Editor’s note: This is Part 1 in a series about Tom Slaughter's historic 1921 escape from the Arkansas state prison known as The Walls. Part 1 appeared in Style on Dec. 13, Part 2 on Dec. 20, Part 3 Dec. 27. See arkansasonline.com/1227part1 and arkansasonline.com/1227part2 and arkansasonline.com/1227part3

See arkansasonline.com/1227men for information about the seven escapees.

See arkansasonline.com/1227hogg to read what the minister said at his funeral.

■ ■ ■

Late on an almost-winter afternoon, alone in an open expanse of Oakland Fraternal Cemetery with the shush of interstate traffic in the distance, it’s hard to imagine what happened here 100 years ago today.

But close your eyes and imagine thousands of eager gawkers crowding around, pressing in, being shoved back by uniformed policemen.

Instead of these little green weeds in the faded lawn, picture a jostling throng dressed the way Arkansans did in 1921: the hats, the heavy leather boots, the long skirts and button-up shoes. Look down from on high and see, smack in the center of the scene, a rectangular hole in the ground surrounded by a rope cordon, surrounded by a sea of people.

On Dec. 13, 1921, more than 5,000 spectators filled this cemetery to witness a murderer’s burial. The gently rolling hillside was already packed an hour before the cortege arrived from the Healey & Roth chapel in town — where another estimated thousand had crowded the street since dawn, trying to see or hear the funeral of Tom Slaughter, the state’s most conspicuous criminal.

The multitude was “morbidly curious,” the Arkansas Gazette reported the next day:

“Patiently they waited in the sun, men, women and children; mothers with wailing babies in arms, withered widows in their declining years, flappers engaged in direct and indirect flirtatious conquest, small boys at target practice with pebbles on the nearby headstones, opinionated men voicing the belief the bandit was still at large, since nothing in the newspapers is to be believed.”

Every so often a volunteer mob-handler climbed atop a grave stone and from that vantage point announced the nonappearance of the funeral cortege. It finally arrived about 3:30 p.m. A car crammed with wilting roses and lilies came first, including a mysterious $200 array that persons unknown ordered from a florist in Benton.

So many people filled Oakland’s dirt lanes that few actually saw the black casket unloaded and carried to its bier.

Today, a 6-inch post with a sign bearing a number for a cell phone tour and “Stop #34” calls attention to a battered stone stump. It looks like nothing man-made — just a small outcrop — but according to the cemetery’s information, this is what’s left of the grave marker of Tom Slaughter, outrageous bad man.

Souvenir hunters chipped off the rest.

