In the back of a limousine, Marvin Schwartz sat back and took in his surroundings. He was here, in his native New York City, for a conference in the employ of a large Arkansas-based company, the entire corporate brass of which was here with him, one very nice suit seated by the next.

As the car made its way up the Avenue of the Americas, an urban canoe parting the concrete channel along the base of Skyscraper Alley, Schwartz looked out the window.

"It's midday and I see a young guy on the street corner in a sheepskin jacket and jeans with a ponytail," he recalls of the moment. "I said to myself, 'That's me out there.'"

As a boy, Schwartz had dreamed of doing many things, all of which followed a path other than that lit by his family's vision of success by way of business and material accumulation. It was a romantic credo, one to which he ascribed early and which he would bring steadily into focus his entire life.

But right then, in that moment, the 40-something poet, journalist and simmering social radical was trapped in a luxury car with the corporate squares, a beetle in cooling agate.

"At this point, I was making a living as a commercial writer," he said. "It wasn't my first choice, but I was committed to doing this work the best way I could, making a decent salary. Then I look at this limo and I'm sitting with these guys who are all setting up their liaisons in the hotels and different things. I thought, 'I would rather be out there than in here.'"

Schwartz's purpose has frequently come to him in glimpses. Causes caught in the corner of his eye, a lone word blossoming into poetry, a single-paned glance of good to be made in the world, these he has chased and mined his entire life. Sometimes adventurous, sometimes reckless, he'd followed shadow and light from immigrant Brooklyn to the jungles of Central America, the beaches of Florida, the continent of Europe and a thousand specks on a crumpled map in between.

And at their end Arkansas -- always Arkansas -- and the wild emerald hills, gushing gurgling waters and brawny flat plains to which he would inevitably return.

"Over the years, one message seems to have resonance, this expression that when one door closes, another opens," he says. "You don't get to choose which door opens. That door opens and you walk through it because that's the right door for you to walk through at the time. If you carry the right spirit, you'll connect."

He pauses, glancing out the window. Outside is a prototypical late Arkansas springtime, the season of renewal, riotous in greenery and bloom, fulfilling the promises made in winter.

"What is the next door? I don't know and I don't know if there will be one," he says. "I have a strong community ethic. It comes from my Jewish heritage. And, it comes from working with really dedicated community people."

BROOKLYN UPBRINGING

Born in post-World War II Brooklyn, Schwartz's environment was shaped by two levers of the immigrant experience, personified by his grandfathers' common start and divergent paths within the American Dream.

"I'll tell you about my two grandfathers," he says. "David Bloom, on my mother's side, came to the U.S. in 1920 and had an entrepreneurial vision. He saw his opportunity to cultivate a market and he developed it and he became very successful.

"My father's father, Nathan Schwartz, had a worker's mentality. He went directly into the tenements and sweatshops, carried home his sewing machine, and worked for 10 cents an hour. The story is he was saving up, bit by bit, to buy his own business and then lost everything in the crash of '29. He was a wonderful man, just never accumulated wealth.

"So, I have one grandfather who could see the castle on a hill, and I had another grandfather who put the bricks in the road."

The borough in which he was raised repeated this duality of immigrant life across myriad nationalities and dialects. Some achieved what they sought; others dreamed bigger than they could reach. Schwartz, raised upper middle class, started to chafe by high school under expectations both societal and familial.

"New York City was exciting and a great place to get your street smarts and learn things, but my family epitomized the role of the immigrant, where everything about your success is judged by dollars," he said. "I found that wasn't for me."

Schwartz enrolled in Syracuse University with the intention of becoming an architect, but that idea cooled in the face of the math and science courses he'd have to take. Earning his undergraduate degree in English, he then headed for Hollins University in Roanoke, Va., for a master's degree in creative writing and literature.

Next stop Fayetteville, for his Master of Fine Arts and an intense period of personal and artistic formation. His eclectic array of classmates, professors and outside influences during this wild time was intoxicating on many levels.

"Fayetteville was a sleepy Normal Rockwell town of 15,000 people in those years, and you could get away with a lot," he says. "The creative writing students all thought we were hot s***. We were not academic program heads, that's not what we were about. We were about expression and poetry."

"There were also those among us who were Vietnam vets and while they may or may not have been talented writers, they were bringing with them a high degree of instability. Fayetteville in 1971 was pretty boring after you came back from Vietnam, so psychedelic drugs are available, hard drugs are available, guns are available. And then I had friends who were both writers and returned vets and that was a dangerous combination."

