Ten years have passed since a team of Navy SEALs and Army helicopter pilots flew 162 harrowing miles into Pakistan to kill Osama bin Laden, a mission that represented perhaps the U.S. military's only pure victory in 20 years of the war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

This week, the two men at the center of ordering and overseeing the raid -- former President Barack Obama and Ret. Adm. William McRaven -- met at Obama's Washington, D.C., office to reflect on the operation ahead of its 10th anniversary, which is Sunday.

For both men, the meeting was an opportunity to recognize those who made the mission successful. "The number of people who operated at the very highest levels for a sustained period of time; that's something I appreciate even more a decade later," Obama said.

And it was a moment for both to take stock of a long war and a divided country. For McRaven, who planned and then commanded the mission, the most emotional moment 10 years on had nothing to do with the raid, but came with a memory of its aftermath, when McRaven and Obama flew to Fort Campbell, Ky.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yVZaUtnvJKs]

After meeting privately with the SEALs and the Night Stalker helicopter pilots who executed the raid, Obama spoke to an airplane hangar full of troops from the 101st Airborne Division.

Bin Laden was dead. But the 101st was still cycling troops through Afghanistan and losing soldiers to a conflict of ill-defined goals that would grind on for another decade.

"Well, you came off the platform. You went down ...," McRaven recalled to Obama in the video. McRaven pursed his lips, broke eye contact with Obama and fought to contain his emotion.

"That's how I felt," Obama said, shaking his head.

"And, of course, the soldiers start lining up, and you start shaking hands," McRaven continued.

The moment, taped Monday by the Obama Foundation, captured the bittersweet nature of one of the most consequential missions in U.S. military history. For McRaven, it was as if the triumph at the compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, couldn't be separated from two decades of war that, in Obama's words, had produced outcomes everyone knew to be "ambiguous at best."

The past few weeks have included a series of milestones in the long wars that fall under the broad umbrella of what began as America's Global War on Terror. Last month, President Joe Biden promised to pull the last American forces out of Afghanistan by Sept. 11, the 20th anniversary of the attacks that bin Laden inspired, funded and helped organize.

"American leadership means ending the forever war in Afghanistan," Biden reiterated to applause from a joint session of Congress on Wednesday night. In ticking off the accomplishments of that 20-year war, there wasn't much for him to tout beyond the degradation of al-Qaida and the death of bin Laden.

The Obama-McRaven conversation took place in front of a framed American flag signed on its hidden, reverse side by all the service members who took part in the bin Laden raid. The flag captures the unusually personal nature of the mission for Obama.

When he was inaugurated as president in 2009, the hunt for bin Laden had largely grown cold. Obama immediately instructed his CIA director, Leon Panetta, to make killing or capturing bin Laden a top priority. "I want to see a formal plan for how we're going to find him. I want a report on my desk every thirty days describing our progress," Obama recalled in his memoir.

Once the CIA's painstaking work uncovered bin Laden's possible hide-out, Obama and McRaven immersed themselves in the mission.

Part of the commander-in-chief's job is to authorize military actions. But it's exceedingly rare that a president is briefed on the details of how a raid will be conducted or gives the order to launch it.

"These issues of war are treated as abstractions," Obama said to McRaven. "We forget that these are folks who have families and loved ones and that they are carrying a burden on behalf of hundreds of millions of Americans."

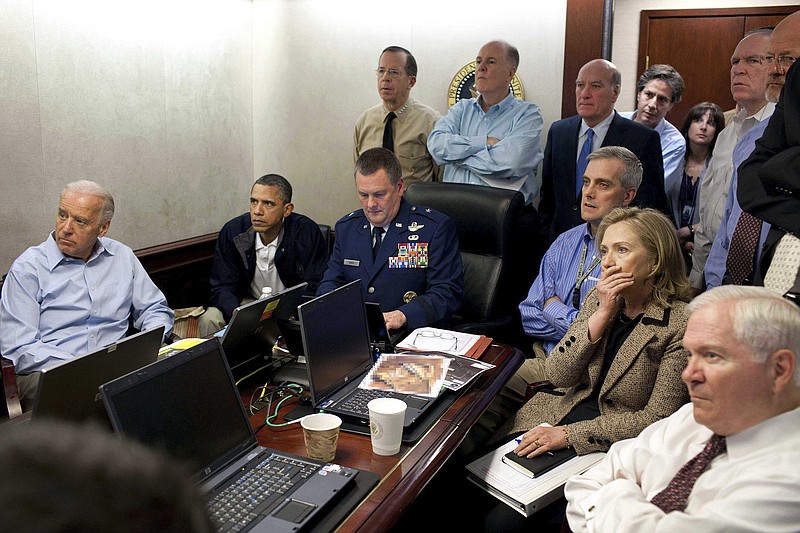

The bin Laden raid was also the only time in Obama's presidency that he watched a military operation unfold on live video.

The mission was personal for Obama in another way. His prospects for a second term were potentially riding on it. Obama's national security Cabinet was split on whether to take the risk of sending the SEALs into Pakistan when it wasn't certain that bin Laden was at the compound.

Panetta, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Joint Chiefs Chairman Adm. Mike Mullen were all in favor of the raid. Biden and Defense Secretary Robert Gates were opposed.

Gates noted that former President Jimmy Carter had never recovered politically from a botched mission in 1980 to rescue the U.S. hostages in Iran. "The unspoken suggestion was that I might not either," Obama wrote in his biography "A Promised Land."

In the days after the raid, Obama recalled meeting with a 14-year-old girl who had lost her father in the World Trade Center attack when she was 4.

She "had actually talked to her father in the building," Obama recalled to McRaven. "It was the last conversation she remembered with her father. ... It brought home the fact that so many of the issues we deal with are big historic issues, but they are also issues that are very personal for people."

The 10th anniversary of the bin Laden raid is also a reminder of how much the threats to the United States have changed in the course of a decade. In hindsight, the mission marked a time when Republicans and Democrats were united in believing that the preeminent threat to American security was external, not internal.

Today, U.S. officials routinely describe white supremacist or ultranationalist ideologies as posing a threat as great as -- if not greater than -- al-Qaida and its progeny. In recent testimony, FBI Director Christopher Wray said the bureau had "elevated racially and ethnically motivated violent extremism to our highest threat priority, on the same level with ISIS and homegrown violent extremists."

On Wednesday as he spoke to Congress, Biden seemed to agree, describing the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol and efforts to reverse the outcome of the 2020 election as "the worst attack on our democracy since the Civil War."

The threats of domestic extremism and Islamist militancy can seem mutually reinforcing. Far-right groups have fed off currents of xenophobia and hostility to Islam that bin Laden sought to foment with the 9/11 attacks.

And in one instance they succeeded where al-Qaida failed. The 9/11 plot that bin Laden orchestrated envisioned a plane plowing into the Capitol, but it plunged into a Pennsylvania field after passengers stormed the cockpit.

On Jan. 6, domestic extremist groups and radicalized supporters of President Donald Trump breached the defenses of the U.S. Capitol. U.S. officials have said many of those involved in the attack followed paths of indoctrination and radicalization not dissimilar to adherents of Islamist militancy.

Perhaps this aftermath explains Obama's mixed feelings about his administration's greatest military and intelligence triumph. He wrote in his recent memoir that he was inspired by the "unity of effort" and "sense of common purpose" that U.S. government officials brought to the bin Laden mission, but wondered why it was "possible only when the goal involved killing a terrorist?"

To Obama, his question was a measure of how far his presidency "still fell short" of what he wanted to be. It was, he wrote in closing, a sign of "how much work I had left to do."