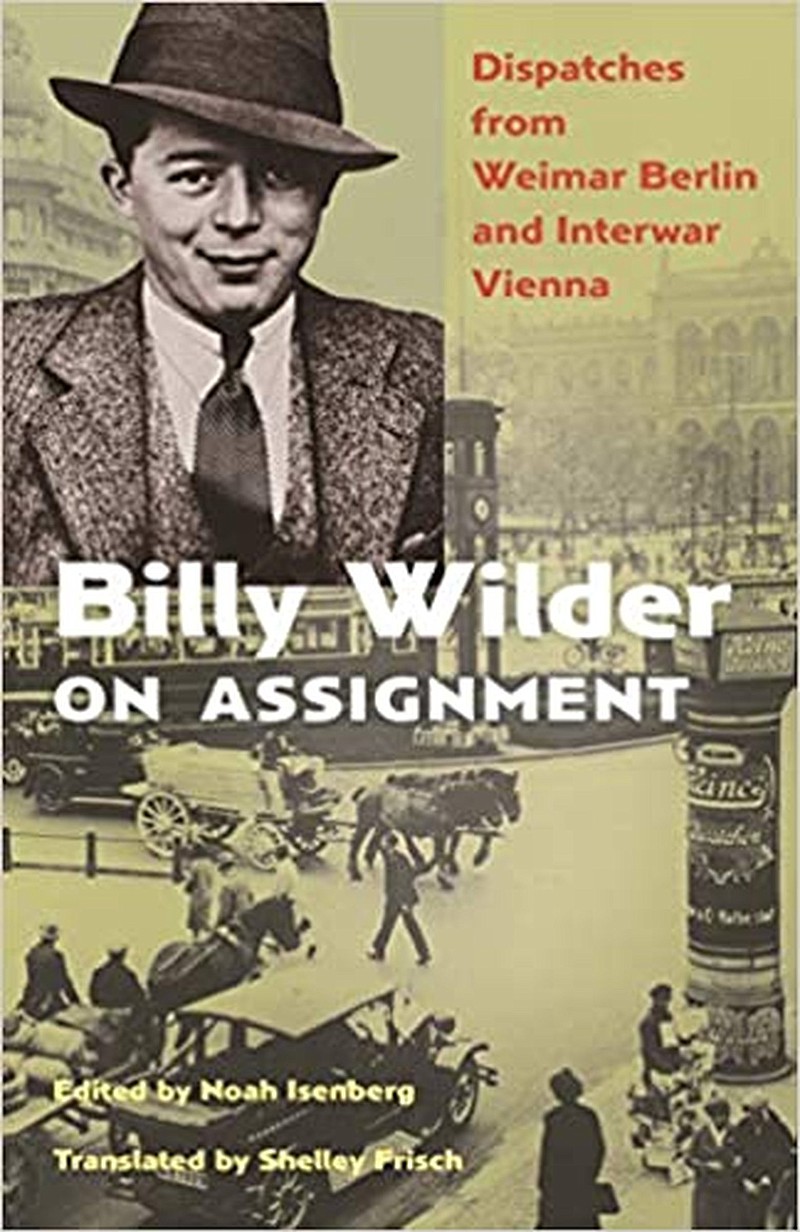

"Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna"

Edited by Noah Isenberg,

translated by Shelley Frisch

(Princeton University Press, $24.95)

During his long life, Billy Wilder earned seven Academy Awards for co-writing, directing and producing a series of clever, cynical, entertaining and occasionally insightful movies.

"The Lost Weekend" is one of the first credible and sympathetic depictions of alcohol abuse, and "Some Like It Hot" effortlessly incorporates "gender fluidity" into a gangland comedy. Wilder was doing that sort of thing in 1959, before the term had even entered the English language.

Later gender-bending comedies like "White Chicks" and "Sorority Boys" simply didn't have Wilder's fearlessness in tackling the subject. The latter movie, which hit the big screen in 2002, was so timid, lazy, empty and mirthless that it may have actually contributed to Wilder's death, at the age of 95, a few days after it opened.

Wilder won three of those Oscars for "The Apartment," which skewered sexual harassment decades before the #MeToo hashtag.

Despite having made movies that jolt and entertain viewers just as they did when they were made, the filmmaker seemed especially proud of having been featured as an answer in a New York Times crossword puzzle, "once 17 across and once 21 down." In 1925 Vienna, Wilder created those puzzles and still had a soft spot in his heart for newspapers.

