Benjamin Cordero, a high school student from western New York, has a thing for pop divas, but especially Lady Gaga.

Previously a casual fan of whatever was on the radio, Cordero was converted when the singer performed during the Super Bowl halftime show in 2017, and in the bountiful time since — which included "A Star Is Born" — his devotion has only grown.

This past year, as Lady Gaga prepared to release her latest album, "Chromatica," Cordero joined Twitter, the current hub of pop superfandom, where he dedicated his account to all things Gaga. He tweeted thousands of times during the pandemic, often in dense lingo and inside jokes, along with hundreds of his fellow travelers, known as Little Monsters — internet friends whom he calls his "mutuals."

But these days, in these circles, joy and community are rarely enough. There are also battles to be waged with rival groups or critics. And for Cordero, that meant trolling Ariana Grande fans.

SONGS LEAKED ONLINE

In October, with "Chromatica" having registered as a modest hit, Grande's own new album, "Positions," leaked online before its official release. Cordero, who liked Grande well enough but found her new music to be lacking, shared a link to the unreleased songs, much to the consternation of Grande fans, who worried that the bootlegged versions would damage the singer's commercial prospects.

Taking on the role of volunteer internet detectives, Grande fans proceeded to spend days playing Whac-a-Mole by flagging links to the unauthorized album as they proliferated across the internet. But Cordero, bored and sensing their agitation, decided to bait them even further by tweeting — falsely — that he had subsequently been fined $150,000 by Grande's label for his role in spreading the leak. "Is there any way I can get out of this," he wrote. "I'm so scared." He even shared a picture of himself crying.

"They were rejoicing," Cordero recalled giddily of the Grande fans he had fooled, who spread the word far and wide that the leaker — a Gaga lover, no less — was being punished. "Sorry but I feel no sympathy," one Grande supporter wrote on Reddit. "Charge him, put him in jail. you can't leak an album by the world's biggest pop star and expect no consequences."

2020 POP FANDOM

This was pop fandom in 2020: competitive, arcane, sales-obsessed, sometimes pointless, chaotic, adversarial, amusing and a little frightening — all happening almost entirely online. While music has long been entwined with internet communities and the rise of social networks, a growing faction of the most vocal and dedicated pop enthusiasts have embraced the term "stan" — taken from the 20-year-old Eminem song about a superfan turned homicidal stalker — and are redefining what it means to love an artist.

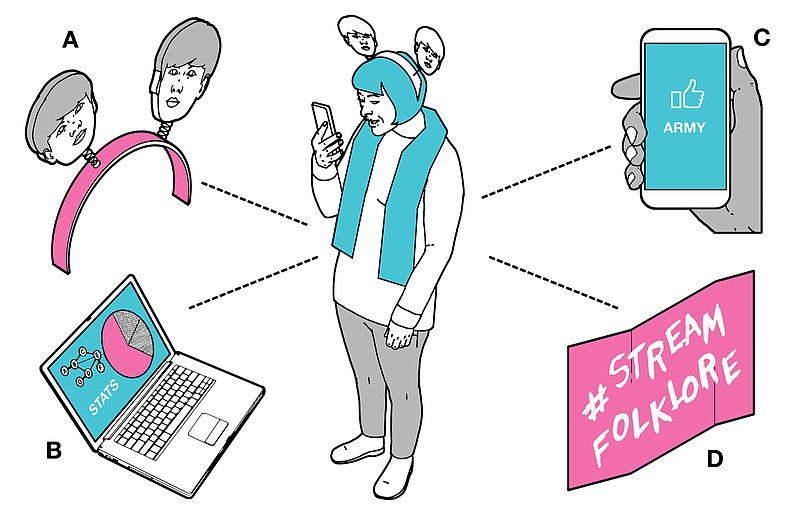

On what is known as Stan Twitter — and its offshoots on Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Tumblr and various message boards — these devotees compare No. 1s and streaming statistics like sports fans do batting averages, championship wins and shooting percentages. They pledge allegiance to their favorites like the most rabid political partisans or religious followers. They organize to win awards show polls, boost sales and raise money as grassroots activists. And they band together to pester — or harass and even dox — those who may dare to slight the stars with whom they have chosen to align themselves.

"These people don't even know who we are, but we spend countless days and months defending them from some stranger on the internet," said Cordero, who later revealed his Grande prank, gaining nothing but the ability to revel in the backlash.

"When someone says something about Lady Gaga that's negative, a little bit of yourself inside is hurt," he explained of his own loyalty. "You see yourself in your favorite artists; you associate with them, whether it's just the music or it's their personality. So when someone insults your favorite artist, you take that as a personal insult, and then you find yourself spending hours trying to convince someone in China that 'Born This Way' was her best album.