CAGEY CRIMINAL

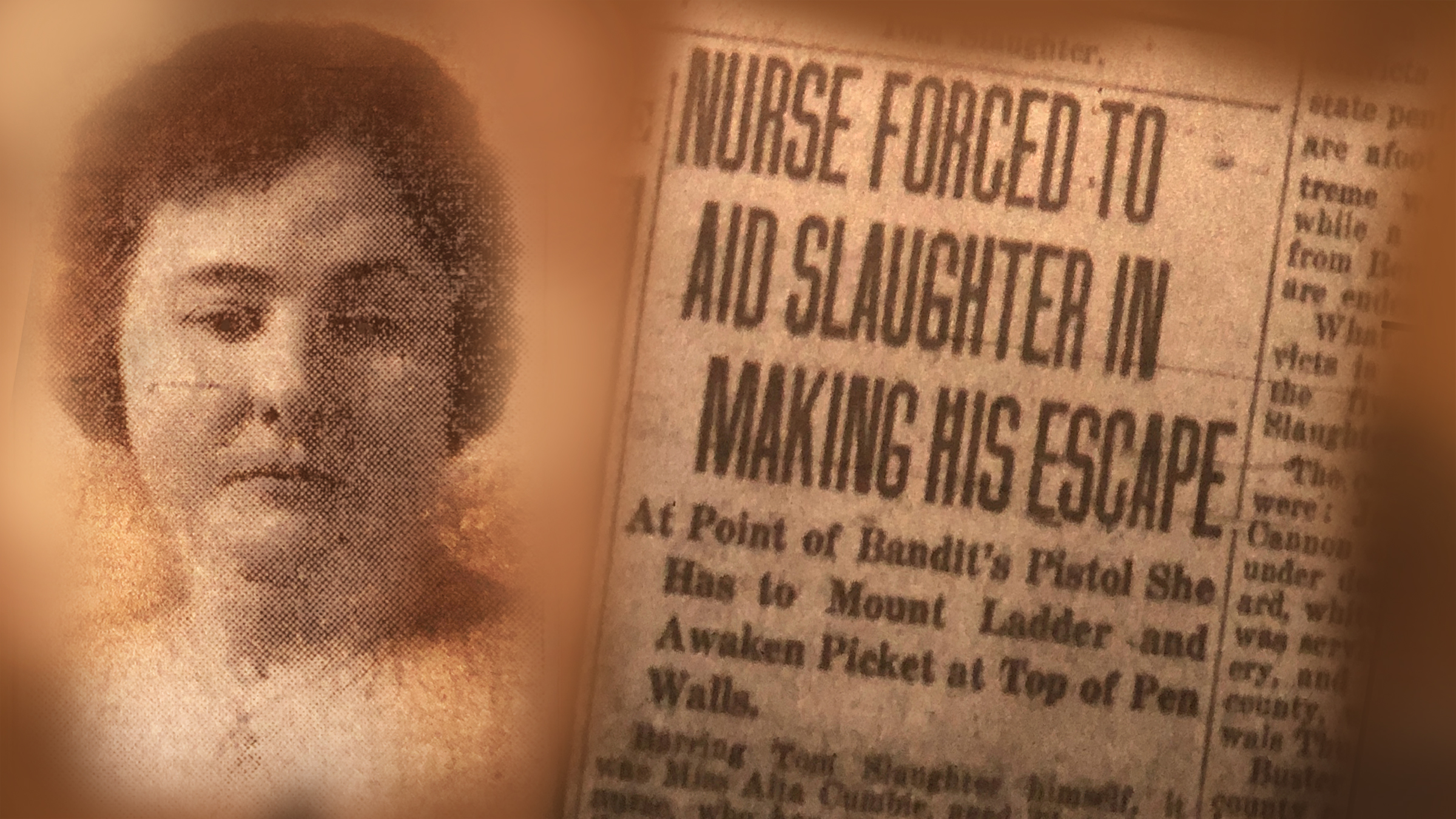

Born in 1896 at Bernice, La., the big, good-looking ladies man called “Curley” Slaughter packed a lot of heavily reported crime into his 24 years. A decade of robberies, gangs, incarcerations, weddings, escapes and killings started modestly in 1911 with the theft of a cow in Pope County.

Convicted of murder in Arkansas, he and a pal, Fulton “Kid” Green, also were wanted in Pennsylvania for killing a bank cashier.

He and his gangs stole cars, knocked over banks and trains and, apparently, made fans in Kentucky, Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas. This man was notorious for creative escapes. Slaughter escaped from jails and prisons in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Arkansas.

The second time he broke out of the Texas state penitentiary, he simply walked out of its hospital: He had pricked himself all over with a pin, poured croton oil on his wounds to create a rash and then eaten two bars of soap. Thinking he had smallpox, jailers left him alone in sickbay.

During his trials in Arkansas, the governor sent out the National Guard twice to block escape attempts rumored to be afoot among Slaughter’s unseen cadre of criminal friends.

Slaughter also became a cause celebre for Arkansans concerned about the abuse of prisoners on the state penal farms. He was whipped and humiliated by Warden Dee Horton. Famously, Slaughter converted to Christianity there, and was baptised by the Rev. W.B. Hogg of Winfield Memorial Methodist Church.

Hogg lost faith in him when he learned Slaughter had three wives.

But what really gripped the public imagination were the events of Slaughter’s final 48 hours of life.

PRISON AT HIS FEET

On the evening of Dec. 8, 1921, Slaughter lay in apparent pain in a death cell at The Walls, the Arkansas state penitentiary at Little Rock. He was condemned to die for the murder of Bliss Adkisson, a Tucker Prison Farm trusty whom Slaughter shot while failing to escape, not long after his Christian conversion.

From contemporary accounts in the Gazette and the Arkansas Democrat; three 1953 essays by Gazette crime reporter Joe Wirges, who covered Slaughter in 1921; a 1960 Democrat interview with a former Saline County sheriff; and the “Tom Slaughter (1896–1921)” entry in the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas, here’s some of what happened that day inside The Walls:

On or before Dec. 8, a Thursday, prisoner Slaughter somehow acquired a German Luger pistol. He had been feigning illness for some time, saying he was too weak to talk, as Wirges later recalled.

In the afternoon, Slaughter begged his guards, Herman Vezollie and Tony Coppersmith, to ask “Captain” Dempsey — Warden Elston H. Dempsey — to send him the nurse who was in the prison tending a badly injured bank robber named Orville Reese. Nurse Alta Cumbie determined that Slaughter had a fever.

About 9 p.m., Slaughter begged for a blanket. Vezollie tried to hand the blanket to Slaughter through the bars, but he couldn’t or wouldn’t reach. Breaking prison rules, the guard opened the cell and stepped inside to spread the blanket over the ailing inmate, whereupon Slaughter seized him by the throat and leveled the pistol on Coppersmith.

“Don’t raise your gun, Tony, or I’ll kill you,” he said.

He took Vezollie’s coat and made the two guards walk ahead of him to the foot of stairs leading to the condemned prisoners’ area of the Death House. Slaughter yelled up to the guard on the second floor the customary, “Coming up.”

“Come on,” the guard answered back.

At the top of the stairway, Slaughter made all the guards lie face down. Then he liberated the 12 Black prisoners on the floor, all condemned men. Six were still facing the death penalty as alleged perpetrators of the 1919 Elaine Massacre.

Slaughter invited all these men to escape with him, and five agreed. The Elaine inmates politely declined.

