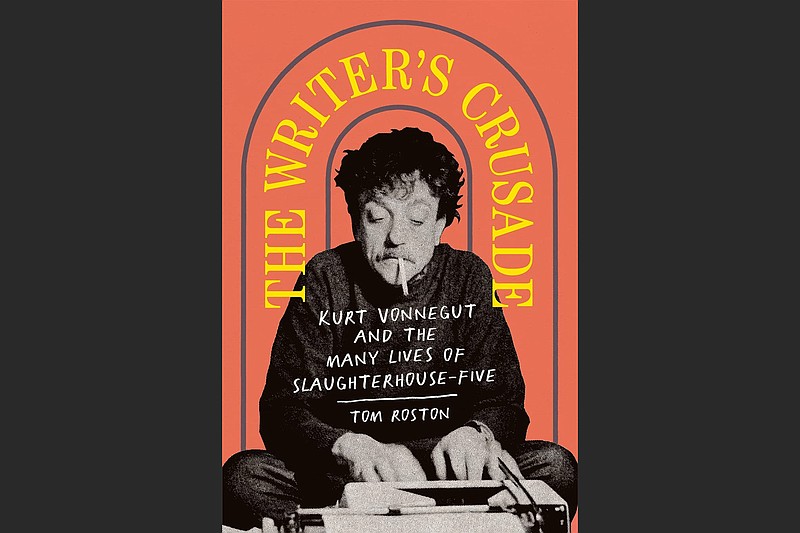

In his new book "The Writer's Crusade: Kurt Vonnegut and the Many Lives of Slaughterhouse-Five" (Abrams Books, $26), Tom Roston posits that author Vonnegut may have — probably — suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

If you are familiar with Vonnegut's life and work, particularly his most famous (and probably best) novel "Slaughterhouse-Five," your response might be well, of course he did.

Vonnegut is almost as famous for having been taken prisoner by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge and having witnessed the firebombing of Dresden while being held in a work camp as he is for having written a handful of well- regarded and wildly popular novels, a few of which ( "Slaughterhouse," "Breakfast of Champions," "Cat's Cradle" and "Mother Night") have entered the American canon.

Vonnegut didn't believe this was his fault. He thought you could only write the stuff you were supposed to write; whether other people responded to it or not was beyond your control.

