurgeon to forbid me from ever playing football again."

A CIVIL RIGHTS EDUCATION

While studying at Harvard summer school under psychologist and philosopher Rollo May in 1964, he grew ever more curious about the blossoming civil rights movement. After what became known as "Freedom Summer," he left college.

As described in "Damaged Heritage," for three and a half years he traveled through the South in a Plymouth Valiant bought by his mother, Gladys Opal Johnson. Along with seeking to understand what he calls "the racial revolution" and working a couple of jobs, he attended the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville until earning his bachelor's degree.

"I now conclude that this period constituted one of the most, if not the most, important and formative times of my life," he writes in his new book. "While it was painful and uncertain, to be sure, I learned about individual and societal adaptation and reconciliation and forces affecting racial accord that I might not have acquired in any other way."

He then went to New York and deployed his college education to work at Dun & Bradstreet/Moody's Investors Service. For the 1969-70 school year, he returned to his boyhood town. He was one of two white teachers at Drew School, where Johnson taught Black junior-high and high-school students in still segregated Monticello.

In "Damaged Heritage," he remembers the year as challenging and enlightening. He aimed for at least a glimmer of mutual understanding with his Black students: "We were trying, undoubtedly trying, and in our own manner succeeding, though we didn't know it or say so."

During his year in Monticello, Johnson ran unsuccessfully for mayor. Then, he writes, "Monticello had had enough of J. Chester Johnson, and I guess I had had enough of Monticello. ... For all practical purposes, I had forsworn being a white Southerner burdened with its persona from a damaged heritage."

Back in New York, he worked at J.P. Morgan for several years. Asked about the novelty of parlaying finance and poetry, he asserts:

"It's not so unusual. Wallace Stevens spent his whole working life at Hartford Insurance while writing poetry most every day or evening. T.S. Eliot wrote "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" and "The Wasteland" while working at Lloyd's Bank of London. There are other examples. I'm just one in a long chain of such creatures."

His adept work in 1975-76 with J.P. Morgan helping stave off bankruptcy for New York City led to appointment in 1977 as a deputy assistant secretary for the U.S. Treasury Department in President Jimmy Carter's administration.

After leaving the federal position, he started his own company early in 1979. Government Finance Associates Inc. supplied independent advice on debt management and capital financing for state and local governments as well as public authorities.

RE-TRANSLATING THE PSALMS

Earlier a Methodist, he became an Episcopalian in the 1970s. His literary acumen came to the fore in 1971 when he joined the drafting committee doing a re-translation of the Biblical Psalms for the Episcopal Church's 16th-century "Book of Common Prayer."

He served as a poet on the committee, which completed its work in 1979. He replaced W.H. Auden on the project. He tells that story in "Auden, The Psalms and Me," published in 2017.

During the 1970s, he became professional friends with his future wife, now Freda Johnson. Also a financial analyst, she wed him in 1989 -- the second marriage for both of them. They have two children and two grandchildren.

After being a department head at Moody's Investment Services for a dozen years, Freda joined Chester's firm in 1990, with he as chairman and she as president. They were at work on Sept. 11, 2001, in their 16th-floor offices at the western end of Wall Street, only some 150 yards from the World Trade Center's South Tower. Chester still has vivid memories, digested here for space:

"I was on the phone about 8:40 a.m. working on a transaction when we felt something significant that shook our building. That was the North Tower being hit. I stopped the call. All of us were mute and stunned.

"Soon thereafter, Freda looked out the window and saw a plane flying very low. Almost immediately, she saw it hit the South Tower, the one closer to us. We didn't know what to do, so I went downstairs to talk to security. The New York police ordered everyone to stay in their buildings. So I went back to the 16th floor.

"After a little while, both Freda and I were looking at the South Tower when it began to disintegrate. The very dark, massive plume came directly at us. I thought it was the end -- we did not know what was inside the plume. Nothing crashed through our windows, but everything outside went dark like midnight. Very soon, the North Tower also fell."

After several more hours, the Johnsons were able to go outdoors, wearing dust masks they happened to have in a desk drawer. They walked down the 16 floors and onto the street, as he remembers:

"The debris was strewn six to eight inches deep all up and down Wall Street. We walked north much of the way home, a number of miles. No one was talking. Some people were going in our direction, some walking toward the towers, but no one was saying a word."

