WASHINGTON -- Shoes off, an almost-empty container of leftovers, an unfinished glass of wine -- this was the exhausted portrait of one of the most powerful Democrats in Washington after Senate passage of President Joe Biden's sweeping health, climate and economic package.

New York's Charles Schumer effectively moved from minority to majority leader of the U.S. Senate on the morning of the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol insurrection, and he has helmed the chamber through a tumultuous, messy and yet surprisingly productive run with the longest evenly split 50-50 Senate in the nation's history.

Methodical he is not, as the crumbs scattered on the senatorial carpet in his office off the Senate floor attest.

But with a willingness to broker politically unpleasant compromises and a New Yorker's drive to keep pestering his colleagues, Schumer is using his party's fragile control of the Senate for substantive, sizable accomplishments unseen in recent years.

"Persistence. I persist," Schumer said in an interview late Sunday evening after the round-the-clock session and Senate passage of Biden's bill.

The $740 billion package, less than once envisioned but still huge, would be a big legislative win for any president and his party. For Biden and the Democrats, it builds on long-running aspirations of lowering health care costs, taxing big corporations that skip paying their share and launching the nation's largest investment, some $375 billion, to fight climate change. With revenue raised from corporate taxes and allowing the federal government to negotiate some prescription drug costs with pharmaceutical companies, the remaining $300 billion goes to deficit reduction.

Not everyone is cheering Schumer.