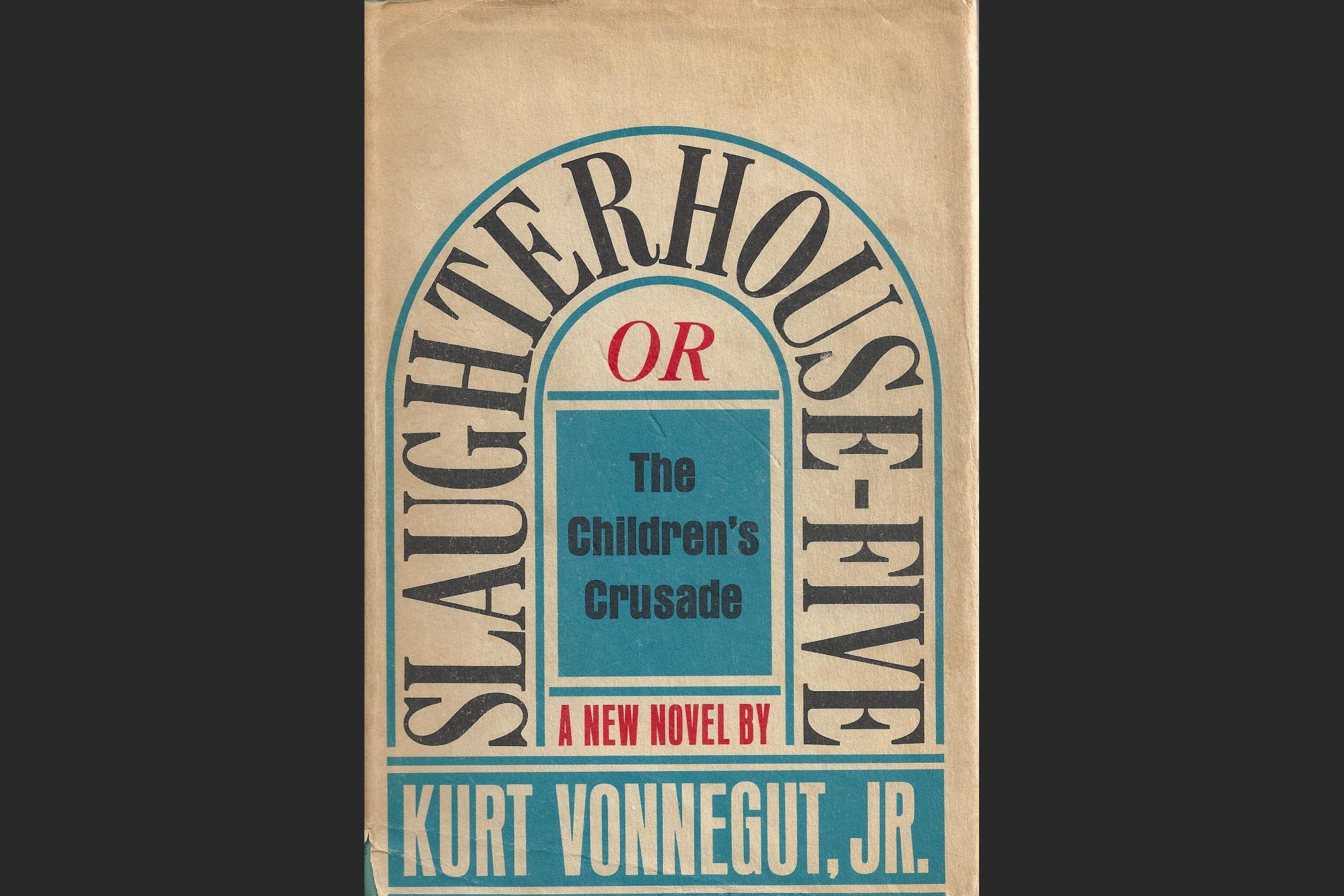

"Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death" is about American soldier Billy Pilgrim, a chaplain's assistant during World War II who is captured by the German Army during World War II and sent to a forced labor camp in Dresden.

Billy and his fellow prisoners are held in an empty slaughterhouse called Schlachthof-funf ("slaughterhouse five"). During the extensive carpet bombing of Dresden in February 1945 by the British and Americans, German guards take shelter among the prisoners because the slaughterhouse is partially underground and relatively well-protected from the bombs. So they are among the few survivors.

In May, after the surrender of the Nazis, Billy is sent home, where he is hospitalized with shell shock. He later goes on to become a wealthy optometrist. In 1949, Billy is abducted by a flying saucer and taken to Tralfamadore, a planet light-years away from Earth, where he is placed in a transparent geodesic dome exhibit in a zoo. Later the aliens abduct porn star Montana Wildhack to serve as Billy's mate. They fall in love, they have a child.

The story is told in a nonchronological fashion, which dovetails with its central conceit — that Billy Pilgrim has become unstuck in time. He travels back and forth, reliving various episodes in his life. Not even his death — which will always occur on Feb. 13, 1976 — provides him with escape.

As one of his Tralfamadorian hosts tells him: "All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is. Take it moment by moment, and you will find that we are all, as I've said before, bugs in amber."

When Billy responds that this seems like the alien doesn't believe in free will, the Tralfamadorian responds:

"If I hadn't spent so much time studying Earthlings, I wouldn't have any idea what was meant by 'free will.' I've visited 31 inhabited planets in the universe, and I have studied reports on 100 more. Only on Earth is there any talk of free will."

Billy's wartime experiences mirror Kurt Vonnegut's. When Vonnegut was 20 years old, he enlisted in the United States Army. Less than two years later, he was captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge. Like Billy Pilgrim he was held in a slaughterhouse called Schlachthof-funf where he survived the horrific firebombing that killed thousands and destroyed the city.

According to "Slaughterhouse-Five," Vonnegut was standing next to Billy Pilgrim when the doors of the boxcar bringing the POWs to Dresden opened on the city — "the Florence of the Elbe." Billy thought it "looked like a Sunday School picture of Heaven." The prisoner next to him assessed it with a single word: "Oz."

"That was I," Vonnegut writes. "That was me. The only other city I'd ever seen was Indianapolis, Ind."

Vonnegut was born in November 1922 in Indianapolis. His father was an architect, his mother heir to a brewery fortune. But they were humbled by Prohibition and the Great Depression, and the family struggled. Young Kurt was taken out of private school, the family home was sold.

Vonnegut was born in November 1922 in Indianapolis. His father was an architect, his mother heir to a brewery fortune. But they were humbled by Prohibition and the Great Depression, and the family struggled. Young Kurt was taken out of private school, the family home was sold.

Vonnegut went off to college at Cornell, but dropped out after being placed on academic probation and enlisted in the Army in May 1943. He eventually was assigned to military training in Edinburgh, Ind., close enough to his family that he was able to sleep in his old bedroom on weekends. He trained as an infantry scout, in anticipation of an Allied invasion of Europe.

On Mother's Day 1944, he came home from training to find his mother dead; she had committed suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills.

"I only wish she'd lived to see [my writing career]," Vonnegut told the Paris Review years later. "I only wish she'd lived to see all her grandchildren."

