Health officials are working to secure funding to increase covid-19 tracking through wastewater in Arkansas.

Tracking the virus and other diseases through wastewater can provide an early warning system, according to Richard McMullen, senior scientist for the Arkansas Department of Health.

Several scientists have done research projects using wastewater to track covid-19 in the state during the course of the pandemic, and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently partnered with the Department of Health to open two testing sites in Arkansas.

Now McMullen; David Ussery, a genomics professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock; and Wen Zhang, a civil engineering professor at the University of Arkansas are preparing to apply for a $30 million grant from the CDC's U.S. Public Health Pathogens Genomics Centers of Excellence that could expand general surveillance, research and training for covid and other diseases.

McMullen said if they receive the grant, he hopes to use some of the funds to bring more wastewater treatment facilities online. Ussery and Zhang also want to expand genetic testing to track covid variants in the state.

HOW IT WORKS

Most people think of covid-19 as a respiratory disease that is passed through small droplets from something like a sneeze, but Zhang said infected people also pass the virus in their intestines through feces, which end up in the wastewater system.

By testing wastewater, scientists can get a general idea of how much virus is in the population served by the treatment plant, she said.

Wastewater treatment plant officials collect composite samples as part of their daily procedures so collecting an extra sample isn't much more work, Zhang said.

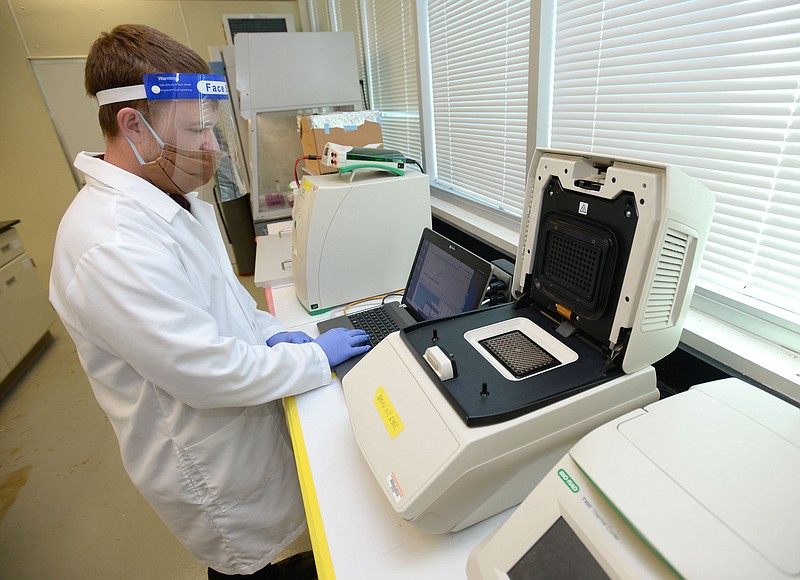

Zhang's lab at the University of Arkansas uses quantitative polymerase chain reaction, or QPCR tests, similar to the PCR tests used to screen for the virus in nasal swabs, to measure the relative concentration of covid virus genes in each milliliter of wastewater. It's hard to directly translate the results to a specific number of individuals in the population who are infected because people shed different amounts of virus depending on how sick they are, and on different days of their infection, she said.

However, by monitoring the relative concentration of virus in wastewater over time, scientists can tell if covid cases are increasing or decreasing in the community, Zhang said.

Genomics sequencing can also be used to track variants of concern through wastewater, Ussery said. UAMS has new technology that allows genetic sequencing tests that can be done rapidly for for about $10 each, he said. The technology can also be used to sequence other types of virus and bacteria, he said.

Wastewater testing has lots of advantages, according to McMullen. For example, for the cost of one sample at a wastewater treatment facility, scientists can know what's happening in an entire community, he said. It's also very timely, because people start shedding virus in fecal matter days ahead of when they begin feeling bad, he said.

Another advantage of wastewater testing is that it's anonymous and noninvasive because it doesn't single out anybody, Ussery said.

However, the method has limitations because researchers can't pinpoint exactly where in a wastewater system the virus came from, McMullen said.

"It will never replace hospital reporting, but it will supplement it," he said.

LOCAL RESEARCH

The CDC began tracking covid-19 through wastewater in September 2020 through a grassroots effort of academic researchers, according to a news release. The effort became a national surveillance system that encompasses 37 states and 400 testing sites, it states.

In February, the CDC announced the wastewater data is available on the agency's online covid tracker.

The Arkansas Department of Health partnered with the CDC to establish testing sites in Blytheville and Redfield about three months ago, McMullen said.

Zhang was awarded $40,000 through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act in July 2020 to study wastewater, according to a news release from the University of Arkansas.

At the time, covid-19 tests for individuals were in short supply, so wastewater testing offered another way to monitor the virus as it spread, she said.

Between July and December 2020, Zhang's team took samples from 14 sites in Northwest and Central Arkansas, including in Fayetteville, Springdale, Rogers, Fort Smith, West Fork, Prairie Grove, Little Rock, Pine Bluff, Conway and at a Washington County lift station, she said.

The samples showed increases in the virus three to five days before the number of cases reported in the community increased, Zhang said.

Zhang's team also tested wastewater at various stages in the wastewater treatment process to see if the treatment removed the virus or if it was being passed on to rivers and lakes. The good news is that little to no virus was detected in effluent -- treated wastewater flowing out of the plants, she said.

Ussery's team monitored wastewater in Conway weekly for about six months last year, he said. The team found it could detect the levels of covid going up and down, following the number of cases in the community, he said.

PUBLIC HEALTH TOOL

Wastewater monitoring can help hospitals and public health officials prepare for a surge, McMullen said.

Biobot, a company based in Cambridge, Mass., works with local, state and federal governments to track covid-19 through wastewater testing across the U.S., according to spokesman Jennings Heussner. The company was established in 2017 as part of doctoral research at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology to use wastewater to track opioid use, he said. In 2020, it shifted to a focus on tracking covid-19.

The company's clients have used information gathered from wastewater tracking to make a range of public health decisions, Heussner said. For example, Cambridge used the data as one of three metrics to determine when public schools should switch to remote learning, he said. The Boston Children's Hospital also used the information the company gathered to make decisions about when elective surgeries should be postponed or resumed, he said.

In Newcastle County, Del., health officials used wastewater tracking from manholes at the neighborhood level to determine where to position mobile testing and vaccination units, Heussner said.

Wastewater testing can be applied to any virus or bacteria that might be shed in fecal matter, McMullen said. In the future, the technology could be used to monitor food-borne illness outbreaks, antibiotic resistant bacteria, hepatitis A and other diseases.

"I truly believe this is the future of surveillance or at least supplementing surveillance for communities," McMullen said.