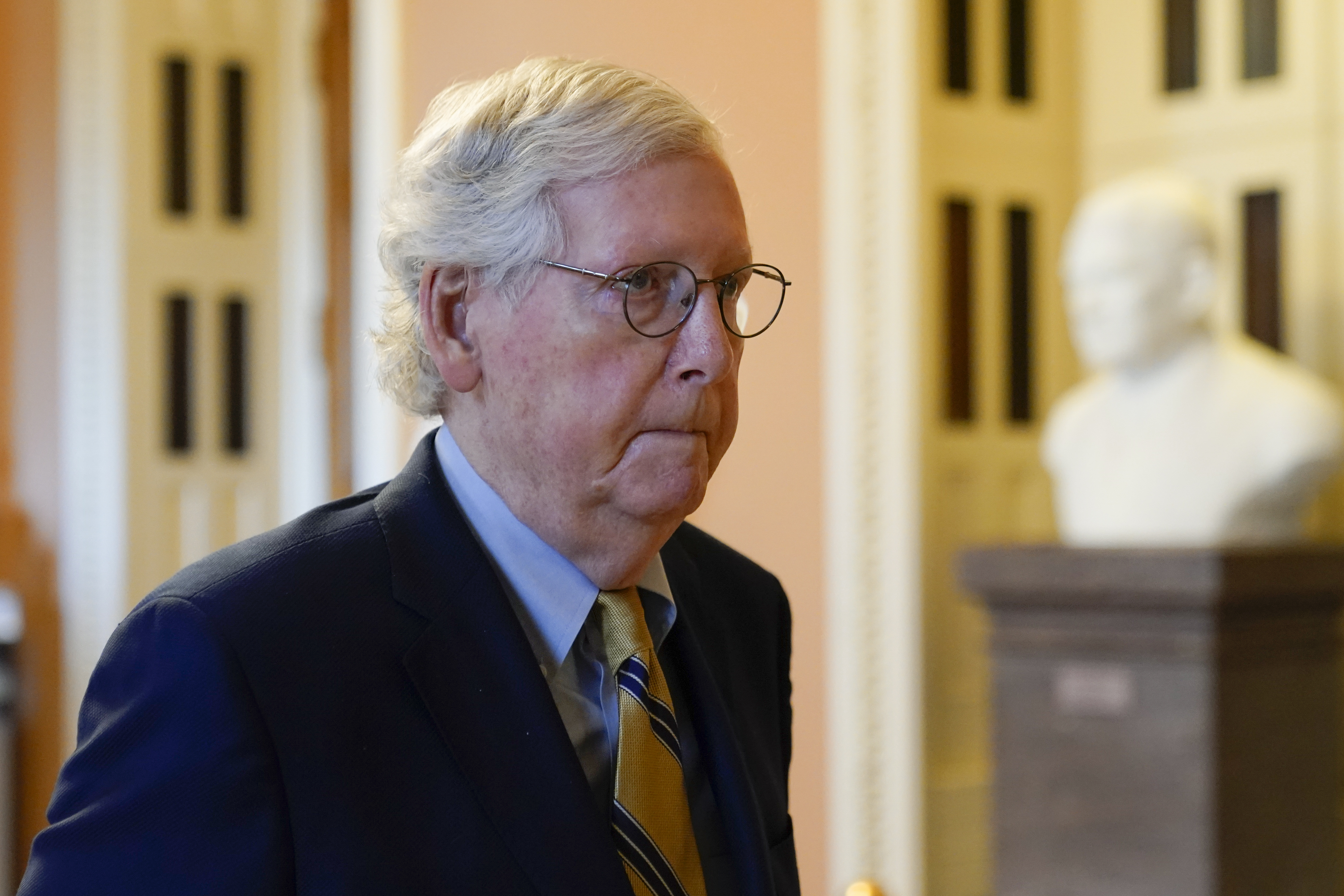

Republicans deride the Democrats' effort as "yet another reckless taxing-and-spending spree," as Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky put it. Over the weekend, he argued that the Democrats have mistaken their slim control, with Vice President Kamala Harris able to cast a tie-breaking vote, as a mandate for far-reaching policy goals.

"This bill is a true Trojan Horse with long-range negative effects on U.S. business and consumers as well. Chief among the misdirections in the bill are the minimum corporate tax to be imposed on large businesses and the drastic increase in the size of the IRS agency," Randy Zook, president and CEO of the Arkansas State Chamber/Associated Industries of Arkansas, said in statement.

"We are continuing to study the bill and expect to find more egregious matters in the fine print," Zook said. "For now," he added, "we have found plenty of reasons to oppose the bill and urge Arkansas' Congressmen to follow the example of our Senators and say no to this overwhelming and incredibly costly bill."

And the 755-page bill comes on top of a string of similarly pared-back initiatives, deep disappointments for the party's liberal wing. But some have been backed by Republicans with rare bipartisan accord, adding up to a Congress with unexpected gains.

The toughest gun violence measure in a generation, a bipartisan effort to tighten who can own guns, is now law. This week Biden is about to sign into law a $280 billion bipartisan bill to boost the semiconductor industry as well as a nearly $300 billion measure to help veterans exposed to toxic burn pits.

By themselves, Democrats muscled through a $1 trillion covid-aid package that McConnell calls a buffet of "all-you-can-eat liberal spending." But McConnell and Republicans joined Schumer in passing the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill for the nation's roads, broadband and other needs.

In addition to legislation, over the past 18 months under Schumer's leadership the Senate held the nation's fourth-ever presidential impeachment trial, eventually acquitting Donald Trump on charges that he incited the Capitol insurrection; ratified the accession of Finland and Sweden to join NATO; and confirmed the first Black woman, Ketanji Brown Jackson, as a justice to the U.S. Supreme Court.

"This is the longest there's ever been an evenly divided Senate, and it is a real tribute to leader Schumer that he has managed to corral all 50 Democrats behind a legislative agenda," said Sen. Chris Coons, the Delaware Democrat.

Unlike previous highly productive sessions of Congress, Schumer does not enjoy the big majorities typically required to get work done. The filibuster tradition, with its 60-vote threshold to advance most measures, is a powerful tool wielded by McConnell and Republicans (and Democrats, when they are the minority party) that can block almost any initiative.

With zero room for error, Schumer has relied on a vital skill -- talking.

When he first became Democratic leader, in the minority then, he famously expanded his leadership team to include almost half the caucus, ensuring all segments -- from Bernie Sanders on the left to Joe Manchin more to the right -- had a seat at the table. His flip-phone has become such an integral part of his communication strategy that Schumer now holds it up as a prop, a reminder of how he works.

And then there are the dinners.

After Manchin abruptly walked away from talks with Biden over the party's original Build Back Better proposal, Schumer invited the West Virginia senator out to dinner.

"I said look, Joe, we have to get something done here," Schumer recalled.

Over spaghetti and meatballs the day after Valentine's Day at an Italian restaurant on Capitol Hill, Schumer got down to business.

"And I said, Look, you have a lot of clout here. You proved you're willing to stop the whole thing. But I got to get 49 senators to vote on this. This can't just be what you want," Schumer told the former governor he had recruited to run for the Senate a decade ago. "There's got to be a compromise."