Slaughter singled out Ed Coleman, 81, to join the escape, but Coleman declined. Slaughter then demanded his money, but Coleman only had $6, so Slaughter told him to keep it. And he kissed Coleman on his bald head.

Then with an oath and declaring that he ought to kill them all, he locked up the not-keen-to-escape inmates and the guards. His assistants then helped him capture every guard inside the barracks as well as the yard man, who monitored the grounds outside until midnight.

Wirges, the Gazette reporter, called The Walls several times every night. At 10 p.m., he telephoned the paid guard in the prison’s outside office, Sam Taylor. Taylor said, “Everything’s quiet. Gotta go now, Joe, someone’s knocking at the yard gate.”

That was Slaughter.

THE NURSE

Alta Cumbie, 32, had been a nurse for 11 years, including several as supervisor in the State Hospital for Nervous Disorders, where her life was at risk more than once.

She was heating milk for her patient Reese in the kitchen below the hospital ward when Slaughter swaggered in. “Well, nurse,” he said, “put up your hands.”

“Why, Tom, you wouldn’t hurt me, would you?” she asked.

“No, but you are going to do what I tell you to,” he said. “Come on. We are going over to wake Dempsey up.”

She talked him out of that, fearing she’d be shot by the tower sentries. So, he used her to take out the sentries.

He marched her through the main gate, which was wide open and guarded by his confederates. Tower sentries didn’t come on duty until midnight, but they slept in their towers. Slaughter walked the nurse around the outside of The Walls to the southeast corner of the compound.

“Now, get on up that ladder and wake up the picket,” he ordered. Trembling, she protested that she could not climb the perpendicular, nearly 30-foot ladder; but he aimed the pistol at her, so she did. He followed a few rungs below. Any time she protested that she couldn’t go on, he told her to be quiet.

At the top of the wall, Slaughter pushed her toward the little octagonal tower. Whispering, Cumbie begged him not to make her go in first. But the sentry, a trusty, was asleep. Slaughter had her shake him awake, then took the sentry’s rifle and forced them to climb down the ladder ahead of him. Slaughter locked up the sentry in the cellhouse.

This performance was repeated at the other corners of The Walls, which had steps and so the hazard was less as far as the nurse was concerned.

HELLO, WARDEN

With Taylor locked up, Slaughter, a gun in each hand, told Cumbie to mount the stairs to the warden’s quarters. She meekly obeyed, although she feared Dempsey was aware of the insurrection and would shoot as soon as his door opened. He kept a rifle by his bed.

But the bedroom was dark. Cumbie shook Dempsey and his wife awake, saying, “This is the nurse.” She had brought him updates about her patient Reese a few times, so it took the couple a few beats to realize that Slaughter was standing at the foot of the bed.

“It’s Tom,” he drawled. “Get up and dress and come with me.”

Cumbie, meanwhile, roused the warden’s children: Mrs. Laura Pitman, 22, in whose room a light was burning; daughter Ventura, 19, who was reading in bed; and Edward, a high school student, who was on the sleeping porch. Pitman’s 15-month-old daughter was with her.

The children rushed into their parents’ room, which was dimly illuminated by a light from a bathroom across the hall. Slaughter grimly stood in the dark, while the warden and his wife tried to dress.

“Don’t you kids worry about your Daddy,” Slaughter said coolly. “I would not harm a hair on his head. He has treated me too square while I have been here.”

Slaughter herded the partly clad family across the yard and locked them in the death cells, the warden in one and his family in the other. Slaughter took Pitman’s toddler in his arms and kissed her head. He promised not to harm the family.

ENJOYED HIS REIGN

Still compelling Cumbie to accompany him, the bandit proceeded from one part of the yard to another, awakening prisoners in the hospital, the tailor shop and other buildings where trusties slept.

He snipped telephone wires and took the tires off all the vehicles at The Walls except those on a large touring Ford used by the warden’s wife. That car he packed with the tires and with guns.

He played pranks on trusties he disliked. Shouting, “Run you [blankety-blank], or I’ll shoot you full of holes,” he made one man run in circles with his hands above his head. He made another dance a jig.

Slaughter and his companions selected civilian clothes in the prison commissary; he commandeered young Edward Dempsey’s shoes.

He took Cumbie back to the kitchen and procured cold coffee, canned milk, bread and canned goods, which he handed to the warden and his family, through the bars, so they wouldn’t go hungry before they got out.

He took a bottle of milk to Cumbie’s patient Reese, wished him the best of luck and shook his hand. Then Slaughter locked Cumbie up, too.

He and six companions piled into the Ford. They included Black inmates Jim Wells, condemned for the murder of a German farmer at Monticello; Jack Buster of Jefferson County, condemned for killing a white man during a robbery; Willis Cannon and Clifton Taylor, from Sevier County, condemned for killing a Black man; and Charles Jones of Pulaski County, who had just arrived at The Walls to begin serving 21 years for wounding a railroad agent. The sixth, James C. Howard, a white man from Garland County, was doing three years for forgery.

The warden’s family heard them drive away at 2:30 a.m. Slaughter locked the big gates on his way out.

Part 2: Four posses hunt Slaughter and his companions in hills above Benton.