Larisa's Shepitko's bleak WWII-era film begins with a shot of a frozen Russian landscape, with the sound of howling wind and distant gunfire in the background: It doesn't get a whole lot more cheery from there. The story is simple enough to be a fable, an allegory, with which the late Shepitko, a veteran Soviet filmmaker born in the Ukraine a few years before the war, painted the entire miserable enterprise.

Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov) and Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukhin), a pair of more or less randomly assigned Russian partisans hiding out with their comrades and families in the woods in a part of German-occupied Russia, are sent out to a nearby farm to procure more provisions for the slowly starving group.

En route to the farm, we learn a bit more about the men: Sotnikov, a former math teacher, seems bound by a moral code of conduct; Rybak, a bit more open and ribald, shares stories of his romances and carousings with some abandon. When they are captured by the Germans, along with Demchikha (Lyudmila Polyakova), the unfortunate woman in whose hay loft they are initially found, they are each drilled into by Portnov (Anatoliy Solonitsyn) a local German sympathizer turned lead interrogator. Sotnikov gives them nothing, and is badly tortured as a result; Rybak tells them what little he does know, and spares himself.

Given a night to themselves, along with a scattering of some other prisoners, including a young Jewish girl, Basya (Viktoriya Goldentul), recently discovered in the village, Sotnikov and Rybak are given the opportunity to face their obligatory executions in their own manner. Typically, the former accepts his fate, and refuses to compromise himself, while his friend is all too eager to consider other possibilities (despite Sotnikov's imploring him to "burden his conscience"), including selling out entirely and joining with the German sympathizers as a member of local police.

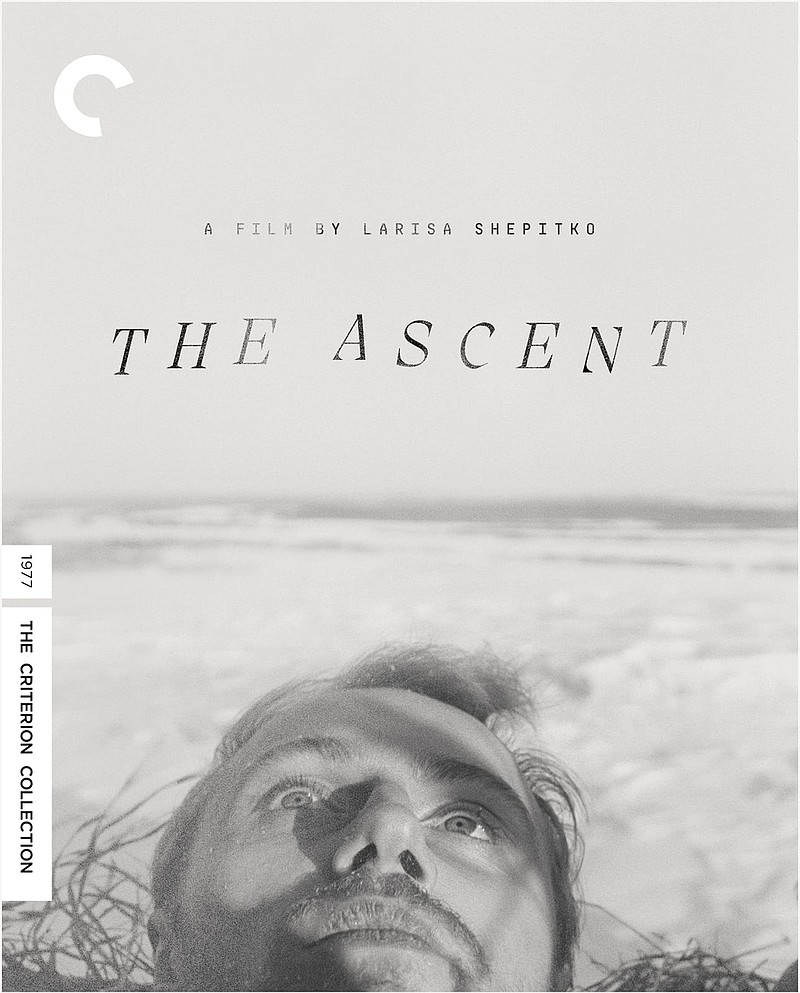

Shot in 1977, Shepitko's film has the essence of a film far older, with its boxy aspect ratio; gray-tinged black and white film stock; and a penchant for camera angles looking up at its subjects in the deifying manner of Dreyer's unforgettable "The Passion of Joan of Arc." In the face of the continued suffering of the era -- the frigid conditions are such that the snowflakes on the men's faces remain for long minutes without melting -- the film suggests the only grace and comfort we can hope to attain comes from the salvation of uncompromise.

When Rybak returns to the German camp, having escaped his fate, the now-open doors of the cellar where he spent the night with the other prisoners gape into blackness, the very gates of hell themselves. Better to burn at the stake, it would seem, than for all eternity thereafter.

Special Features: The new 4K restoration is glorious unto itself, but Criterion also adds a bounty of other goodies, including a new introduction by Shepitko's son, Anton Klimov, an interview with Polyakova, a short film by Shepitko, and another short film about the director after her death, only two years after the making of this film.