The Supreme Court is leaving a pandemic-inspired nationwide ban on evictions in place, over the votes of four objecting conservative justices.

The court Tuesday rejected a plea by landlords to end the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention moratorium on evicting millions of tenants who aren't paying rent during the coronavirus pandemic. Last week, the Biden administration extended the moratorium by a month, until the end of July. It said then it did not expect another extension.

U.S. Judge Dabney Friedrich in Washington had struck down the moratorium as exceeding the CDC's authority, but put her ruling on hold. The high court voted 5-4 to keep the ban in place until the end of July.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rvLPorqY2tc]

In a brief opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh said he agreed with Friedrich's ruling but voted to leave the ban on evictions in place because it's due to end in a month and "because those few weeks will allow for additional and more orderly distribution of the congressionally appropriated rental assistance funds."

Also last week, the Treasury Department issued new guidance encouraging states and local governments to streamline distribution of the nearly $47 billion in available emergency rental assistance funding.

Chief Justice John Roberts and the court's three liberal members also voted to keep the moratorium in place.

Justices Samuel Alito, Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas said they would have ended it.

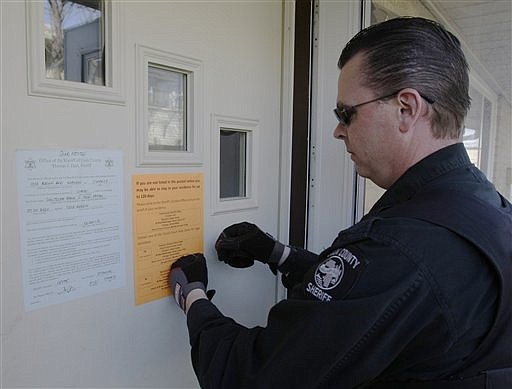

The eviction ban was initially put in place last year to provide protection for renters out of concern that having families lose their homes and move into shelters or share crowded conditions with relatives or friends during the pandemic would further spread the highly contagious virus.

By the end of March, 6.4 million American households were behind on their rent, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. As of June 7, roughly 3.2 million people in the U.S. said they faced eviction in the next two months, according to the U.S. Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey.

The court's ruling comes as new data shows that the gap between the most-vaccinated and least-vaccinated places in the U.S. has deepened in the past three months and continues to widen.

On a national level, the numbers appear good: About 300,000 new people are getting covid vaccinations every day in the U.S., and 54% of the full U.S population has at least one dose. The country's vaccine campaign is among the most successful in the world, allowing states to lift restrictions on business and socializing, as hospitalizations plunge.

But newly available county-level data show how those national figures hide very different local vaccination realities.

A Bloomberg analysis of almost 2,500 counties found that in the bottom fifth of counties, ranked by vaccination numbers, only 28% of people have received a first dose of a vaccine, on average, and 24% are fully vaccinated.

Bloomberg's analysis split counties into quintiles based on their latest one-dose vaccination numbers -- data came from the CDC and the state of Texas -- and then examined average vaccination rates over time. While previous analyses have examined county-level data on complete vaccinations, the newly available one-dose data gives a more up-to-date view.

[CORONAVIRUS: Click here for our complete coverage » arkansasonline.com/coronavirus]

In Arkansas, nearly half of the state's 75 counties are in the bottom quintile nationally, including six with fewer than 25% of people vaccinated with at least one dose. Just seven counties in the state have crossed the 40% threshold.

Gaps in vaccination rates can leave smoldering embers of infection, ready to set an epidemic newly ablaze elsewhere, and they can create fertile ground for new mutations, giving the virus a chance to evade vaccines, authorities sat.

"The consequences could be quite severe," said Timothy Callaghan, who studies rural health at Texas A&M University. "We're going to have counties where vaccination is rare and nowhere close to herd immunity, and others where it's high. We could be headed toward a divided country of haves and have nots."

At the start of February, the most-vaccinated fifth of counties had covered about 2 percentage points more of their residents than the least-vaccinated group of counties. By the end of March, that gap had grown to 12 percentage points. As of June 27, the gap is at a record level: The best-performing places have 32 percentage points more of their people vaccinated than the worst-performing group of counties.

