NEW YORK — If photography is to retain the high cultural standing it won for itself in the 20th century, we probably want less of it, not more.

There's no chance of that happening, of course. But the problem facing the medium today is undoubtedly acute. Diminished in the digital age by its staggering ubiquity, photography also has been rendered untrustworthy, its once precious relationship to reality sabotaged by the limitless possibilities of digital manipulation.

To counter the medium's rolling collapse into banality, gallery presentations of photographs have lately tended toward smaller, more discriminating selections (solo shows rather than big group surveys), magnified prints (size signals prestige) and a renewed fascination with the medium's 19th-century beginnings.

"The New Woman Behind the Camera" bucks all of these trends — which may help explain why everyone is talking about it. It's a big, baggy show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, through Oct. 3, that's scheduled to open at the National Gallery of Art on Oct. 31. Conceived and organized by the NGA's Andrea Nelson with the assistance of the Met's Mia Fineman, it presents about 200 photographs by 120 female photographers from more than 20 countries.

The selection criteria are almost laughably loose: The curators have opened their arms to a variety of genres, including fashion, advertising and propaganda, as well as portraiture, reportage, nudes and avant-garde experimentation. And yet the show's cumulative impact is revelatory.

LADIES DAY

The photographs were taken between 1920 and 1960, all of them by women. Some are well known: Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, Lee Miller, Leni Riefenstahl, Tina Modotti, Lisette Model, Dora Maar, Helen Levitt, Imogen Cunningham, Claude Cahun, Ilse Bing, Lola Alvarez Bravo and Berenice Abbott are all canonical 20th-century photographers. But that leaves more than 100 photographers I'd never heard of.

A sizable majority are from Europe and the United States, where the post-World War I notion of the "New Woman" — liberated, empowered, mobile — held greater sway. But the "New Woman" concept caught on elsewhere, too, so there are works by photographers from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, India, Israel, Japan, Mexico and the former Soviet Union.

Women such as Julia Margaret Cameron and Anna Atkins contributed profoundly to the development of 19th-century photography, but it wasn't until the 1920s, Nelson argues, that they "entered the field in force." In some cases, their careers were cut short either by marriage and child-rearing or political exile and war. Many were neglected by the art world because they worked in fashion or journalism rather than self-consciously as "artists" (a problem not unique to women). More still were ignored by critics and curators who minimized women's contributions.

So the show is a corrective: an attempt to recover the work of female photographers (at which it succeeds, brilliantly) and to open the door to what Nelson calls "a sustained and rigorous examination of their careers on a par with those of their male counterparts" (which it knowingly leaves for others to do).

BERENICE ABBOTT

Berenice Abbott is one whose reputation didn't need recovering. Yet it's always salutary to be reminded of her work's preternatural assurance. Abbott established her own photographic studio in Paris before she turned 30. As with Lee Miller and Marianne Breslauer, two other stars of the show, she learned from Man Ray. And like the gender-bending Claude Cahun, she was a lesbian. (Abbott's partner was the art critic Elizabeth McCausland.)

In Paris, Abbott became known for portraits of leading cultural figures, including James Joyce and Janet Flanner, and for championing the work of the then little-known Eugene Atget. Atget's hauntingly empty streetscapes inspired Abbott to photograph New York in a similar mode. Her 1935 photograph "Vanderbilt Avenue From East 46th Street" approaches perfection. Raking light and a vertical zip of sky open up the claustrophobia of the city to distant dreams.

Photography tends to communicate "there and then" in contrast to painting's "here and now." But occasionally a photograph has such immediacy that you feel its subject burst out of its envelope of past time, like an extravagantly petaled flower exploding out of the tight folds of its bud. Annelise Kretschmer's portrait of a young woman is just such a photograph.

Kretschmer exhibited regularly with the Society of German Photographers in Dresden. On a trip to Paris in 1928, she sought, like Abbott, to capture the modern city, photographing effects of light on buildings and pedestrians. Back in Germany, she opened a studio. But her father was Jewish, and life under the Nazis became increasingly untenable. Ousted from the Society of German Photographers, she endured as her studio was repeatedly vandalized and later bombed.

World events were an ominously advancing backdrop to the creation of all of these works. You can feel their pressure encouraging the photographers to look at people with renewed wonder, stripped of outmoded indicators of social standing, vibrant with the static of society's wider convulsions. A 1931 photograph of a young circus performer in Berlin by Marianne Breslauer, another German, is a superb example, simultaneously conveying untethered social status and electrifying self-possession.

CLAUDE CAHUN

Just as memorable is a famous self-portrait by Cahun. Collaborating with Marcel Moore, who was not only her lover but also her stepsister, Cahun staged riveting self-portraits — in this case, doubled by a mirror — that have influenced everyone from David Bowie to Cindy Sherman. Cahun — who dismissed gender categories ("Masculine? Feminine?" she wrote. "It depends on the situation.") — moved with Moore to Jersey, in the English Channel, in 1937. When the Nazis occupied the island, the two organized their own risky resistance. For their troubles, they were arrested and sentenced to death. They were saved only when the island was liberated in 1945.