A FULL FOCUS ON 9/11

Ten days later, the Johnsons were allowed back in their offices, where almost everything had been contaminated. He "could not stop talking about 9/11 and never stopped watching TV about it, but Freda wanted silence. Finally, she sat me down and told me I was driving her crazy -- and that I had to do something."

That spurred Johnson to volunteer at St. Paul's Chapel, which became a refuge for workers combing through the nearby twin towers for human remains. The chapel is owned and operated by Trinity Church Wall Street. His volunteering for months in the polluted air led to serious respiratory problems.

"But I'm not sorry I volunteered," he says. His efforts inspired a poem that has become a widely circulated token of St. Paul's Chapel's role as a refuge for post-9/11 workers. He remembers what shaped his writing:

"I volunteered from 8 p.m. Saturdays to 8 a.m. Sundays. Often, the recovery workers would come in to rest and sleep in the pews. There was a holiness that permeated the chapel 24/7 for eight months. We provided hot food, hand warmers, a place to rest, medicines, foot massages, ears to hear the stories from the Pile, and lots of love."

Johnson began writing his four-stanza poem in February 2002 and released it early that summer. When the chapel reopened to the public on Sept. 11, 2002, the poem was one of eight exhibits. Reprinted on a memento card and powered by a simple refrain -- "It stood" -- the work has been distributed to at least 1.5 million St. Paul's visitors. It is printed in his "St. Paul's Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems."

On the afternoon of each 9/11 anniversary, Johnson reads the poem at St. Paul's, although this year's presentation was done virtually. He professes to cherish the chapel:

"I have told Freda and others on more than one occasion, 'When I'm on the verge of moving on to the next life, please try to get me to St. Paul's Chapel. That's where I want to die.' And I have meant it completely."

REVISITING THE SOUTH

In 2008, Johnson agreed to write the "Litany of Offense for a National Day of Repentance," when the Episcopal Church formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related sins.

While researching, he turned his thoughts to the Delta when he discovered "The Arkansas Race Riot," a 1920 essay by Black activist Ida B. Wells about the Elaine Massacre.

When he was a boy, his mother had mentioned a "well-known race riot" in the Arkansas Delta -- and added that Grandfather Lonnie had played a part. But no specifics had been given.

Reading Wells' treatise so many years later led him to believe this may have been the atrocity in which Lonnie had taken part. More research over several years convinced him that the event his mother had been talking about indeed was the Elaine Massacre

In 2014, he met Sheila L. Walker, a descendant of several massacre victims. They forged a close friendship that has strengthened as they worked with many others toward the goal of racial reconciliation.

In the foreword to "Damaged Heritage," Walker reports that she and Johnson talked for more than two hours on the telephone before meeting in person. When they met face to face, "instead of a handshake, we embraced like old friends. Kindred spirits. Our conversation was honest and frank."

Walker now speaks of Johnson as "a man who doesn't brag. I've learned pretty much everything I know not from him, but either through his writing or from someone else. I say, 'How come you never told me that?'"

"Damaged Heritage" was completed before this year's minority deaths due to police excesses, which galvanized the Black Lives Matter movement. Johnson, 76, says that he now probably would add some thoughts about the acceleration of Black activism:

"I would emphasize that white attention to Black liberation issues ebbs and flows -- a function of how Blacks and whites exist too much in their respective silos. Only when treatment of Blacks seems especially egregious do whites break out of their silo, and then only for a while.

"That's why I'm such a proponent for personal, one-on-one relationships between whites and Blacks, such as the one between Sheila Walker and me. The time is ripe for people of good will -- Black and white -- to break out of those silos and institutional lethargies to achieve person-to-person friendships with mutual commitments to equality in all its forms."

Johnson played a notable role last year on Sept. 29 when the somber Elaine Massacre Memorial was dedicated in Helena-West Helena. He read a poem he'd written for the 100th-anniversary occasion. Like many of his poems, "On Dedicating the Elaine Massacre Memorial" is brief and to the point. Among its 42 short lines, this message rings totally true:

All history is a struggle

Between what we must end

And what we must begin.