'A PLAYING FIELD TO US'

"It's definitely a playing field to us," Cordero added. "We throw them in the ring. They battle it out. We cheer them on."

This past year, one in which so much of everyday life was confined to virtual spaces because of the coronavirus, such antics garnered mainstream attention when fans of K-pop group BTS targeted President Donald Trump (and donated to Black Lives Matter) or when Taylor Swift supporters spit venom at those critics who thought her new album was anything less than perfect. Recently, NBC was forced to apologize after fans of Selena Gomez revolted in reaction to an off-color joke about the singer in a reboot of "Saved by the Bell."

But these battles also occurred at a near-constant clip on a smaller scale, in large part because of the incentives of the platforms where we now gather.

In the past, "the media that we had didn't facilitate these huge public spaces where attention is a commodity," said Nancy Baym, an author and researcher who has studied fan behavior online since the 1990s. "There's been this very long process of fans gaining cultural attention, gaining influence, and recognition of how to wield that influence; and now we're seeing it more because media are at a point where it's really putting it out there in front of us."

'THE COMMUNITY WITHIN'

Before destinations like Twitter, YouTube and Spotify — where numbers and what's trending are central to the interface — there were self-selecting mailing lists, bulletin boards, Usenet news groups, fan sites and official URLs where Grateful Dead or Prince fans could gather to digitize lyrics, sell tickets or trade tapes.

"It was more about the community within — connecting with other fans of the same artist — and wasn't as competitive," Baym said. "In some ways it was competitive, but it was more, 'How many times have you seen them live?'"

In the early 2000s, My–space in many ways marked a turning point, presaging an era of social media in which fans could connect directly with artists in a way they hadn't before, causing some people to become more hostile, abusive or entitled, Baym said. At the same time, "American Idol" pitted fandoms against one another in the form of a popular vote, and what were once more insular conversations among enthusiasts began oozing outward.

Paul Booth, a professor of media studies at DePaul University, researches how people use popular culture for emotional support and pleasure. He noted that in the last decade, "it's gone from a general understanding that there are people out there that call themselves fans, but we don't really know who they are or what they do, to, 'I'm a fan; you're a fan; everyone's a fan.' It's absolutely become everyday discussion.

'MEETING IN THE BASEMENT'

"Before, those people existed, but they were meeting in the basement yelling at each other," he added. "Now they're meeting on Twitter and yelling at each other, and everyone can see it."

"It all boils down to emotions, which is something we don't take seriously enough in our culture," Booth said. "When people are passionate about something to the point that they're identifying with it and it becomes part of who they are — whether it's a political party, a political person or celebrity — they're going to fight."

They're also going to buy. As artists have come to recognize their direct influence over swaths of their online public — sometimes siccing them on detractors or at least failing to call them off — they have also come to rely on their constant consumption, especially in the streaming era.

"You might have a local" — stan slang for a casual fan — "buy a record," said Cordero, the Lady Gaga loyalist. "But a person on Stan Twitter probably bought that record 10 times, streamed a song on three separate playlists and racked up hundreds and hundreds of plays."

'CHAINED AGAINST THE WALL'

He added, "It's basically promotion, free labor; we're practically chained against the wall with our phones." (Lady Gaga recently advertised "Chromatica"-branded cookies as an "Oreo Stan Club.")

In addition to fueling a merchandise boom, these pop fans have taken it upon themselves to learn the rules governing the Billboard charts and the streaming platforms that provide their data, hoping to maximize commercial impact for bragging rights.

But some see these relationships between fans and idols as parasocial ones, largely one-sided interactions with mass-media figures that masquerade as friendship, and worry about the long-term mental health effects of such devotion.

Haaniyah Angus, a writer and former teenage stan who has written about her experiences in the subculture, noted that standom was "very heavily dependent on capitalism and buying" in a way that convinced consumers, on behalf of "really rich people," that "their win is your win."

"For me and a lot of people I knew, a lot of it stemmed from us being very lonely, very depressed and anxious, being like, 'I'm going to forget what I'm going through at the moment, and I'm going to focus on this celebrity,'" she said.

This dynamic often served to stamp out dissent within the ranks, which was once seen as a crucial component of fandom.

"I don't think that toxic fandom is synonymous with stan culture," said Booth, the fan studies researcher. "But I think one of the dangers of stan culture — that is, the danger of a group of fans who are so passionate about something that they'll shut down negative comments — is that it can often shut down much-needed conversations where our media and celebrities let us down."