Leyton Rainbolt had barely gotten his driver's license when he completed all the requirements allowing him to take to the skies.

Rainbolt, now 18, got his pilot's license at 17, the minimum age for a private license to fly an airplane.

For perspective, there are two 17-year-old pilots in Arkansas and 395 across the United States, according to Kiiva Williams, spokesman for the Federal Aviation Administration.

Rainbolt, a recent graduate of Central High School in Little Rock, was accepted to all three military service academies — the U.S. Naval Academy and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and the U.S. Air Force Academy.

"I knew I wanted to be an officer in the military. I knew that that was where I wanted to go. So applying to all three maximizes my chances of doing that. There are opportunities to be a pilot in any of the services, but when given my pick, I decided to go Air Force," says Rainbolt, who reported to the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., on June 23.

If all goes according to plan, Rainbolt will retire from the Air Force and become a commercial airline pilot.

A private pilot's license allows someone to share costs of flying with passengers, though charging a fare for service requires a commercial pilot's license. The minimum age for a commercial pilot certificate is 18.

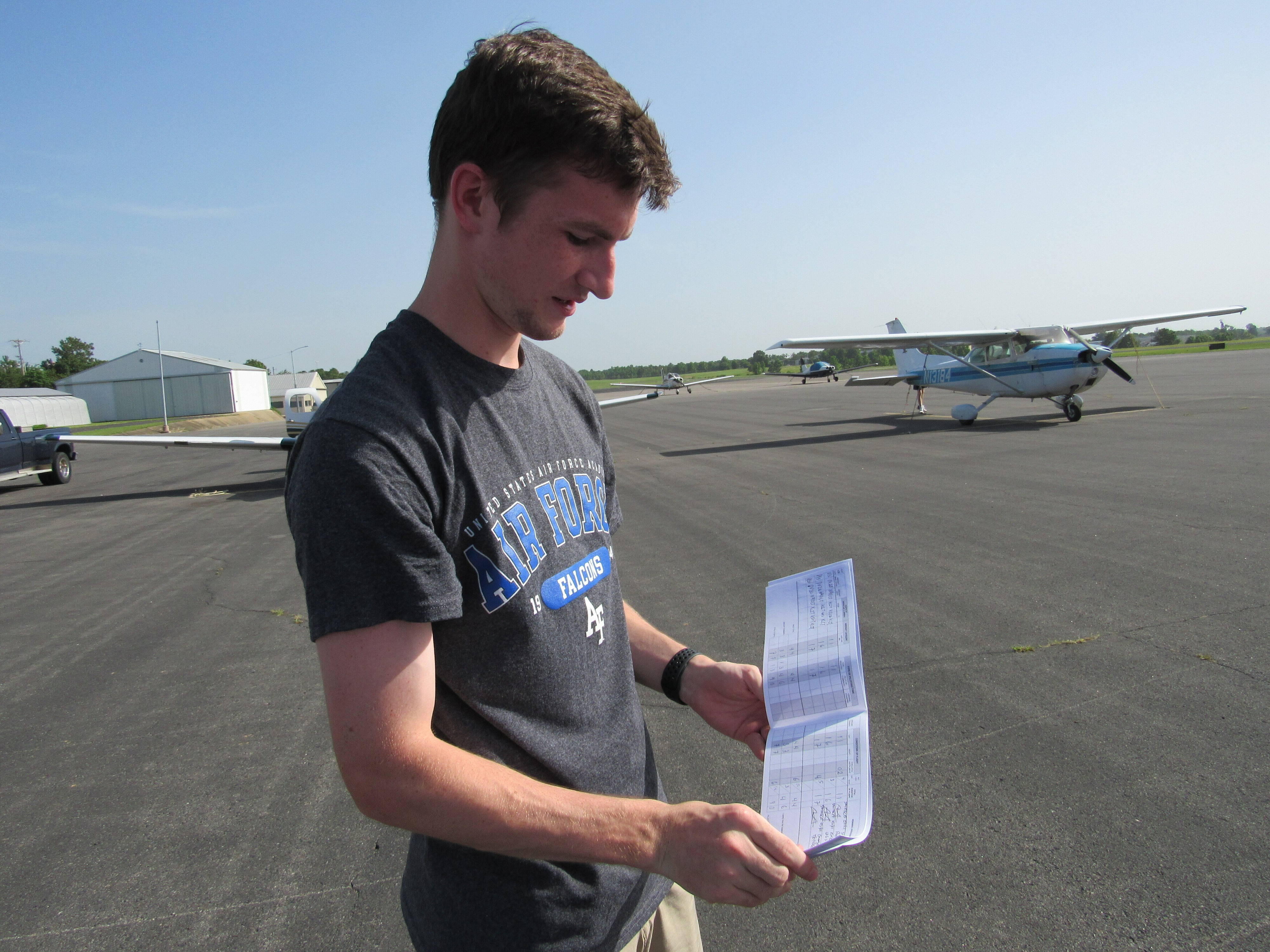

Leyton Rainbolt, 18, graduated from Little Rock Central High in May. He completed requirements last year, at the minimum age of 17, for a private pilot license. Rainbolt took one last practice flight from the North Little Rock Municipal Airport in early June before leaving Arkansas to check in at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Kimberly Dishongh)

Leyton Rainbolt, 18, graduated from Little Rock Central High in May. He completed requirements last year, at the minimum age of 17, for a private pilot license. Rainbolt took one last practice flight from the North Little Rock Municipal Airport in early June before leaving Arkansas to check in at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Kimberly Dishongh)

'JUST LOOK AROUND'

Rainbolt has trouble putting into words what he most enjoys about flying.

