An agreement signed on Wednesday will allow citizens of the Cherokee Nation to gather 76 species of culturally significant plants from the Buffalo National River park in Arkansas for traditional use.

The list includes a wide variety of vascular plants, from "Arkansas Tumble Weed" to "Wild (Possum) Grapes."

Normally, the removal of plants from a National Park is against federal law. But a 2016 rule, 36 CFR 2.6, allows park superintendents to make such agreements with American Indian tribes.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said climate change threatens the availability of the tribe's traditional medicinal plants in Oklahoma.

But some of the plants are plentiful three hours to the east at the Buffalo National River.

"There are so many pressures on Cherokee culture over the centuries since European contact," Hoskin said during a signing ceremony in Tahlequah, Okla., on Wednesday. "Certainly that includes pressure on our language and culture that has eroded so much of our lifeways. Certainly modern pressures such as climate change threaten medicinal plants across our reservation as they do for native peoples around the world. So it's important that Cherokee Nation takes steps to protect, in particular, medicinal plants because the knowledge of those plants is something that is in scarce supply these days."

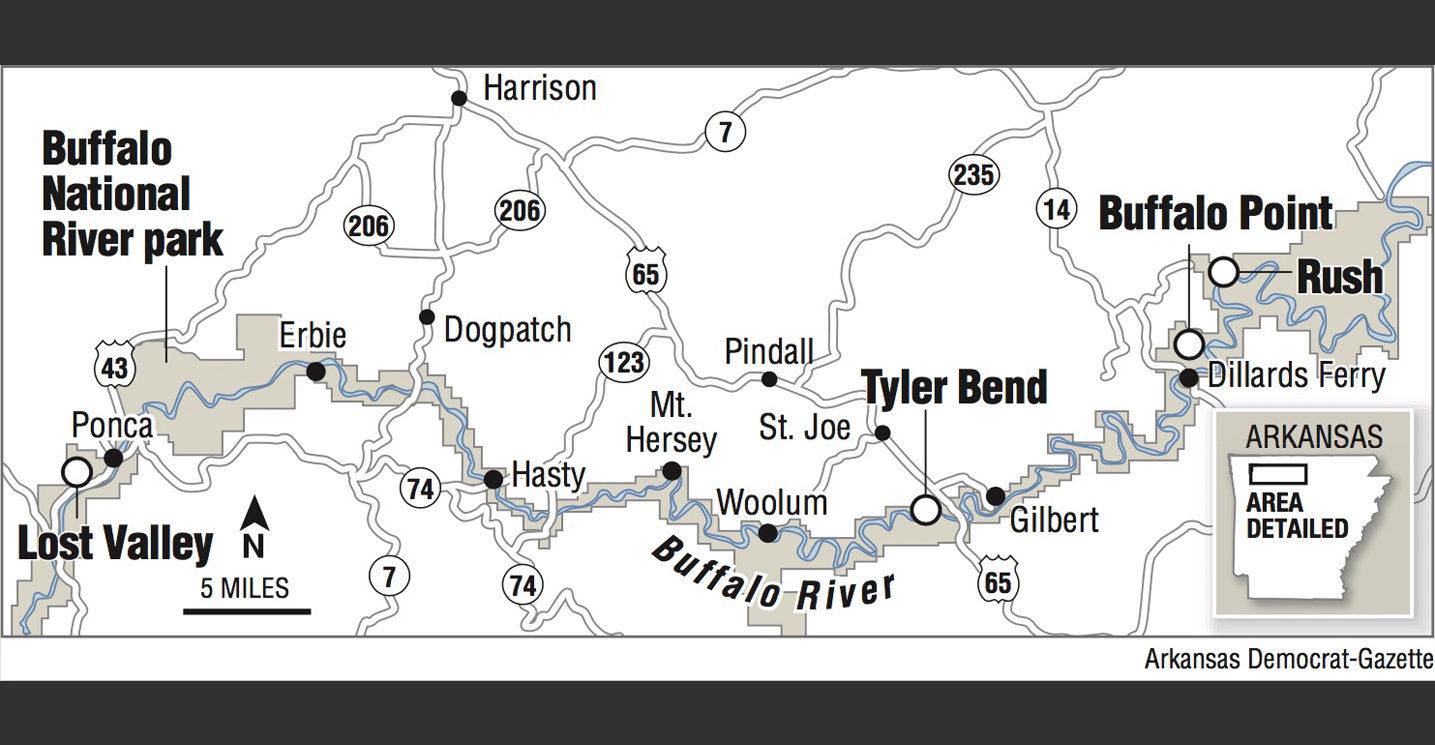

The agreement says the tribe will establish a process for its citizens to gather 76 traditional plants in certain areas of the Buffalo National River park including the Lost Valley, Tyler Bend, Buffalo Point and Rush areas.

Only members of the Cherokee Medicine Keepers are allowed to gather plants at the Arkansas park at this time, according to the agreement. The Medicine Keepers is a group of tribal members who help preserve cultural traditions and pass them down to younger generations.

