Little Rock's police chief and other members of a panel fielded questions and some sharp criticism from community members Saturday morning in the town hall-style Courageous Conversations meeting at a church in southwest Little Rock.

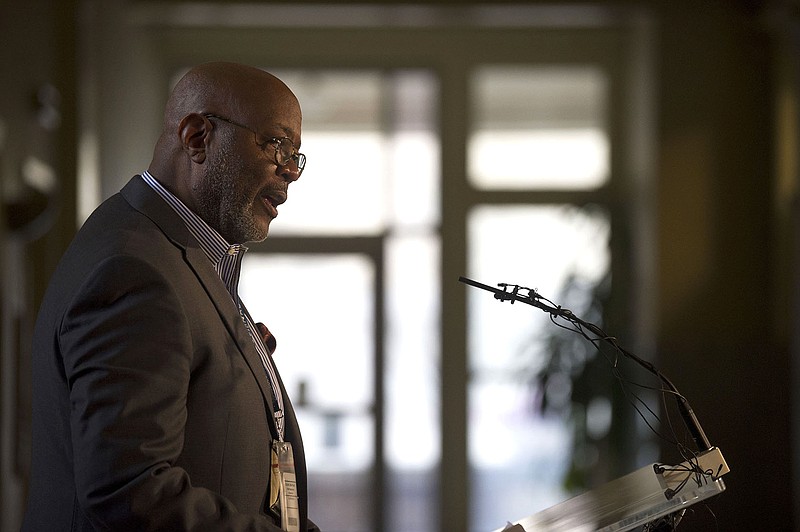

Chief Keith Humphrey was joined on stage at the Otter Creek Community Church by Terrell Stokes, a deacon at the church; police Lt. Kendel Cole; and Doris Gonzalez, a banker who used to work with the city as a community resource specialist. Police communications manager Laura Martin moderated.

The group had only just introduced themselves when a man who identified himself as Byron Norwood took the microphone and asked what the point of the meeting was. He said he had heard nothing new in more than 50 years of attending community meetings with police in the city.

"Nothing that any one of you have said this morning is courageous," Norwood said.

Norwood criticized the idea that the increase in crime Little Rock is experiencing is part of a national trend, something that Humphrey and Mayor Frank Scott have expressed countless times in recent months.

Norwood thinks that explanation is a crutch because it lets city officials shift responsibility for fixing the violence problem to other groups, like the federal government.

Humphrey said he thinks putting Little Rock's crime problem in context with what's going on in the nation is important, he told Norwood, and the numbers show that crime in the city is up as well as in the country as a whole.

Those statistics, Norwood countered, don't mean much to the families of people hurt and killed in the city by criminals.

"I have little confidence in people who repeat the same rhetoric" without generating results through action, Norwood said.

Humphrey told Norwood he thought his statements were "very unfair" to his department's officers and to the town hall participants.

"I think before you start talking like you're talking, you need to figure out what's going on in the city," Humphrey said.

Stokes said he was disappointed that Norwood seemed angry with what the panelists had to say before they had even opened their mouths.

"To tell us we're not doing anything is a bit much," Stokes said.

But, Norwood insisted, the city's officials have a responsibility to do more about crime, including addressing root causes like poverty and bleak outlooks for teenagers.

"You don't treat a symptom, you address a problem," Norwood said. "And I suggest the problem is hopelessness."

Norwood told the panelists about his own work trying to better young people in his community by lending them a hand when they show initiative and entrepreneurial spirit. He suggested that these kind of individual and community-based actions would have more impact on the problem than police, who he thinks should be a last resort.

Humphrey and Scott, who arrived at the town hall a little after the first question, agreed that more than anything, the city needs people to buy in to the wealth of community violence prevention programs on offer.

"This city has more resources than any of the ones I've been in," Humphrey said, but that it was frustrating to not see more people make use of those services.

The city has spent millions of dollars a year for decades providing community violence reduction programs, Scott said.

"We have the resources, we are committing the resources," Scott said, but people have to get involved in the community programs for them to pay off.

Humphrey mentioned one of the people arrested as a suspect in a homicide last week as an example of a teen in the city who fell through the cracks, although he didn't name the person.

That person, by age 17, was already on the police's radar, and they had tried to provide community services for him, Humphrey said. But in his case, that didn't work, with Humphrey calling the young man "broken," someone who had done irreparable harm through their violent actions.

One of the ways the department is trying to do more is by offering the services of social workers, Humphrey said. The department recently hired two part-time social workers in addition to the single full-time worker and a number of interns. There is now a social worker at each of the agency's three division headquarters.

"We've never had anything like this," said Maj. Andre Dyer, head of the 12th Street patrol division, a 27-year force veteran.

Dyer described mothers in tears because their children had been able to get "the help they did not think was available to them" from a police department they thought wasn't on their side.

Cole, the police lieutenant, was asked to join Saturday's panel because of his role with much of the department's community programs, including a several-week-long program where they teach teens about cooking, he said.

This year, that program drew 30 attendees when they expected 10, Cole said. In recent weeks, he was also involved in a community program feeding as many as 200 homeless people at the Compassion Center.

Valerie Tatum, a retired teacher, said it meant a lot to her to see a white police officer being truly involved in majority-Black communities, listening to people's problems and attending community meetings.

Saturday's panel discussion was the third in the Courageous Conversations series, and the officials have now had these meetings all across the city, across different police patrol divisions. As of Saturday, no plans had been announced for more of the town halls.