The slowing rate of new vaccinations shows that despite the Biden administration's "month of action" to hit its vaccinations target of 70% of adults receiving at least one dose by July 4, some areas are proving hard to reach.

As of Monday, 66% of U.S. adults had at least one dose, and the current rate of shots means the administration will miss the July 4 goal. The less vaccinated parts of the country are one reason why, and contain millions of Americans who are eligible for shots but haven't received one yet.

Although surveys show widely varying reasons that people give for not getting covid-19 vaccinations, some demographic factors were strongly associated with vaccination decisions, according to Bloomberg's analysis. Among 20 factors, political partisanship was the strongest predictor of vaccination rates. Counties that voted most heavily for Republican Donald Trump had significantly lower vaccination rates.

Counties in states controlled by Republican governors and state legislatures also tended to have lower vaccination rates.

Political leanings don't necessarily explain why people opt out of vaccination. Often political affiliations are also associated with other factors that might influence that decision. Other top indicators included college education, income and home values, and population density.

Because those under the age of 12 aren't yet eligible to receive a vaccination, counties with relatively more children -- including in Texas, Kansas and Mississippi -- are also more likely to have lower vaccination rates as a result.

Meanwhile, after relentless months of social distancing, online schooling and other restrictions, many kids are feeling the pandemic's toll or facing new challenges navigating reentry.

A surge in teen suicide attempts and other mental health crises prompted Children's Hospital Colorado to declare a state of emergency in late May, when emergency department and hospital inpatient beds were overrun with suicidal kids and those struggling with other psychiatric problems.

Typical emergency-department waiting times for psychiatric treatment doubled in May to about 20 hours, said Jason Williams, a pediatric psychologist at the hospital in Aurora.

Williams said issues the hospital is treating are "across the board," from children with previous mental health issues that have worsened to those who never struggled before the pandemic.

Like many states, Colorado doesn't have enough child and teen mental health therapists to meet demand, an issue even before the pandemic, Williams said.

Children who need outpatient treatment are finding it takes six to nine months to get an appointment. And many therapists don't accept health insurance, leaving struggling families with few options. Delays in treatment can lead to crises that land kids in the ER.

Those who improve after inpatient psychiatric care but aren't well enough to go home are being sent out of state because there aren't enough facilities in Colorado, Williams said.

Other children's hospitals are facing similar challenges.

At Wolfson Children' Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla., behavioral unit admissions for kids in crisis ages 13 and younger have been soaring since 2020 and are on pace to reach 230 this year, more than four times higher than in 2019, said hospital psychologist Terrie Andrews.

For older teens, admissions were up to five times higher than usual last year and remained elevated as of last month.

Zach Sampson, 16, says "just a lot of stuff" triggered his first crisis last August. The Jacksonville, Fla., teen struggled with online education and spent hours in his room alone playing video games and scrolling the internet.

He revealed his suicidal thoughts to a friend, who called the police. He spent a week in the hospital under psychiatric care.

Both of his parents have worked in mental health jobs but had no idea how he was struggling.

The teen started virtual psychotherapy, but in March his self-destructive thoughts resurfaced. Hospital psychiatric beds were full, so he waited a week in a holding area to receive treatment, his mother, Jennifer Sampson, recalled.

Now on mood stabilizers, he's continuing therapist visits, has finished his sophomore year and is looking forward to returning to in-person school this fall. Still, he says it's hard motivating himself to leave the house to go to the gym or hang out with friends.

"When the pandemic first hit, we saw a rise in severe cases in crisis evaluation," as kids struggled with "their whole world shutting down," said Christine Certain, a mental health counselor who works with Orlando Health's Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children. "Now, as we see the world opening back up, ... it's asking these kids to make a huge shift again."

Information for this article was contributed by Andre Tartar, Kristen V Brown and Tom Randall of Bloomberg News (TNS); and by Lindsey Tanner and staff members of The Associated Press.