Lisa Evans remembers a man in Little Rock who did not want to be around his family members because he was afraid they might hurt him.

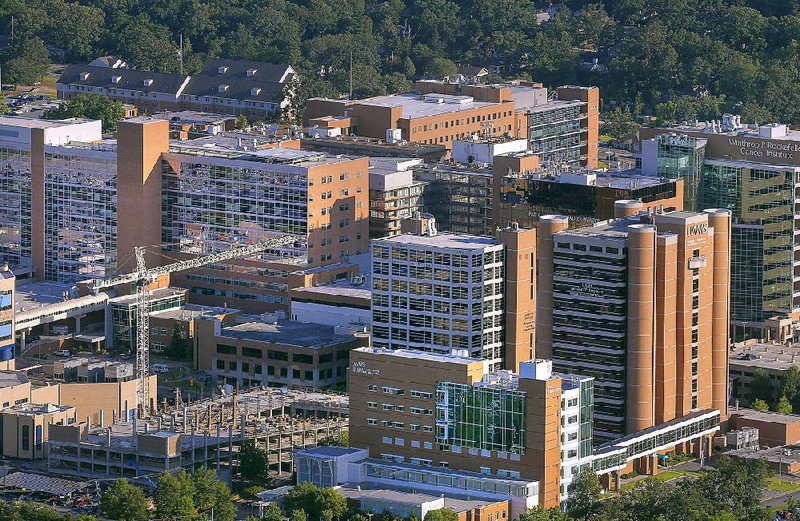

With the help of Little Rock police, the Crisis Stabilization Unit at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, where Evans is the director, was able to get the man, who was struggling with psychosis and paranoid thoughts, the mental health care he needed and to reunite him with his family in a matter of days.

"We feel most successful when we get someone like that, [when] we get them stabilized and get them into a housing environment," she said.

Almost two years ago, the Little Rock Community Mental Health Center would have been a potential resource to help the man. Since the center closed in September 2019 after more than 50 years of operation, other organizations in Pulaski County have made concerted efforts to reach out and to help the population that relied on its services.

The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported at the time that the Community Mental Health Center staff worked to notify about 2,500 clients that the center would close. Officials attributed the closure to financial deterioration.

Advocates for the population the center served -- people with low incomes, mental disorders, housing insecurity or a combination of all three -- said at the time that they were concerned about a gap in the treatment landscape without the long-standing center.

Before July 1, 2019, the center held the contract to be the designated community mental-health center providing indigent care in the southern region of Pulaski County. Centers for Youth and Families has held that contract ever since.

Centers for Youth and Families spokesman Bill Paschall said the organization is "confident" it reached 90% or more of the Little Rock Community Mental Health Center's former clients. The organization used social media, flyers, mail and phone calls to try to connect with as many people as possible, he said.

Centers for Youth and Families addresses this population's mental health needs while Pulaski County's Community Services department addresses their housing needs, said Fredrick Love, the county's director of community services.

Love, who is also a Democratic member of the Arkansas House of Representatives, said he believes the county inherited 250 to 275 clients from the Community Mental Health Center.

On April 30, Pulaski County received $2.9 million from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's Continuum of Care grant program, which focuses on rehousing people who are homeless and providing them with the resources to remain housed.

More than $2.5 million of the allocated funds are for county programs designated as Little Rock Community Mental Health Center offshoots, according to the award letter from the housing department.

"This is a vulnerable population, so we try to go the extra step to ensure that we keep them housed," Love said. "We're calling all our clients monthly to check in on them, but [our goal is] also to be a liaison for our client to their mental health provider."

A $40,000 grant from the federal housing department in 2019 covered a year's salary for a new case manager at Centers for Youth and Families. Paschall said the case manager still works for the organization, helping unhoused people access mental and physical health care and develop job and life skills, as well as giving them "a lot of support with day-to-day life stuff."

"The goal is to prepare them to be self-sufficient when they leave the program and give them the tools to hopefully succeed," Paschall said.

'A NEW CULTURE'

Advocates say community outreach is the future of aid for people who struggle with mental illness and homelessness.

"Brick and mortar is a thing of the past," said Mandy Davis, the director of Jericho Way Day Resource Center, a homeless aid organization. "It's a dinosaur, and we need to be on the streets. [In] communities that do well, that's where they start, creating a new culture around mental health treatment."

The biggest challenges to meeting people's needs are transportation and geography, said Aaron Reddin, founder of The Van, a Little Rock-based nonprofit that takes food and other supplies to people who live outside. Some people do not have cars or the money for public transportation, so services to help them should be "strategically placed" around the Little Rock metropolitan area, he said.

The Van provides clothing, blankets, tents, hygiene products and other physical resources to people living on the streets. Reddin said the nonprofit also aims to build relationships and trust with the people it helps.

"If we can connect them with service providers, that's better, but we want to do what we can for people where they are," Reddin said.

Evans agreed with Davis and Reddin that direct mobile aid is the best way to help people, especially since coordinated aid programs are "expensive and intensive." In an ideal program, a physician, a nurse and a case manager would assess a person's mental and physical health, any potential medications that could help the person, and options for housing assistance and "locational rehabilitation," Evans said.

Police can help if they are trained in community outreach instead of raising their weapons and arresting a person living on the street, Evans and Davis both said.

The Little Rock Police Department hopes to hire a social worker, and Davis said this is a positive step. However, more trained mental health professionals on the streets will do the most good, especially for people dealing with substance use disorder, she said.

"The majority of times, police and paramedics do the right thing, but when they don't, and someone is experiencing psychosis, we can't help without them," Davis said. "We need the community to come together. We all need to be speaking the same language with regards to people who are suffering in our city."

Jericho Way has seen an increase in calls and requests for help with homelessness, mental illness and substance use since the covid-19 pandemic took root in March 2020, Davis said.

The organization works closely with the Crisis Stabilization Unit, which in turn works primarily with homeless shelters to get people housed as quickly as possible, since shelters are the most immediate housing options in Little Rock, Evans said.

The easiest cases are the ones in which a person in need has at least one advocate, sometimes from Jericho Way, and helping people is more challenging if they do not have an ID or a social security number, Evans said.

The consensus among advocates is that any treatment gap left by the closure of the Little Rock Community Mental Health Center is difficult to quantify, but a variety of groups have since done their best to meet people's needs.

"It's been a wild last few years, regardless of that change," Reddin said.