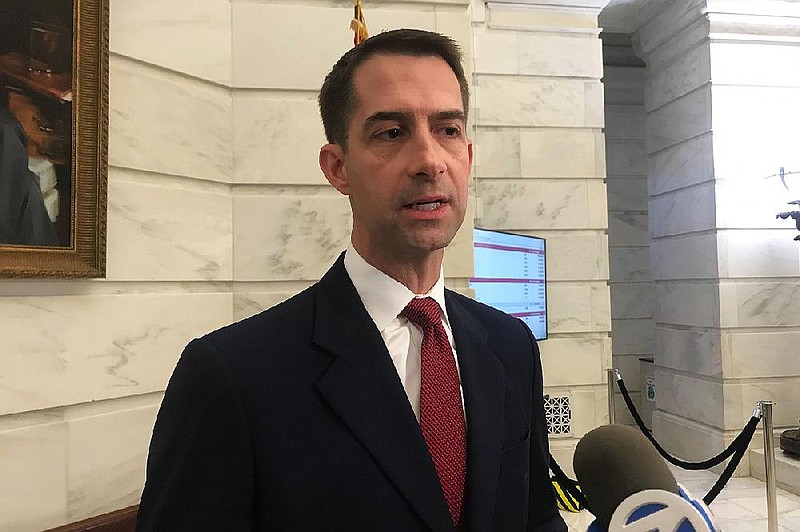

WASHINGTON -- Fifteen months after accusing U.S. Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., of spreading a "debunked" covid-19 conspiracy theory, The Washington Post on Friday added a correction to its story acknowledging that it can't back up some of the story's claims -- and never could.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kf12P5nIZug]

The Feb. 17, 2020, article accusing Cotton of conspiracy-mongering now bears this correction: "Earlier versions of this story and its headline inaccurately characterized comments by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) regarding the origins of the coronavirus. The term 'debunked' and The Post's use of 'conspiracy theory' have been removed because, then as now, there was no determination about the origins of the virus."

A molecular biologist who is quoted in the article told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in emails Friday that the story by national and breaking-news reporter Paulina Firozi omitted his statements supporting the leaked-lab hypothesis that Cotton cites.

"The experience -- being quoted in the February 17 Washington Post article in a manner that materially misrepresented my views -- was eye-opening," said Richard Ebright, a Rutgers University chemistry and chemical biology professor. "Watching 'the first rough draft of history' being written as a partisan exercise, rather than a journalistic exercise, was dismaying."

With President Joe Biden last week calling for an intelligence community assessment of the evidence, news organizations are revisiting questions about the virus's origins, reconsidering theories some had once dismissed out of hand.

Cotton early on urged officials to pursue the lab-leak theory, arguing that covid-19's emergence -- so close to the Wuhan Institute of Virology -- made it plausible.

Ebright, whose objections were previously noted by journalist Michael Tracey, said the lab-leak hypothesis has long been the most plausible explanation for the outbreak of covid-19 in downtown Wuhan.

Recent reevaluations aren't the result of any new scientific discoveries, Ebright told the Democrat-Gazette.

"All evidence available today was available twelve months ago, and most evidence available today was available fifteen months ago," he wrote. "All that has changed is that the small circle of scientists and larger number of journalists that seized control of the narrative in February 2020 and falsely claimed for fifteen months that a natural-spillover origin of COVID-19 was an established fact now have lost control of the narrative."

In the Post's updated headline, Cotton's theory has been recategorized from "conspiracy" to "fringe."

Post Vice President for Communications Shani George said the correction was posted Friday, writing in an email, "We do not have anything to add beyond the correction appended to the story."

From the beginning, Cotton has denounced China's lack of transparency about covid-19's origins, emphasizing its emergence just miles from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which studies and experiments with coronaviruses.

While arguing that covid-19's emergence was "most likely" natural in origin, Cotton wrote in a Feb. 16, 2020, tweet that an accidental lab release, resulting from legitimate but sloppy research, was the second-most-likely explanation. The lawmaker from Little Rock dubbed the scenario "Good science, bad safety (eg, they were researching things like diagnostic testing and vaccines, but an accidental breach occurred)."

It was less likely, Cotton wrote, that covid-19 was an "engineered bioweapon" that was inadvertently released in China's own backyard. A "deliberate release," Cotton said, would be "very unlikely."

Cotton wrote the series of tweets after an online version of Firozi's story appeared, Ebright noted.