That willingness by Schumer to take the political bad with the good -- in Manchin's case, the coal-state senator's insistence on policies for the oil and gas industry that liberals deplore -- infuriates liberals and somewhat threatens Schumer's hold on power.

Sanders lambasted the final package as insufficient, even as he voted for it, and Sanders' fellow progressive Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has been eyed as a powerful New York Democrat who could one day challenge Schumer in a primary election. There are several senators who could imagine themselves as the majority leader someday.

Schumer's view: "My job is to get things done."

"It's very easy to be a Mitch McConnell," he said about the Republican who prided himself on sending to the "graveyard" bills from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's Democrats when he was majority leader.

"It's easy to stop things, particularly in a Senate that's designed to stop things. It's hard to get things done."

RALLYING CRY

President Joe Biden raised the final pillar of his economic agenda with the Senate's passage of a breakthrough climate and tax package, sealing a legacy that risks being undermined by an inflation surge he's blamed for sparking.

The success of the Inflation Reduction Act will give Democrats a rallying cry for midterm elections and joins three other key bills as a foundation of what might be called Bidenomics: a combined $3 trillion push to reshape the U.S. economy toward working families and domestic manufacturing, boost competition against China and avert the kind of stunted recovery Biden saw as vice president.

While the results in the later bills are more modest than the big structural changes and spending plans Biden had sought -- the most recent is a fraction of his Build Back Better proposal -- they're still greater than what seemed possible over much of the past year as potential deals were repeatedly scuttled, at times by senators from his own party.

The risk now is that inflation, partly blamed on Biden's first big steps in the outsized $1.9 trillion covid-aid package, will end up confining him to a one-term presidency.

"This could be read as the best supply-side economics program since Eisenhower built the interstate highway system," said Alan Blinder, a former Fed vice chairman and adviser in Bill Clinton's White House, referring to the post-World War II road-building boom credited with feeding decades of growth. But as for a political payoff: "It's a stretch unless and until inflation starts coming down," he said.

The Inflation Reduction Act, expected to win final passage with a House vote Friday, comes on the heels of a bill offering subsidies to the semiconductor industry, which Congress approved with bipartisan votes last month. A bipartisan long-term infrastructure package was enacted in November. The American Rescue Plan passed in March 2021.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen termed the administration's vision as "modern supply-side economics," evoking the supply side theory most often associated with President Ronald Reagan.

But Biden described it as aimed at building the economy from "the bottom up and the middle out," speaking to the sweeping reinvigoration of social investments in families aimed at reducing inequality.

Unlike the Republican supply-side agenda of cutting taxes to boost productivity, Bidenomics offers government investments and incentives for domestic output, along with social support to bring more people into the labor market -- while reducing environmental damage.

"They're all working to build connectivity tissue between overall economic growth and prosperity for working families," Jared Bernstein, a White House economist and longtime Biden aide, said of the economic legislation. "If you're helping to bake the pie, you ought to get a fair slice."

Job one after taking office was fighting the pandemic and its economic fallout with a more powerful response than Biden and then-President Barack Obama oversaw more than a decade before. The $787 billion package approved in 2009 is now regarded by many as having done too little to pull the U.S. out of the Great Recession.

The kind of scarring endured in the 2010s has indeed been avoided. Unemployment has plunged from nearly 15% in April 2020 to 3.5% now, matching a half-century low. Wages also surged back; the lowest-earning quarter of the wage scale has even roughly kept pace with inflation.

But the biggest surge in the cost of living in four decades has meant most households have endured a decline in purchasing power -- leaving them without what Biden says he was trying to give: "breathing room."

Economists estimate the cash handouts in the March 2021 pandemic-relief bill caused between one-half and three percentage points of the current inflation readings of 9.1% -- the highest in the Group of Seven and the worst since the stagflation misery a generation ago. The White House argues that the impact was less than that.

The irony is that those cash handouts were a necessary political ingredient for achieving the rest of the economic legislation. Back in January 2021, control of the Senate hinged on a pair Senate runoff elections in Georgia, where stimulus checks were a core issue.

Democrats won on an explicit pledge to send more money to households enduring a grueling pandemic. That gave them the congressional control that likely enabled passage of the other three bills.

While economists attribute most of the inflation jump to pandemic-related global supply-chain issues and the impact on fuel and food prices from Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Americans have effectively blamed Biden.