Vonnegut himself would attempt suicide in a similar manner in 1984.

"Maybe he had PTSD from just being alive," Roston quotes Vonnegut's daughter, the painter Edith Vonnegut, as saying. "He saw too much. And he felt too much."

■ ■ ■

Even though Vonnegut always insisted (protested?) that he had not been traumatized by his wartime experiences, we might suspect that he was changed by seeing terrible things. (He said seeing terrible things made him "thoughtful.")

There is profound sadness and resigned bitterness in his work. Vonnegut was a desperate humanist who seemed to believe at bottom that, as a species, human beings were just no damn good. All we could do was mitigate the pain through loving each other until the eye closed off forever.

Whether or not Vonnegut suffered from something that could be clinically defined as PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) seems irrelevant. He survived and witnessed and was battered by life. And, like most of us, he possessed a certain empathy. He was sensitive to the pain of others.

That empathy informed his writing to a great degree and is likely the prime reason he is beloved by so many. Vonnegut prescribed kindness, and that's why the highest and best use of his work may be to serve as a corrective for an adolescent mind fired up by exposure to Ayn Rand's "The Fountainhead" or "Atlas Shrugged." (For every dose of Randian Objectivism, read some Vonnegut to keep humble.)

But fortunately, Roston realizes, and even comments on, the vulgar nature of his enterprise, which he says is to "answer whether or not 'Slaughterhouse-Five' can be used as evidence of its author's undiagnosed PTSD."

"I imagine reducing his book to a clinical diagnosis, or perhaps worse, putting it in the self-help category, would make Vonnegut shudder," he writes. Indeed.

What's most valuable about Roston's book — it is valuable, though it feels a bit like an expanded version of a clever student's school paper in which facts are marshalled to support a handy, hooky hypothesis — is his research, his interviews with scholars and Vonnegut "devotees" like writer Steve Almond, whose 17,000-word essay on Vonnegut and his work, "Everything Was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt," remains one of the most insightful deconstructions of Vonnegut's appeal.

"The main thing was that Vonnegut made an impact on readers," Almond wrote. "He wasn't one of those recluses who hid behind coy fictional guises. Every sentence he wrote, every character, was stamped in his image. He came clean on the page as a guy losing his s***...

"He was honest about why he wrote, too. He copped to that central (if rarely mentioned) impulse of the writing life: he wanted attention. He spoke bluntly, courageously, about prevailing injustices, not just on the page, but in public. He was funny, self-deprecating, easy to read, a (gasp) populist. He wanted to speak to everyone and he wanted everyone to shape the hell up. He hated rich people and warmongers and fanatics. He didn't pretend not to care."

Roston notes that Almond, like a lot of Vonnegut fans, perceived the writer's work as authentic, that part of "Slaughterhouse-Five's" appeal "is that [they] seamlessly identify with both the protagonist and his creator because it feels like nonfiction."

"This is what it feels to be me," Roston quotes Almond as saying. "This is not just a writer pulling something out of his bag of tricks. He understands me. And it's a by-product of his traumatic history."