Lee Miller and Margaret Bourke-White were among a number of female photographers who were also war correspondents. Bourke-White worked for Life, Miller for Vogue. Both photographed Nazi concentration camps after they were liberated. With mud from Dachau still on her boots, Miller was photographed in Adolf Hitler's bath in Munich — on the same day that, unbeknown to her, he committed suicide. She slept in his bed that night. An astonishing photograph she took at Buchenwald shows liberated prisoners applying the final touches (a swastika drawn on the sleeve) to an effigy of Hitler just before hanging it. Watching on, the ex-prisoners smile softly. Their relaxed stances defeat the mind's capacity for comprehension.

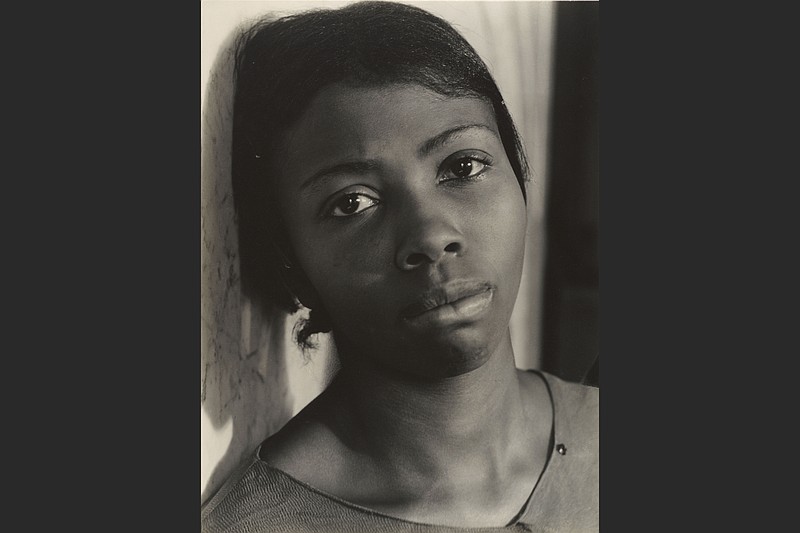

I found myself spellbound by the studio portraits of Karimeh Abbud, the first professional photographer in Palestine, and by the more informal portraits of Consuelo Kanaga. Kanaga began her career as a staff photographer at the San Francisco Chronicle, and, after getting to know Dorothea Lange, Tina Modotti and Edward Weston, she took to photographing the disenfranchised. Her close-up of Annie Mae Merriweather, a young Black girl who leans her head against a wall, exerts an extraordinary magnetic pull, encouraging the kind of long, privileged gaze that real-life encounters tend to bar. Merriweather's expression is patient, almost pitying, but ultimately unknown.

ACCUMULATING UNKNOWNS

Photography promises the power of witness, the authority of evidence, but around any given photograph, it's usually the accumulating unknowns that keep us hypnotized. I was drawn to the absence of information around Anna Barna, a Hungarian photographer represented here by a captivating portrait of a boy balancing on the back of a chair as he peers over a high wall. We can't see what the boy can see — the wall obstructs us. But by the same token, we can see what he can't: a fold in his jacket casts a shadow on the wall shaped like a sharp-nosed face in profile.

But who was Barna? One hundred of her photographs were found among the belongings of Andre Kertesz in 1983, two years before the great photographer's death. Kertesz had taken a photograph of Barna in Paris in 1935. Ten years later, Barna moved to New York, where she took photographs of the streets and the towering cityscape. But beyond that, little is known.

Not yet, anyway.

FASHION PHOTOGRAPHY

Some of the fashion work in the show is breathtaking. For sheer eye-rinsing elegance, nothing beats Lillian Bassman's "Translucent Hat," from about 1950. But I was just as drawn to the gauche, anti-classical energy in a photograph of the avant-garde dancer Gret Palucca. It was taken by Germany's Charlotte Rudolph, who pioneered dance photography in the 1920s.

A revealing image by Frances McLaughlin is the most high-spirited in a wonderful series of portraits — most of them self-portraits — that break the fourth wall, so to speak, by showing photographers at work. McLaughlin captures Toni Frissell photographing three fashion models posing in front of a makeshift outdoor set. In the foreground, Frissell's daughter plays with her husband, who reclines on his back in the grass.

It's a happy, smiling, beautifully textured photo. But something about the situation — Mom at work; Dad temporarily picking up the slack with the kids (although with minimal effort); art indentured to commerce; a clean, contrived image in tension with a messy, complex reality — feels uncannily familiar. Seeing it, I thought of all the labor and creativity that women put into keeping the show — the whole show — running, and of how rarely we see this depicted.

"The New Woman Behind the Camera." Through Oct. 3 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; metmuseum.org. Oct. 31-Jan. 30 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington; nga.gov.