Editor’s note: This is Part 3 in a series about Tom Slaughter's historic 1921 escape from the Arkansas state prison known as The Walls. Part 1 appeared in Style on Dec. 13, Part 2 on Dec. 20. See arkansasonline.com/1227part1 and arkansasonline.com/1227part2

See arkansasonline.com/1227men for information about the seven escapees.

See arkansasonline.com/1227hogg to read what minister said over his grave.

■ ■ ■

As the first whrump from James Howard's .45-caliber pistol split the night, Charles Jones jolted awake, tense from head to toe.

Peering around a small stump, he saw Howard in wavering firelight, arm extended. The white man stood about 10 feet in back of and aiming down upon the reclining form of Tom Slaughter.

Jones, by his account, was terrified; and then Howard fired again, several shots in quick succession.

Someone hollered, "Don't shoot any more," and Jones bolted, running, as the Arkansas Gazette quipped, at a remarkable clip for a man with a bullet hole through his hip.

He was unarmed, and so were condemned murderers Jack Buster and Willis Cannon, who also sprinted away. Howard emptied his revolver after them as they crashed over underbrush and fled into the dark hills northwest of Benton.

This all happened about 8:30 p.m. Dec. 9, 1921.

A half-mile away was the farmhouse of Wes James, whose yard dogs had sounded like braying bloodhounds to the fugitives that afternoon. After killing Slaughter, Howard hiked there with his confederates, Clifton Taylor and James Wells, anxious to surrender. The farmer didn't have a phone and refused to leave his house.

They found Steve Ferguson's farm two miles away. He called the sheriff while his neighbor, Earl Gunter, gave the escapees a lift toward Benton. Saline County Sheriff Jehu Crow met them on the way and took them to the jail in town.

There, Wells and Taylor supported Howard's claim of shooting in self-defense. "I had planned that with the aid of Wells and Taylor, we could bring the other four back to The Walls," Howard said, insisting that's the only reason he had joined the escape. After all, he was just doing time for forgery, while all the others except Jones faced death sentences.

"I did not intend to hurt anyone as long as I could keep from it."

Early in the morning Dec. 10, officers returned Howard, Taylor and Wells to The Walls at Little Rock.

A posse of 25 residents of the remote hills had been unable to find the campsite in the dark, and twice that many men did not find it in daylight, either. With roads little more than broad hints over rocks, they fanned out through the woods on foot.

Fearing that Howard's surrender might be yet another ruse by Slaughter, the vaunted escape artist, Crow called Warden E.H. Dempsey at The Walls, and he agreed to send Howard back as a guide. But although Dempsey's son, Edward, drove so fast his car nearly boiled dry on the way, Howard didn't arrive in time to be of use. At 11:05 a.m., the searchers found the bandit's remains.

What they saw convinced them Slaughter died in his sleep. They counted six wounds and noted the position of the body.

On their way to Benton, Dempsey and Howard met the flat-bed Ford bearing the tarp-covered corpse. Everyone got out to pose for a photo with the handcuffed perpetrator, and Slaughter.

MOB SCENE

When the posse reached Benton, Arkansas Democrat reporter Hubert Park watched stores empty as if by magic, their doors left swinging as residents rushed to the Saline County Courthouse square.

A huge crowd blocked the cars at the southwest corner of the square. Crow ordered them back, and two cars were able to advance a block and a half to Benton Furniture & Undertaking Co. at 111 N. Main St., where a perimeter had been roped off.

But people ran for the undertaking shop. "The mob literally filled the street, making the progress of automobiles almost impossible," Park reported.

The car with the body turned down an alley to the back of the shop, while officers blocked the alley entrance.

Everybody wanted to see the body. After a short conference, the officers placed it on a cot on the roped-off sidewalk, with a car in front to restrict access. With much difficulty, they shifted the mass of people so the curious could pass by in pairs.

[Gallery not visible? Click here » arkansasonline.com/1220Tom/]

For about 45 minutes, almost 2,000 men, women and children gawked at a clotted corpse. In the next day's Gazette, reporter Joe Wirges described the wounds in graphic detail, which we won't do here. But the condition of the face didn't quiet doubts about the victim's ID.

COLLATERAL DAMAGE

During the excitement, one of the posse cars collided with a one-horse wagon. The impact tossed the driver under a wheel; the wagon rolled across his chest. The horse dragged the wagon into a lightpost, with a loud crash. And a tire exploded, like a gunshot.