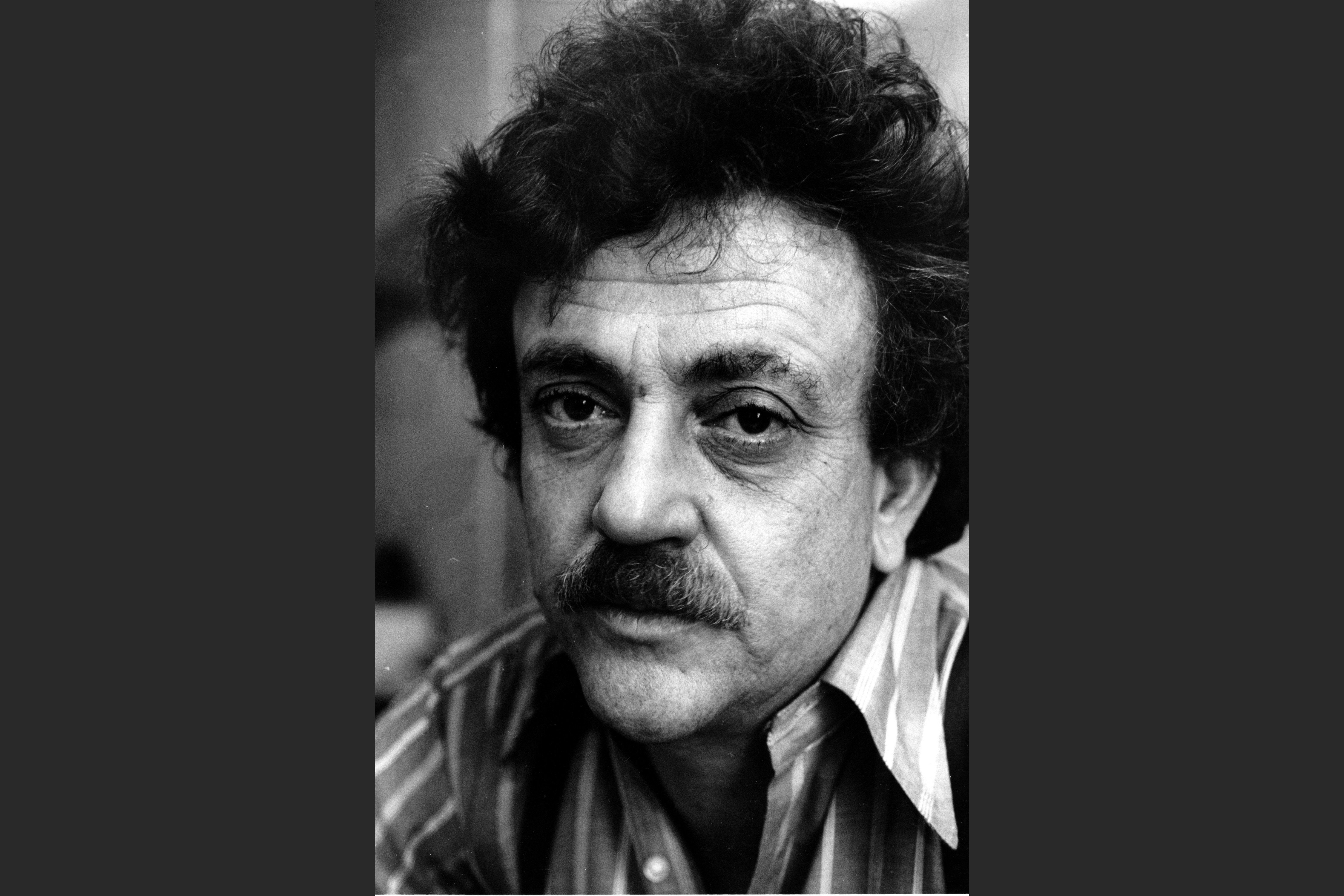

Kurt Vonnegut on Nov. 24, 1971 (AP file photo)

Kurt Vonnegut on Nov. 24, 1971 (AP file photo)

The idea of "Slaughterhouse-Five" as a novel that explores PTSD is hardly a new one; it probably dates back to when the novel was published in 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War. On the occasion of the novel's 50th anniversary, Salman Rushdie gave a talk where he observed, "It is perfectly possible, perhaps even sensible, to read Billy Pilgrim's entire Tralfamadorian experience as a fantastic, traumatic disorder brought about by his wartime experiences — as 'not real.' Vonnegut leaves that question open, as a good writer should. That openness is the space in which the reader is allowed to make up his or her own mind."

That Roston is attempting to foreclose some of that openness is not lost on him; but the resultant book is not the dull didactic case study it might have been. Roston provides a useful literary biography, examining Vonnegut's work and personal history. He peruses discarded drafts of the novel. He interviews the writer's family (Vonnegut's children assume their father suffered from PTSD) and friends.

Some of the best material comes by way of his conversations with other soldiers-turned-novelists like Kevin Powers and Tim O'Brien. "The Writer's Crusade " is valuable as a rumination, even if it's not a satisfying detective story.

It's not often I can locate the moment when an author first became important to me. But I can in this case. It was in the summer of 1973 when I checked "Breakfast of Champions" out of the library because of the cover, which made me think it might be a sports novel. I read it even after I figured out it wasn't. Vonnegut wandered onstage at some point and explained a lot of things to his characters, and even drew some charming pictures in the book.

It was different and I liked it, and soon I checked out all the Vonnegut novels I could find. I read them too, though when and in what order and under what circumstances I cannot recall. Memory is a funny thing; sometimes you remember things that didn't actually occur and sometimes you forget things that did. But what is real to you is what you remember, whether or not it actually happened.

I read most everything Vonnegut wrote. Maybe I missed a few magazine articles here and there. I don't remember much about some of the books, but I kept up. I liked Vonnegut because no matter how sad and bleak his worlds were, you could always tell he had a heart. He knew how bad things were and yet he had faith in people.

"The author's two-decade struggle to write a book that depicts the trauma of war truthfully, without cheapening it, anticipated the PTSD diagnosis," Roston writes. "And even more, his story of fractured identity and trips in time and space provides a navigational tool. Billy Pilgrim is a war veteran unlike any other and yet he is universal. Vonnegut circumvented conventions, labels, and false sentiments. He blew all of that up, and by doing so he put a wedge in readers' resistance to ambiguity and complexity. Vonnegut's book, and the way he lived his life, tell us an entirely original story about what it means to be human."

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com