It's not surprising after a year spent pretty much underground, making social contact via screens, and not leaving the confines of your domicile, this year's batch of Sundance films reflects an increased level of alienation, along with a forced sense of having had to look inward for answers.

As can be expected, the results of this collective navel-gazing tended to generate even more questions.

We can start with a film actually shot last summer, during the pandemic itself. Ben Wheatley's "In the Earth" is, as he explained in his Zoom introduction, very much meant to reflect "the politics of the times," and in many ways, he has done just that.

Set sometime in the near future, when an even more deadly plague has hit the planet, the story concerns a scientist named Martin (Joel Fry), meant to travel deep into a boreal forest in order to make contact with a colleague at her research station in the bush. Taking him on the two-day journey is Alma (Ellora Torchia), a ranger guide there to help him navigate the tricky terrain. When they get attacked by a group of marauders one night, who steal their gear (and shoes), they are left to hobble on their own, until they run into Zach (Reece Shearsmith), a kindly seeming man, who has crafted his own encampment. He takes them in, fortifies them with soup, new shoes, and, alas, deeply drugged drinks.

Turns out, he has actually gone insane, and believes by following a set program of bizarre rituals, he will be able to communicate with the forest gods and eradicate the virus himself. Escaping that insanity, the pair go from one bad scenario to an arguably worse one, finally tracking down Martin's former colleague (Hayley Squires) only to find more trouble with even deeper implications of insanity.

Wheatley's film feels rushed in places, and is violently incoherent in others, but its sense of immediacy is acute (he worked extensively with the production's various unions to ensure the cast and crew were properly protected). With its characters having plunged into bizarre cryptic conspiracy theories deep into the boreal heart of darkness, and the sense that reality has been splintered, it ends up being a pretty fair summation of our current life and times.

Unfortunately, along with its immediacy comes the somewhat slapped-together nature of its creation. Too much of the film feels rushed, and not entirely worked out (the script alone could have used another draft of two), and the psychotropic ending dazzles the eye but doesn't add much depth. It might not hold up under much scrutiny years from now, but it could hardly be more of the moment in the meantime.

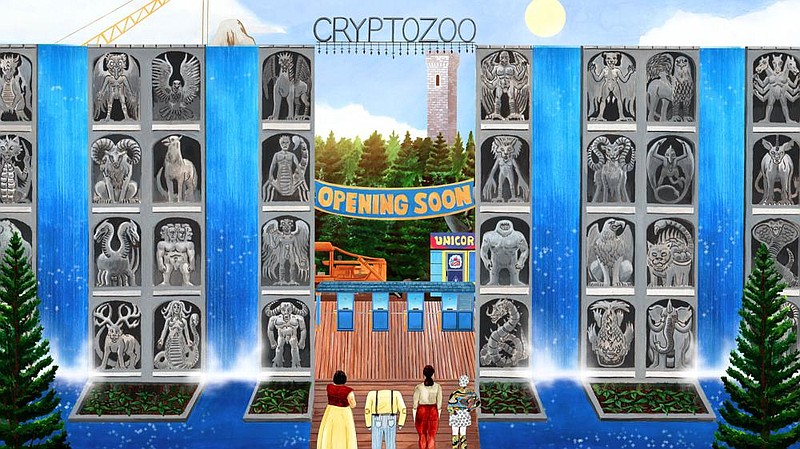

In direct contrast to that film's speedy creation, Dash Shaw's painstakingly hand-drawn animated feature, "Cryptozoo," was crafted over many long years. The result is a film whose halting animation style takes a bit of getting used to (instead of one smooth motion, the movements are broken up into several cells of action), but Shaw's screenplay is smartly taut, creating a narrative fantastic in subject matter and execution.

Set in the '60s, we meet Joan (voice of Grace Zabriske), a kindly woman who has spent her life trying to protect "cryptids" (mythical creatures such as unicorns, manticores, dragons and the like) from the world of men by creating a kind of zoo where they can all live under protected circumstances. Helping her acquire these creatures is Lauren (Lake Bell), whose childhood was saved from nightmares by a dream-eating Baku; trying to steal them for military uses is the film's villain, Nicholas (Thomas Jay Ryan), a capitalist swine with no sense of the divine magic the creatures possess.