Park saw only about six people leave the crowd to watch the victim get to his feet.

CONSEQUENCES

Although Gov. Thomas McRae at first opined that Howard would have the $500 reward for Slaughter's body, he changed his mind. And the forger, dismayed that a tide of public opinion portrayed him as a cowardly, greedy murderer, wrote to McRae declining any reward.

An inquest at Benton recommended charging Howard with first-degree murder. But on Dec. 13, the Saline County Grand Jury declined to.

Dempsey sent Howard to Tucker Prison Farm, whose warden, Dee Horton, famously despised Slaughter. He gave Howard a relatively cushy job in the tailor shop.

Also Dec. 13, Slaughter was buried at Oakland Fraternal Cemetery in Little Rock during another mob scene (see arkansasonline.com/1227part1). But three of the men he'd freed were still on the lam, and the repercussions of the great escape were only just beginning.

For instance, on Dec. 15, 1921, screams of bloody murder brought teachers rushing out of Pine Street School in Pine Bluff. They found a dozen or more boys chasing a blond kid while shrieking like banshees.

The next day, the district banned the new game "Tom Slaughter." Kids were advised to go back to "Fox in the Morning" (see arkansasonline.com/1227fox).

UN-TRUSTED

Locked into the death cell he'd opened to hand Slaughter a blanket, trusty Herman Vezollie was a rather handsome Italian youth doing three years for bigamy. He had served with the Army in Europe, and he was furloughed just that week to visit his wife in Little Rock.

But Dempsey believed the other guard, Tony Coppersmith, duped Vezollie. Coppersmith had just started a one-year sentence for running a gambling house.

Dempsey stripped both inmates of trusty status and sent them to Tucker Farm.

But the Honorary Penitentiary Commission paroled Horace Hayes, the young auto thief whose heroic exploits gave lawmen the jump on the fugitives. Hayes was a model prisoner, Dempsey said, and probably not so very guilty of auto theft. An unnamed business in Little Rock gave Hayes a job.

James Howard, on the other hand, proved a different model of prisoner. After a few months in the tailor shop he was made a trusty; and in March 1922, during a five-day furlough supposedly to visit family at McGehee, he ordered two guns from a Little Rock hardware store -- by telephone, posing as C.E. Toney, clerk of the Penitentiary Commission. He had the revolvers delivered to him at the Rock Island depot.

He pawned them for $10 each.

He tried the trick again the next day, unaware that a prison official was at the station to transport convicts. Howard arrived right after the store's delivery boy and spun a tale about doing the warden a favor. The officer promised to take the gun directly to Horton himself.

The next day, Howard found himself back on the farm, trusted no more and assigned to hard labor. He wrote an apology to the governor, begging forgiveness, saying he just hadn't been steady in his mind since the whole Slaughter affair.

By this time, his confederates Taylor and Wells had admitted they lied to protect Howard, that Slaughter was asleep when Howard shot him. The Saline County Grand Jury once again declined to indict. Supporters, including a bunch of letter writers in Texas, urged clemency, arguing that Tom Slaughter needed killing.

In October 1922, after Howard became eligible for parole, McRae furloughed him through the end of his sentence, Jan. 1, 1924, to work on his uncle's farm in Howard County. He never was charged with murder.

THE WARDEN

Elston H. Dempsey wasn't merely warden at The Walls. He had been the prison's resident electrician since 1916: state executioner.

According to figures he compiled and that were reported in the Gazette on Jan. 1, 1922, Dempsey electrocuted four prisoners in 1921, with no hitches. The last man he put to death, on Dec. 30, was John Henry Price of Helena, a Black man convicted of killing F.C. Moody, dairyman, during a dispute over wages.

The next day, the Honorary Penitentiary Commission fired Dempsey, and he protested but complied.

Dempsey soon had a new job with the Gay Oil Co., running gas stations at 14th and High streets, then at Seventh and High and then at Third Street and Broadway. In 1926, he was promoted to manage a station at Prospect Avenue and Beech Street in the Heights.

His favorable public standing extended to his wife, who, in 1925, became superintendent of a new orphanage funded by the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, at 4823 Woodlawn Ave.