The new anthology "Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna" proves Wilder's verbal and narrative gifts existed long before he set foot in Hollywood during the 1930s.

Wilder achieved most of his acclaim in America, yet it's astonishing how someone working in what would have been his third or fourth language was able to load up movies like "Double Indemnity" and "Sunset Boulevard" with hyper-verbal dialogue.

PUNCHY PUTDOWNS

The variety of pieces in "Billy Wilder on Assignment" demonstrates how effortlessly he could deliver putdowns. (When Peter Sellers had a heart attack during the shooting of Wilder's "Kiss Me, Stupid," the director famously quipped, "What do you mean heart attack?") He begins an interview with actor Adolphe Menjou ("Paths of Glory," "A Woman of Paris") by describing the flavor of a new-to-Germany beverage called, "Coca-Cola, which tastes like burned tires."

It's a gutsy way to begin the article, but Wilder -- who was in his early 20s at the time -- knew how to keep boilerplate celebrity profiles from getting dull or lifeless. (Oh, and three decades later, Wilder would have more fun at Coca-Cola's expense in his 1961 Cold War satire "One, Two, Three," which seems even funnier after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.)

Wilder's newspaper and magazine work ranged from short stories to man-on-the-street observations to film criticism, where he championed the work of Erich von Stroheim ("Greed"), whom he'd later direct in "Five Graves to Cairo" and "Sunset Boulevard"). "[Hollywood studios] hold onto Stroheim -- the way they would hold onto cactuses or decadent wind chimes," Wilder said of the older, less commercially successful filmmaker. "Out of respect for his unique skills people even buy into his moods."

Paul Schrader ("First Reformed") is one example of a critic whose own films demonstrate that he had plenty to teach the people who were already making them. With Wilder, it's a shame Berlin editors gave him such little space to weigh in on the films of the 1920s. Unlike Wilder himself, they might not have sensed the talent they were printing on a regular basis.

Despite their brevity, they do indicate where the future director would excel. His emphasis on pacing and appropriate casting shows up in the movies he made himself.

SEEDS OF JOURNALISM

For the themes in Wilder's movies, you can find the seeds in many of his more journalistic pieces. Some of his tales of Berlin nightlife might be a little too lively to be true. In the opening essay, about his two-month stint as a "professional dancer" who made himself available for young and old women needing a partner at a cafe, he tries to impress a partner by saying Kant was a Swiss national hero.

She lost interest in him quickly.

His chilling remarks about his experience as a type of gigolo would seem right at home in "The Apartment," "Irma La Douce" (about a prostitute) or "Some Like It Hot."

"I make my living honestly, honestly and with difficulty, because I dance honestly and conscientiously, " he writes. "No wishes, no desires, no thoughts, no opinions, no heart, no brain. All that maters here are my legs, which belong to this treadmill and on which they have to stomp, in rhythm, tirelessly, endlessly, one-two, one-two, one-two."

Thankfully, editor Noah Isenberg and translator Shelley Frisch help readers discover that Wilder, despite his mastery of ridicule, could be unabashedly sentimental or even gushingly enthusiastic. Air travel was relatively new in the late 1920s, and Wilder marveled how quickly it was becoming part of normal life. For a man known for wisecracks, Wilder could also demonstrate genuine awe. "Billy Wilder on Assignment" includes a sincere remembrance for Berlin critic Alfred Klaar as well as a heartbreaking followup to his report about working as a cafe dancer. One of his peers never got the chance to move on.

The new book makes one wonder what Wilder might have done with social media. His hot takes were always entertaining and occasionally pithy. His screenwriting career was taking off during the early 1930s, but Hitler's rise to power in 1933 convinced Wilder, who was a Jew, that he'd have to make his living in a safer environment. The German-speaking world's loss was America's gain.

As Isenberg notes in the introduction, much of the continued appeal of Wilder's work is that he was always an outsider. Wilder's columns about Vienna and Berlin may have been knowing, but he grew up in a town called Sucha in what's now Poland. Wherever he went, he was seeing the world with fresh eyes.

It is ludicrous to expect a 200-page collection to answer all the mysteries about what Wilder did as a middle-aged man. The movies he made here also featured the work of talented scribes like Charles Brackett, I.A.L. Diamond and Raymond Chandler. Nonetheless, it's a shame he didn't have a regular column or even a blog because newspaper work would always be his first love.

Maybe that's why his headstone reads: "I'M A WRITER BUT THEN NOBODY'S PERFECT."