Chad Harsha, secretary of natural resources for the Cherokee Nation, said individual tribal members will be allowed to go to the Arkansas park to gather plants after the process is put into place. He said it would require filling out an application through a Cherokee Nation computer portal.

"The Cherokee Nation will provide the names of those enrolled members authorized to gather plants or plant parts to the Park prior to any gathering activity," according to the agreement. "These authorized plant gatherers will be identified on the annual Special Use Permit issued by the Park for the gathering activity. During gathering activities, authorized gatherers will be identified by tribal ID issued by the Cherokee Nation, accompanied by a copy of the Special Use Permit issued by [Buffalo National River] and received by the Cherokee Nation."

Mark Foust, superintendent of the Arkansas park, also spoke at Wednesday's event.

"It's very fitting I think that this is the 50th anniversary year of Buffalo National River," he said. "But we know in the National Park Service that many came before us as stewards of this land. So our ability to partner with the Cherokee Nation and steward the land that you cared for, and the Medicine Keepers know so well, is truly our honor. So we thank you and we look forward to many, many years of working together and really working hard to protect the ecosystem for the next generation and the generations after that."

Besides the agreement with the Buffalo National River, Hoskin also signed an executive order setting aside almost 1,000 acres of land inside the Cherokee Nation Reservation as the Cherokee Medicine Keepers Preserve.

Clint Carroll, associate professor of ethnic studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said talks between the Cherokee Nation and the Buffalo National River began in 2014. He and others took a field trip to the park in 2017 to survey the plants there. Plans were to sign the agreement with the park superintendent in 2020, but the pandemic put things on hold.

Carroll, who is a member of the Cherokee tribe, said the first trip to the Buffalo National River to gather plants is scheduled for October. He said five students in the Cherokee Environmental Leadership Program will accompany the Medicine Keepers and learn from them the traditions associated with plant gathering.

Carroll said tribal members are somewhat guarded about their medicinal plants because they are collected and used in sacred rituals. He said it's to protect people who don't know how to use the plants.

"Cherokee plant medicine includes not only the chemical properties of plants that act as 'medicine,' but also the faith and spirituality of the patient and healer," Carroll wrote in 2020 for "Parks Stewardship Forum," a conservation journal. "This is why it is especially important to revitalize Cherokee plant knowledge -- because, in turn, it revitalizes a way of life centered on spirituality and relationships to the land and cosmos."

Regarding climate change, in the same publication, Carroll wrote, "The Cherokee Nation is located at the confluence of two vastly different climate zones -- to the west, a semi-arid tallgrass prairie zone, and to the east, an eastern deciduous forest zone. Documented and projected rising temperatures, along with landscape fragmentation caused by human activities, are creating significant stress on native plant habitats across the Great Plains and the Southeast."

According to a 2019 environmental assessment, the 76 species "would be harvested at different times of year as the plant parts of focus reach their optimal time for harvest."

Based on 36 CFR 2.6, the agreement automatically expires in five years.

"Prior to the approval of a renewed agreement, this agreement will be reviewed by the Cherokee Nation and BNR to identify any potential areas for improvement," according to the environmental assessment.

A paragraph in the agreement noted the Cherokee Nation's relationship with Arkansas.

"The Cherokee Nation's traditional association to the area of the Buffalo River dates back to the early eighteenth century when Cherokee people were migrating westward due to increasing encroachments upon their southeastern homelands by Euro-American settlers," according to the agreement. "This group of Cherokees, often referred to as the Old Settlers, sought to avoid conflict with Euro-American people by establishing new settlements west of the Mississippi River. During this time, Cherokees continued ways of life that included the use of wild plants for food, tools, utilities, and medicine.

"Due to the similarity of the Ozarks to their southeastern homelands, Cherokee people were able to use many of the same plants they had previously known and cherished. Today, Cherokee people use these plants to sustain our connection to the land and to perpetuate cultural lifeways that are inseparable from the natural world. These uses include food from wild greens, nuts, and berries; crafts from bushes, trees, and cane; and medicine from the many leaves, barks, and roots of the forests and fields."

In his journal article, Carroll wrote that "the agreement represents an acknowledgement of the troubled history of the National Park Service, and can be seen as an attempt to right historical grievances."

"As scholars have increasingly emphasized, the early conservation movement in the United States often entailed removing Native peoples from their homelands in order to create what are now known as national parks," wrote Carroll. "This process, known as 'conservation enclosure,' coincided with the establishment of Indian reservations throughout the country, and marked both a physical and philosophical separation between humans and "nature" in the United States. Although this period is commonly celebrated for its protection of national lands and resources, when viewed through the eyes of Indigenous peoples, the park system embodies yet another story of dispossession.

"Nevertheless, national parks have played an important role in protecting lands and resources from exploitation. This situation indicates an unusually fortunate paradox: that although the formation of many national parks entailed forcibly relocating Native people from their homelands and ancestral areas, the park system has ensured that those lands remain relatively untouched from the detrimental effects of development and environmental contamination that plague many tribal lands today."