And in a Fox News interview that preceded it, Cotton seemed open to the idea that covid-19 might be related to biological warfare, Ebright said.

"This was irresponsible," he said.

Cotton's response to journalist Maria Bartiromo is open to interpretation, however.

"I went back and looked at Cotton's [interview] on Fox that thrust him into the forefront and he was pretty nuanced," wrote journalism ethics expert Al Tompkins, a senior faculty member at the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Fla.

"Maria, it seemed, was pushing him to go further out on the bioweapons claim but he didn't go there," Tompkins said in an email to the Democrat-Gazette.

Cotton's view, initially discounted by The New York Times, the Post and others, is no longer dismissed out of hand.

With the initial outbreak linked to a city with a major virus-testing laboratory, given what was known, Cotton "was making an argument with plausible supporting evidence," journalist David Leonhardt acknowledged in the Times' Thursday "Morning Newsletter."

Previous dismissal of the lab-link theory "appears to be a classic example of groupthink, exacerbated by partisan polarization," he wrote.

The Times is sticking by its Feb. 18, 2020, article headlined "Senator Tom Cotton Repeats Fringe Theory of Coronavirus Origins."

Hong Kong business correspondent Alexandra Stevenson, who wrote the story dismissing Cotton's questions and echoing Beijing's official line, referred questions about her story to the Times' corporate communications office. The office didn't immediately respond to an email seeking comment.

Her article is still posted on the Times' website in English and Chinese; no correction or clarification is attached.

Cotton was one of the first lawmakers to sound the alarm about the coronavirus.

On Jan. 30, 2020, he told fellow members of the Senate Armed Services Committee that the virus was "the biggest and the most important story in the world."

"This coronavirus is a catastrophe on the scale of Chernobyl for China. But actually, it's probably worse than Chernobyl, which was localized in its effect. The coronavirus could result in a global pandemic," he warned military officials and colleagues. Chernobyl was a 1986 nuclear plant disaster in Ukraine.

"I would note that Wuhan has China's only biosafety level-four super laboratory that works with the world's most deadly pathogens to include, yes, coronavirus," Cotton added.

In a Tuesday analysis titled "How the Wuhan lab-leak theory suddenly became credible," Washington Post fact checker Glenn Kessler acknowledged that Cotton had been ahead of the curve.

"Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) from the start pointed to the lab's location in Wuhan, pressing China for answers, so the history books will reward him if he turns out to be right," Kessler wrote.

In an interview with the Democrat-Gazette, Cotton said political biases prevent much of the mainstream media from seeing and stating the obvious.

"If you go back to last January and February, when I first rang the alarm on this, all I said was, 'Just look at what your own two eyes suggest. Follow basic common sense.' This virus didn't emerge in some rural village next to a mountain cave full of bats. It emerged in a city larger than New York a few blocks down the road from labs where they just happened to research dangerous coronaviruses," Cotton said.

"Democrats and most of the mainstream media condemned me at the time as a hysterical conspiracy theorist. When President [Donald] Trump said the same thing, certainly they condemned him. They said this had been widely debunked," Cotton said.

The lab-leak hypothesis, never fringe, was never debunked, Cotton said.

"The question is why did the media reject this theory that is obviously plausible and reasonable and should have been investigated carefully and thoroughly by the media from the very beginning? It's because I was the one saying it. It's because it might somehow help Donald Trump's reelection campaign. Now that he's no longer in office, the media's taking a second look at it," Cotton said.

Tompkins, the Poynter Institute journalism ethics expert, said Cotton's covid-19 hypothesis was aired during a period when "misinformation" was abundant.

"[A]ll of this unfolded at a time when Trump and his circle were associated with all sorts of crazy conspiracy stuff and this got lumped in with it as just another thing he was peddling," he said in an email.

"Maybe that is one of the costs of misinformation in a time of pandemic.

"But Cotton can rightfully claim his comments were summarily dismissed when they turn out to be valid, even a year later," Tompkins said.

"One of the things this pandemic teaches us is that we cannot be too confident about what we think we know. We have to remind the public that the information we have is just a snapshot in time [that] might change," he wrote.

"We saw it with evidence of how the virus spreads, whether masks are useful or not, whether the virus spreads outdoors with the ease once thought and so on," he wrote.

"We are changing engines on the plane mid-flight. So the reporting has to constantly remind people of the uncertainty and that we are reporting the evidence as it stands," Tompkins added.