"It's just a gut feeling," he says. "The part of the flight I think I like the most is maybe the most mundane part, when you're just up there, everything's set and you can just look around and see everything," he says.

He has no problem, however, pinning down when he fell in love with flying.

"It was freshman year when our Air Force JROTC [Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps] unit got to do an orientation flight through Civil Air Patrol," Rainbolt says. "I was one of the cadets who got to go on that. A Civil Air Patrol pilot takes you up in one of their planes and they let you fly around a bit while you're up there, just to experience flying."

During those orientation flights, he was allowed to control the yoke (a plane's "steering wheel") and the rudder (which helps stabilize the plane), though the pilot had the ability to regain control if needed. His first flight took him around Pinnacle Mountain and up to Greers Ferry.

He was hooked.

His parents, Heather and David Rainbolt of North Little Rock, arranged for him to take a few private lessons at Central Flying Service in Little Rock. Then Central's JROTC commander told him about the Air Force Junior ROTC Flight Academy, an 8-week summer aviation training program offered through universities with flight programs around the country, a collaborative effort between the Air Force and the aerospace industry to address a nationwide pilot shortage.

Rainbolt went to the Flight Academy through the University of Central Missouri School of Aviation in Warrensburg, Mo., and before the end of the program he had completed the requirements for a license.

Devon Straw, a 17-year-old senior at Little Rock’s Central High, is learning to fly a plane through the U.S. Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps Flight Academy this summer. He’s pictured here in front of a stainless steel Peter Forster sculpture — “Pathways to the Sky” — at the James Hagedorn Aviation Complex on the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., where his course is taking place. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette)

Devon Straw, a 17-year-old senior at Little Rock’s Central High, is learning to fly a plane through the U.S. Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps Flight Academy this summer. He’s pictured here in front of a stainless steel Peter Forster sculpture — “Pathways to the Sky” — at the James Hagedorn Aviation Complex on the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., where his course is taking place. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette)

DEVON STRAW

Devon Straw, 17, a rising senior at Central, also got a scholarship to the program. He arrived at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., on June 12, to begin Flight Academy. He hopes to join Rainbolt at the Air Force Academy in 2024.

"I think it was like, seventh or eighth grade when I found out about the Air Force Academy," Straw says. "In ninth grade I joined the Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps and it was like, 'I want to go to the Air Force Academy. That's, like, what I was put on this planet to do.' I've just been working toward it ever since I heard about this program."

The training is all he had hoped for and then some.

"It's like drinking out of a firehose," Straw says. "There's a lot of different procedures and you have to memorize different checklists, and all the planes are super-modernized so they have a lot of technology in them."

Older planes have a six-pack, a dialed instrument panel that provides data about speed, altitude and more, he explains.

"These planes have a G1000, which is a really complex system. You have to know about the digital displays and all that," he says.

This part of his training will make him more prepared in some scenarios, less so in others.

"For the planes that are older and the ones that are probably cheaper to fly back home, they have six-packs so it's something I'll have to get used to if I want to fly other planes," he says.

And he does want to fly other planes.

"I'm part of the Civil Air Patrol, which is a similar organization to JROTC. They have a great cadet program that offers flight opportunities," Straw says. "Once you become a cadet pilot they actually have ways for you to get flight hours in those planes."

Straw's parents, Connie and Shane Straw of North Little Rock, have been supportive of his goals.

"He knew this was the path that he wanted to take to get where he wanted to be and so everything he does and has done since middle school has been pretty calculated and thought out and planned because of boxes he has to check to get to his ultimate goal of attending the U.S. Air Force Academy and becoming a fighter pilot, a test pilot and an astronaut," says Connie Straw, explaining that her son chose to transfer from his assigned high school in North Little Rock to Central largely because of the Junior ROTC program.

"It has kind of gotten to be where he would say, 'Here's a form, can you just sign this?' and then, 'I need a check for $20,' or whatever it is and we were signing for him to go do crazy things, but he really drove all of that and we were kind of along for the ride."

Straw jokes that she is both terrified and excited to see what her son does next, even when he calls from camp to tell her about things like stall maneuvers, requiring a student to stall the engine in flight and maneuver the plane so it doesn't spin out of control.

Her heart might stall for a minute when she hears this, she admits, but she recovers quickly.

"I think that excitement and anticipation takes over and it overrides a lot of the angst that his dad and I have about him," she says.

