When Enrique Romero Jr. finishes his shift fulfilling online orders at a Fred Meyer grocery store in Bellingham, Wash., he often walks to a nearby plasma donation center. There, he has his blood drained, and a hydrating solution is pumped into his veins, which leaves him tired and cold.

Romero, 30, said selling his plasma made him feel "like cattle." But the income he earns from it -- roughly $500 a month -- is more reliable than his wages at Fred Meyer, which is owned by grocery giant Kroger. His part-time hours often fluctuate, and he struggles to find enough money to cover his rent, groceries and the regular repairs required to keep his car on the road.

"The economy we have is grueling," he said.

Business has boomed during the pandemic for Kroger, the biggest supermarket chain in the United States and the fourth-largest employer in the Fortune 500. It owns more than 2,700 locations, and its brands include Harris Teeter, Fred Meyer, Ralphs, Smith's, Pick 'n Save and even Murray's Cheese in New York City. The company, based in Cincinnati, said in December that it was expecting sales growth of at least 13.7% over two years. The company's stock has risen about 36% over the past year.

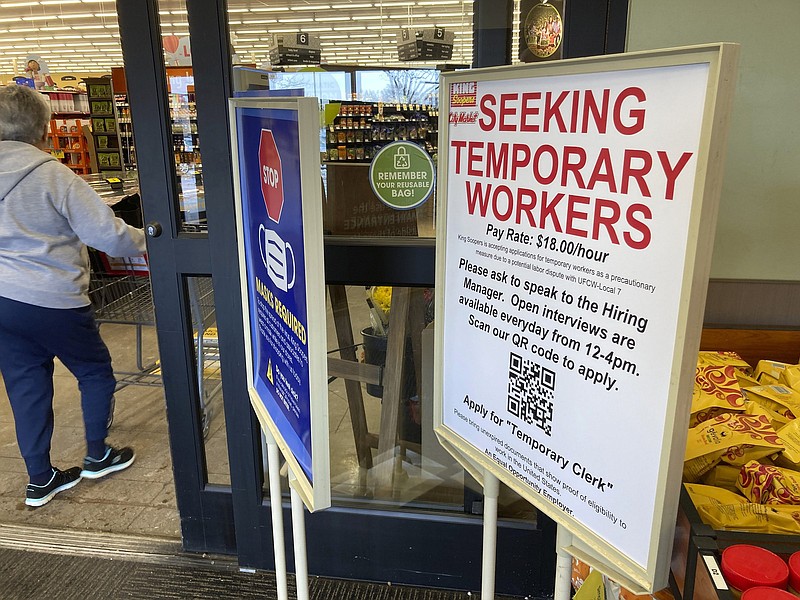

A brief strike in Colorado last month by workers -- represented by the United Food and Commercial Workers Union -- at dozens of Kroger-owned King Soopers locations brought renewed scrutiny to the issues of pay and working conditions for grocery workers, who have been on the front lines throughout the pandemic.

"There is a race to the bottom that's been going on for a while with Walmart and other large retail stores, and also restaurants, and to reverse that trend is not easy," said Daniel Flaming, president of the Economic Roundtable.

The Economic Roundtable, a nonprofit research group, surveyed more than 10,000 Kroger workers in Washington, Colorado and Southern California for a report commissioned by four units of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union. The group said Kroger was the sole employer for 86% of those surveyed, partly because more than half had schedules that changed at least every week, making it difficult to commit to another employer. About two-thirds said they were part-time workers, even though they wanted more hours. Sixty-three percent said they did not earn enough money to pay for basic expenses every month.

KROGER REACTION

Kristal Howard, a spokeswoman for Kroger, said the report was "one-dimensional and does not tell the complete story."

"Kroger has provided an incredible number of people with their first job, second chances and lifelong careers, and we're proud to play this role in our communities," she said. Howard added that the company had raised its national average hourly rate of pay to $16.68 from $13.66 in 2017, a 22% increase, and that its benefits package included health care, retirement savings, tuition assistance and on-demand access to mental health assistance.

Some of the workers said that even though other retailers and fast-food restaurants had started offering higher starting wages than Kroger, the company's health insurance and retirement benefits, which the union negotiated, were more generous than what other employers offered. Other part-time Kroger workers say they stay on the job because they don't want to lose their seniority and the chance for a full-time role.

Despite some of the wage increases and benefits, working at a grocery store no longer provides the stable income and middle-class lifestyle that it did 30 years ago, workers say. The Economic Roundtable report studied contracts dating back to 1990 and said the most-experienced clerks -- known as journeymen -- in Southern California made roughly $28 per hour in today's dollars while working full-time schedules. Wages for top-paid clerks today are 22% lower, and those workers are far more likely to be working part-time hours, the group said.

'POVERTY LEVEL'

Ashley Manning, a 32-year-old floral manager at a Ralphs in San Pedro, Calif., works full time but is regularly strapped for cash. Manning, the single mother of a 12-year-old, said she had worked at Ralphs for nine years and earned $18.25 an hour. It took her four years to reach full-time status, which guarantees 40 hours a week and comes with an annual bonus ranging from $500 to $3,000.

She said she struggled to pay rent and moved into her grandmother's house after being evicted last spring. She has needed help from her family to help pay for a car.

"I would think, 'I have a good job and make decent money,' and I don't," Manning said. "I'm still on the poverty level."

During the pandemic, grocery store workers have been recognized as essential to keeping society going, but they have also faced health risks. At least 50,600 grocery workers around the country have been infected with or exposed to the coronavirus, and at least 213 have died from the virus, according to the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union.

Manning was hospitalized for covid-19 last summer. She blames herself for her grandmother's subsequent death from the virus in August.

Kroger has one of the country's biggest gaps between a chief executive officer's compensation and that of the median employee. Rodney McMullen, Kroger's CEO since 2014, earned $22.4 million in 2020, while the median employee earned $24,617 -- a ratio of 909-to-1. The average CEO-to-worker pay ratio in the S&P 500 is 299-to-1, with grocery chains such as Costco (193-to-1) and Publix (153-to-1) lower than that.