Mixing with the veterans and their demons changed some of Schwartz's views and he began to see the subtler shades of gray that added depth and shadow to the human experience.

"The height of the Vietnam War gave me a sideways view of America, where American glorification had a darker side. We saw the American military with some suspicion, we saw patriotism with some suspicion," he says. "But there is a human side to these issues and a human impact. That softened that sense of rebelliousness to understand there's a system here, there's a community that needs sacrifices, it needs builders, it needs warriors. The whole village concept means including the elderly, the poor, the infirmed, you need all of this.

"There's going to be people who are wounded along the way; there are people going to be empowered along the way. It opened my consciousness to the broadest spectrum of humanity."

ARKANSAN BY CHOICE

Poetry in the Schools gave him his first role within this village. The project sent Schwartz and some of his fellow grad students into Delta classrooms to teach their art form. He thought the experience was about giving impoverished rural kids the magic of words only to be surprised at how much he gained in return.

"It gave me an exposure to Arkansas, gave me a sense of the beauty here, a green space, a slowness of life," he said. "My immigrant heritage was all about change and don't look back. My grandparents and parents said the old world was closed, it's over, we don't talk about it. Arkansas showed me there is opportunity to put down some roots that I didn't know at that time I was looking for. So, I like to say I'm a New Yorker by birth and an Arkansan by choice."

Despite this new awakening, Schwartz was no homebody. Following his Fayetteville studies there was still a wide world out there his wanderlust hungered to experience. And besides, it wasn't like there were plum teaching gigs on every corner anyway.

"I wanted to stay in Arkansas, but there were more unemployed writers in the pool hall on Dickson Street than anywhere on the planet," he says. "When you graduated from the creative writing program in those days, this is '74, you throw your resume on the Chronicle of Higher Education and end up at a junior college in Wyoming or someplace, then you publish and work your way up. I didn't want to do that."

Instead, Schwartz set off landing teaching gigs in Guatemala, then France and later in Florida, each adventure with its own character, minor scandals and near-misses. Upon returning to The Natural State for good, he took a job with the Arkansas Democrat at the height of the Little Rock newspaper war, showing a gift for feature writing.

"I did a series called 'On The Job' and I called businesses and said let me come out, I'll give you one day of work and I'll write a story about you," he says. "I was flying with crop dusters. I was in the pilot house of riverboats. I was with log crews out in the Ozark National Forest. I threw pizza one morning with Gio Bruno, I spent a morning with a baker at 4 a.m. Then, I'd write it up and it would be the Sunday feature. It was fun, and I got to know Arkansas even more."

Schwartz liked everything about that job but the money, and after being turned down for a raise, he left for a string of nondescript gigs. What got him through the self-described dark period was freelance writing on the side, working on his poems and rediscovering competitive swimming, a sport he'd taken up as a teenager. Through competition he made connections that led to a budding technical company called Acxiom.

"They said, 'We've got dozens of openings. The company is exploding with growth,'" Schwartz remembers. "I knew nothing about computers. All my writing was on manual typewriters."

TAKING ON NONPROFITS

At Acxiom, he made more connections which was fortuitous given corporate jobs are made to be one day eliminated, as his eventually was. Thanks to networking skills, Schwartz landed a string of positions with nonprofits that finally allowed his soul and his skill set to shake hands.

Two roles stand out on the personal satisfaction scale, including Arkansas Land and Farm Development Corporation, dedicated to preserving land ownership among Black family farmers. Schwartz not only beat the drum for financial contributions, he helped create a national youth program that still exists 30 years later. YEA, Youth Enterprise in Agriculture, educates youths at sites in Mississippi, Chicago and Arkansas where they get a firsthand look at various segments of the ag industry.

"We rotate these kids where they work on a farm living with a mentor family in Arkansas," he says. "Then they go to Piney Woods School [in Mississippi] to get high-quality prep education. Then they go to Chicago High School and visit the Board of Trade and General Mills and learn the corporate side of things. And we created this all from scratch."

The second notable work came with Heifer International. Schwartz spearheaded a program to help resuscitate local farm economies in Romania, setting up processing and distribution of foodstuffs while diverting surpluses to the country's brimming orphanages. Heralded by the United Nations, the program also improved education and skills training to help orphans support themselves in adulthood.