Shaw, a graphic novelist by trade, has crafted a wondrous bounty of visual delights here, from the kaleidoscope-like color swirls and juxtapositions, to the rendering of the creatures themselves. He has also collected an impressive array of vocal talent to bring voice to his script, which works like something out of a Wes Anderson picture. It took years to bring it to the screen, but what he has produced is absolutely worth it.

Keeping with the trippy vibe, Rodney Ascher's "A Glitch in the Matrix," documents the rising belief that what we perceive as reality is in actuality a computer simulation. By this time, documentarian Ascher has carved out a sort of niche for himself: As with "Room 237" and "The Nightmare," he has gathered up fringe thinkers displaying a sort of group psychosis in order to explore other ways of seeing, and interpreting, our world.

His docs don't come down on either side of a given conundrum -- are any of the far-out, would-be explanations of "The Shining" in "Room 237" the least bit sensible? Is it possible for people experiencing the horror of sleep paralysis to share the same horrific vision in "The Nightmare"? -- but he carefully doesn't contradict any of his subjects either.

His new film, an exploration of what's known as "simulation theory," concerns a pattern of thought described back in 1977 by the widely adapted science fiction author Philip K. Dick during a public appearance in France, suggesting, "Matrix"-style, that all that we think we see and know is actually an intricate virtual reality, brought to us by an unseen technological force.

True to form, Ascher interviews numerous applicants to the theory -- many of whom portrayed by virtual reality avatars in their own homes -- including scholars, practitioners and skeptics, and bolstering their arguments with an assortment of other media, from Minecraft, Philip K. Dick-based films and crude computer animations, to video games, and youtube videos.

The views are intentionally conflictive -- one subject suggests the very idea of such conflict is the basis of the simulation -- and anything but conclusive, but, of course, that's the very point. It's disconcerting, but far less unsettling than "The Nightmare" -- one of the few true horror movies of the documentary genre I've ever seen -- save for the account of Joshua Cooke, who pled guilty to killing his parents in cold blood after cementing his belief that the ideas portrayed in "The Matrix" were completely real. Listening to his step-by-step description, from prison, of his descent into madness, and where those impulses took him, is to drop into first-person shooter psychosis.

Which creates a direct segue into "Mass," Fran Kranz' powerful drama set in the distant aftermath of a high-school shooting incident, in which 10 students lost their lives (a death toll that doesn't include the lone student shooter, who took his own life). The film opens with a shot of a church, but the title turns out to be a reverberating double entendre -- both the religious service toward forgiveness; and a term commonly used in conjunction with multiple-homicide shootings. The church, Episcopal it turns out, is the agreed-to meeting place for two sets of grieving parents: Gail (Martha Plimpton) and Jay (Jason Isaacs), whose teenage son Evan was killed some years before in a high-school massacre; and Linda (Ann Down) and Richard (Reed Birney), whose son, Haden, was the shooter, before killing himself in the school library.

They have agreed to meet, long after the lawsuits and legal wrangling have been settled, to possibly provide answers and solace to one another. As can be expected, the atmosphere is fraught with tension -- a setting Kranz, an actor making his directorial and writing debut, expertly mines before the couples arrive, with a kind but overenthusiastic church administrator Judy (Breeda Wool), fretting about the details of the food arrangement -- and the couples, wary, at first, of letting things get hostile, work diligently to avoid disagreement by staying mild (an arrangement of flowers Linda brings is speculated upon a great deal).

Eventually, however, the four wounded parents get down to more brass tacks, Gail and Jay eschewing their therapist's call for them to avoid "interrogation" questions, to get at the root of what they are after. In truth, as Kranz has the characters cannily come to understand, there are no details that shed new light, no explanations that help rectify what they've lost, only a grim understanding that, as parents, they are all subject to the laws of chaos and chance.

Unsurprisingly, Kranz has an actorly sense of conflict and explication, but, despite the limited setting (this could easily have been an adapted play), he gives his actors plenty of room with which to work, and the quartet are more than up to the task. They are each terrific, and given opportunity to shine, but it's Plimpton's monologue near the end about her son that becomes the film's singular tour-de-force moment, a scene with so many hooks and edges, it sticks to you like velcro.

Kranz is careful not to overstep his dramatic boundaries, difficult given the potentially melodramatic elements of the story, and allows his actors enough time to breathe so it avoids feeling polemic or preachy (an early scene with Gail and Jay in the car before they arrive is a scintillating bit of set-up, where words are spoken, but our attention, like that of the characters, is entirely elsewhere). No easy answers, thankfully, just brutal realizations that can't be avoided.