The president's approval rating fell to 38% in Gallup's July tracking, its lowest yet, and it may worsen if the Federal Reserves's aggressive rate hikes tip a slowing economy into a job-killing recession.

NO SALT, NO DEAL

The House Democrats who had threatened to block President Joe Biden's tax and climate plan unless it also expanded the deduction for state and local taxes are now signaling they'll back the legislation when it comes up for a vote later this week.

Representatives Josh Gottheimer, Tom Suozzi and Mikie Sherrill, who have led efforts for months to include an increase to the $10,000 cap on deductions for state and local tax, or SALT, said they will vote for the tax and climate bill passed by the Senate on Sunday even though it doesn't address the write-off.

"Because this legislation does not raise taxes on families in my district, but in fact significantly lowers their costs, I will be voting for it," Sherrill of New Jersey said in a statement.

Gottheimer, also of New Jersey, said that his "line in the sand remains the same" on SALT, and he will insist that it is included in any future bill that would increase taxes for households in his district. New York's Suozzi also supports the bill.

The lack of opposition from the self-dubbed "No SALT, no deal" caucus eliminates nearly all doubt that House Democrats will pass the legislation. Progressive Democrats, who had been pressing for more aggressive measures on climate also have indicated they'll back the $437 billion package.

The Senate-passed bill included several business tax increases, including a 15% minimum tax on corporations, a stock buyback tax and an extension of a provision that limits how much in losses pass-through entities can write off in a given year. Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, the moderate Democrats who shaped much of the bill, rejected many of the tax proposals initially made by Biden.

For months, Democrats pushing for SALT had threatened to tank the bill if it failed to include the valuable tax break, which largely benefits residents of high-tax states in the Northeast and West Coast. The House passed a version of the bill last year that raised the deduction cap to $80,000 from $10,000 per household. However, after much of the bill was stripped to win over Sinema and Manchin, Democrats were essentially forced to accept the legislation as-is.

The $10,000 SALT cap was imposed starting in 2018 as a way to pay for some of the levy cuts in former President Donald Trump's tax cut law. Democrats say the measure was intended to target voters in states that voted against Trump. The SALT cap expires at the end of 2025 and reverts back to unlimited deductions then, unless Congress passes another law addressing it.

Information for this article was contributed by Lisa Mascaro of The Associated Press and by Josh Wingrove, Christopher Condon and Laura Davison of Bloomberg (WPNS).

FILE - Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Ky. walks to his office on Capitol Hill in Washington, Saturday, Aug. 6, 2022. Democrats pushed their election-year economic package to Senate passage Sunday, Aug. 7, 2022, a compromise less ambitious than Biden’s original domestic vision but one that still meets party goals of slowing global warming, moderating pharmaceutical costs and taxing immense corporations. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

FILE - Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Ky. walks to his office on Capitol Hill in Washington, Saturday, Aug. 6, 2022. Democrats pushed their election-year economic package to Senate passage Sunday, Aug. 7, 2022, a compromise less ambitious than Biden’s original domestic vision but one that still meets party goals of slowing global warming, moderating pharmaceutical costs and taxing immense corporations. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File) Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., speaks to reporters at the Capitol in Washington, Aug. 1, 2022. Republicans see inflation, taxes and immigration as Democratic weak spots worth attacking, and two opposition senators as prime targets, in the upcoming battle over an economic package the Democrats want to push through the Senate. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., speaks to reporters at the Capitol in Washington, Aug. 1, 2022. Republicans see inflation, taxes and immigration as Democratic weak spots worth attacking, and two opposition senators as prime targets, in the upcoming battle over an economic package the Democrats want to push through the Senate. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite) FILE -Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., speaks to reporters after a closed-door policy meeting, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, Aug. 2, 2022. Schumer effectively became the leader of the U.S. Senate on the morning of the Jan. 6, 2021 Capitol insurrection. And it has been mess and tumultuous ever since. Yet the New York Democrat has led the Senate in a surprisingly productive run, despite the longest evenly split 50-50 Senate in U.S. history. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

FILE -Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., speaks to reporters after a closed-door policy meeting, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, Aug. 2, 2022. Schumer effectively became the leader of the U.S. Senate on the morning of the Jan. 6, 2021 Capitol insurrection. And it has been mess and tumultuous ever since. Yet the New York Democrat has led the Senate in a surprisingly productive run, despite the longest evenly split 50-50 Senate in U.S. history. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)