"Marvin has an ability to understand work related to human development. He has a keen interest in that," says Andre Stephens, executive director of the St. Francis County Assisted Living Community in Forrest City and an ALFDC co-worker. "He has an eclectic set of skills gained through a diverse range of topics and experiences he himself has had.

"Marvin helped me hone my oral and written communication skills and more importantly, how to scan other people and be comfortable in an environment that may be uniquely different from my own."

As if that weren't enough, Schwartz has written steadily. To date, he has authored two volumes of award-winning poetry and nine books ranging from the history of VISTA, a domestic version of the Peace Corps; biographies of corporate scions J.B. Hunt and Don Tyson; and cultural works focusing on Central High School and rockabilly pioneer Sonny Burgess. His latest, the memoir "True Stories," was published in 2018.

DIVING IN

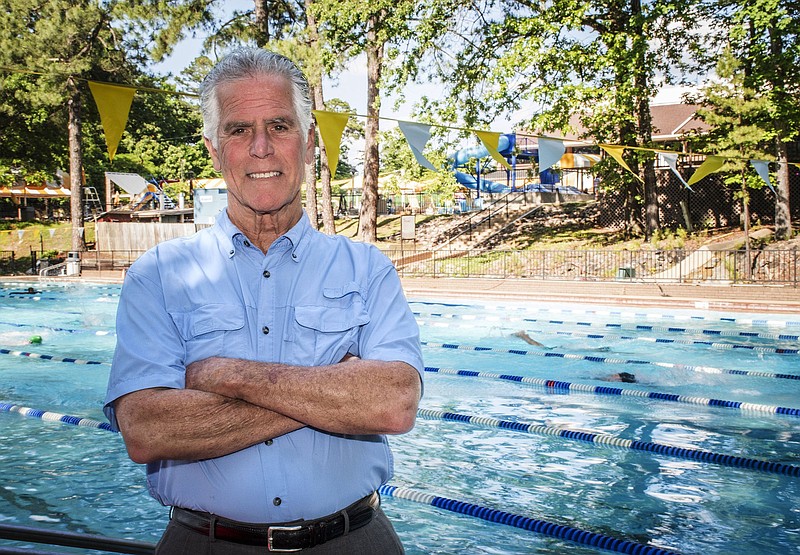

These days, Schwartz has settled into the retired life, though not in all things. He still swims competitively, relishing the discipline of a sport that has crowned him U.S. Masters Swimming national champion eight times and seen him inducted into the Arkansas Swimming Hall of Fame. His athletic career is a calling card for which he is known across the state and around the country.

"He has been ranked in the top 10 in different events on 85 different occasions and even that probably understates his achievements," said Trip Strauss, a friend and fellow swimmer. "There's a group of us friends who swim together and no one has been doing it as long as Marvin. We all look up to him because he has those great accomplishments.

"More than that, he's a great person, a Renaissance man who really has empathy toward his fellow man. He's an outstanding human being."

Another activity that continues to command Schwartz's attention is the Ozark Society Foundation of which he is chairman. The fundraising arm of the Ozark Society, it deals in conservation efforts concerning Arkansas' woods, water and trails. Of late, he has been active in the 50th anniversary of the Buffalo National River, notably in the production of a film, "First River, How Arkansas Saved a National Treasure."

"We produced this film to make people aware of their responsibilities," he says. "The beautiful river we have today, we have this treasure because of the vigilance of people who came before us. The film honors those people and raises awareness of the necessity of vigilance and exercising one's civic responsibilities. It's what you're supposed to do."

At this, he leans back in his chair, once again glancing out the window. He still spots castles on the hill, and when he does, calculates the bricks required to pave a way for himself and others to reach it.

"I feel pretty empowered right now. I'm in good shape for a person my age. Still got most of my marbles. We'll see what comes next," he says. "I know there's always opportunities and as long as I'm able to respond, I'll do what I can. There's been an influence to go into politics, but that's not for me. I'm too blunt.

"There's a Jewish expression, tikkun olam; it's Hebrew meaning 'repair the world.' The world we live in is flawed. It's not perfect. Your role is to repair it and you have been given, through some divine gift, resources. Every one of us has our own set of resources and that's the whole village concept again. Some are more robust. Some are quieter. Some are in words. Some are in music. Some are in just being a compassionate listener."