REPERCUSSIONS

The wounded escapee, Charles Jones, was arrested in Louisiana in March 1922. Later that month, Willis Cannon also was caught, near Ashdown in Little River County.

But Jack Buster was missing for four years. He wasn't free. He was in jail in New Jersey, imprisoned under a different name. Returned to Arkansas, he was electrocuted in 1925, a clockwork execution that lasted all of 20 seconds.

Much more could be said about his case and how the size of the reward McRae was able to offer for his capture was used against the governor in his next gubernatorial campaign. But readers' eyes grow weary. Just one more story before we stop.

JAMES WELLS

So, the penitentiary commission had fired its experienced executioner. When the date set for Clifton Taylor to die arrived, the panel couldn't find an electrician and wasn't willing to pay to hire one from a neighboring state.

Coincidentally, Taylor's trial judge suggested to McRae that, possibly, Taylor was someplace else when the man he and Willis Cannon were convicted of killing was killed. Just in case, McRae commuted Taylor's sentence to life in prison.

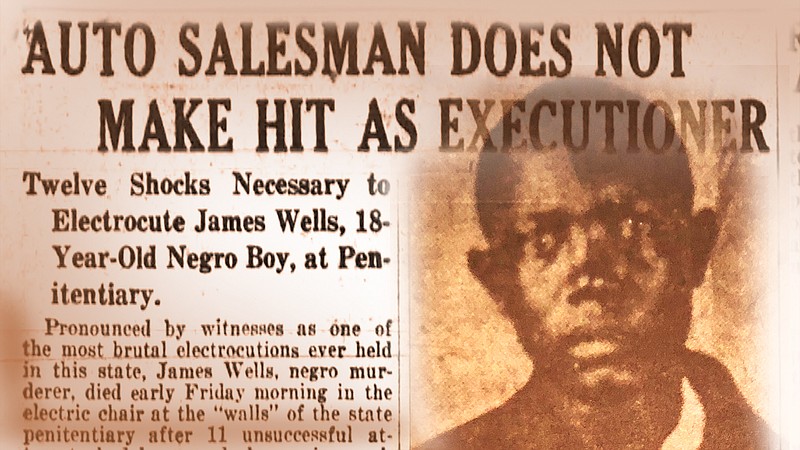

But the panel found a volunteer for the execution of 18-year-old James Wells.

Wells was condemned for the murder of Peter Trenz, a 70-year-old German farmer at Monticello who, it came out at trial, began his last day by berating Wells and his brother, Calvin, calling them lazy. The teens then worked a full day; but that afternoon they showed up in town seeking help because Trenz was dead, bludgeoned. Convicted of second degree murder, Calvin Wells got life in prison.

At the time that James Wells escaped with Slaughter, the state Supreme Court was reviewing an appeal of his death sentence. The court denied that appeal on Christmas Eve 1921.

And so, March 10, 1922, Wells became the first inmate electrocuted in Arkansas after Dempsey's dismissal. A late edition of the Gazette described what happened:

"Going to the chair singing and without assistance, he continued to sing until the first charge of electricity was sent through his body. After the electricity had been allowed to remain on a few moments, it was taken off and Wells was examined by the state physician, who pronounced him still alive."

The executioner threw the switch again. Again Wells survived. After a third jolt, witnesses fled the death room, and the convicts who had strapped him to the chair were sick to their stomachs.

It took amateur executioner C.W. Whayne, a car salesman from Lonoke County, 12 attempts and 20 minutes before the young man died.

Whayne, who claimed a correspondence course in electricity, told the Gazette there was "no element of brutality" in the execution. He blamed the youth and vigor of the young man's body, and the way the prison trusties strapped his legs to the wooden chair.

The Democrat's editorial page denounced the penitentiary commission, saying what happened to Wells was a "horrible and revolting disgrace" and showed that "in following after so-called economy we may reach a condition that is not economy, not decency, not even humanity."

That spring as other execution dates arose, McRae issued stays, one after another. In September, he commuted Willis Cannon's death sentence to life in prison, too.

■ ■ ■

In 1995, retired undertaker John Healey (1910-2007) told this writer about a curious practice at Oakland cemetery. Groundskeepers would periodically scatter little scraps of granite around Slaughter's grave marker, so souvenir hunters would take them and leave the rest of the sad stub alone.

There are such chips in the grass beside Tom Slaughter's stone today.

Gallery: Escape from The Walls