Straw washed planes and did some cleaning and organizing in a hangar for a certified flight instructor last year to offset the cost of some of his lessons before he was accepted to the Flight Academy.

"I think I got five flight hours in some beat-up Cessna 170, just some basic stuff, but it was enough to get me here," he says.

The whole family is grateful for the scholarship that will cover his flight instruction.

"It could run anywhere from $160 to over $200 an hour for the whole shebang," Connie Straw says. "This is something like a $26,000 scholarship to get his private pilot's license. We couldn't do that, so what a blessing."

COLIN HORNADAY

Colin Hornaday of Bryant, 19, has offset the cost of some of his flight instruction with part-time jobs saving money he made mowing lawns starting at age 12, and then when he was older from jobs at fast-food restaurants and lifeguarding at pools.

"Once I was able to become a flight instructor, when I was officially employable for aviation, I stopped doing all that and now I'm a flight instructor full time," he says.

Hornaday discovered flight simulators when he was in second grade, and in fourth grade he weighed his options.

"I was like, 'OK, I gotta figure out something to do with my life. I need to become a professional soccer player, a surgeon or a pilot,'" Hornaday says. "I went on YouTube and I watched an airline pilot video and from there I was just absolutely captivated. I spent all summer researching becoming an airline pilot."

Just before his 11th birthday, Hornaday's family arranged an introductory flight for him.

"From there, I knew what I was going to do with my life," he says.

Hornaday was just 13 when Maryland-based Piedmont Airlines flew him and his father, Steve Hornaday, to Honolulu for an event sponsored by Future and Active Pilot Advisors for middle and high school students considering careers as professional pilots. That event was held in conjunction with a regional pilot job fair.

Hornaday flew solo on his 16th birthday.

"I made it a point, after I soloed I drove my car back home by myself after it so I could say that I flew for the first time before I drove," Hornaday says.

He doesn't mind driving.

"But flying is something I'm actually passionate about. Driving is just something I have to do," he says, which is why he sometimes rents a plane from the Central Arkansas Flying Club where he's a member and flies to Arkadelphia to meet with his students at Henderson University rather than driving an hour to get there.

He got his private pilot license on his 17th birthday. He got his instrument rating, proving he could fly while referring only to instruments, between his junior and senior years of high school. He intended to get his commercial license on his 18th birthday.

"The weather messed it up, so I got my commercial pilot's license shortly after I turned 18," Hornaday says. "I got my multi-engine flight instructor certificate and then I got my instrument flight instructor certificate and I did those before I turned 19. There really aren't any other certificates I can get until I turn 21, so I'm just playing the waiting game until then, when I can become an airline transport pilot. I'm big into getting set at the minimum age, just because that's what keeps me progressing along as quickly as I can in my career."

He hopes to spend a few years as a regional airline pilot and then, by his mid-20s, to fly for a major airline.

Leyton Rainbolt, 18, got a basic flight log when he got his private pilot’s license last year and has tracked every flight, as required by the Federal Aviation Administration. “The first logbook I had [has] five pages in it,” says Rainbolt, who has since gotten a more expansive logbook. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Kimberly Dishongh)

Leyton Rainbolt, 18, got a basic flight log when he got his private pilot’s license last year and has tracked every flight, as required by the Federal Aviation Administration. “The first logbook I had [has] five pages in it,” says Rainbolt, who has since gotten a more expansive logbook. (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/Kimberly Dishongh)

CHECK-OUT FLIGHT

Rainbolt, intending to get a head start on his education at the Air Force Academy, was able to fit in one last check-out flight between graduation and reporting to the Air Force Academy.

He and his instructor, 27-year-old Hunter Medsker, flew in a four-seat, single-engine Cessna 172 from the North Little Rock Municipal Airport to Pinnacle Mountain and then rose to 3,000 feet to practice maneuvers and stalls.

"As long as you keep rudder coordination you're fine," Rainbolt explains, as much to his mother as to anyone else.

"Yes, stalls are scary," says Heather Rainbolt. "If they don't do everything right they'll go into spins. And part of getting your flight instructor license is knowing how to pull out of spins."

"That's why we do them at 3,000 feet," Leyton Rainbolt assures.

She doesn't worry much about her son, a steady, practical teenager.

"In fact, at graduation, the thing all of his instructors said was that he needed to loosen up," she laughs.

While he was in the Flight Academy last summer, she followed his path via the Life 360 app.

"I watched him fly all over Kansas and Missouri," she says. She could see that he was traveling at speeds greater than 100 miles per hour — the highest reading Life 360 affords — and she usually knew ahead of time when he was flying alone or when the engine of the plane he was flying would be intentionally cut off.

"He was the first in his program to get his license. He did it in seven weeks," she says.

She pointed out that although her son is committed to going, and though his less-than-perfect vision may prevent him from flying for the Air Force, there are several other flight training and employment opportunities, both in air and on the ground.

"Even if everyone can't be a pilot, there are still exciting roles to fill in the world of aviation, like air traffic control ..." says the FAA's Williams. He directs those who are interested to visit https://www.faa.gov/be-atc.