Death hasn't erased the testimonies left behind by a number of Black Arkansas Christians, people of faith who endured slavery at the dawn of their lives and the Great Depression at life's twilight.

Addressing a symposium, remotely, on "African Americans and Religion in Arkansas," Lane College President Logan Hampton shared some of their stories, yielding much of his time so that they could have the floor.

Among others, he quoted Aunt Adeline of Fayetteville, who recalled playing church as a child and Lucretia Alexander of Little Rock, who shared memories of pre-emancipation Sundays in the South.

"Faith and church were regular parts of life for our ... ancestors,'' Hampton said.

By sharing eye-witness accounts, Hampton said, "I am attempting to limit my voice and to amplify the voices of those who had firsthand experiences. They have some wonderful stories to tell."

If it had not been for the Great Depression, these Arkansans' stories likely would have gone to the grave with them.

A New Deal agency, launched during the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, helped bring the project to fruition.

The Works Progress Administration, which provided employment for millions of Americans during the crisis, paid people to interview formerly enslaved people.

Approximately 2,300 Black people, most of them still living in the South, agreed to share their stories.

In her interview, Aunt Adeline, who lived for a time along the stage coach route in Northwest Arkansas, recalled a spartan childhood.

"We didn't have many toys; maybe a doll made of a corn cob, with a dress made from scraps and a head made from a roll of scraps. We were playing church. Miss Fannie was the preacher and I was the audience. We were singing 'Jesus, My All, to Heaven Is Gone.' When we were half way through with our song we discovered that the passengers from the stage coach had stopped to listen. We were so frightened at our audience that we both ran. But we were coaxed to come back for a dime and sing our song over," she recalled.

The interviews sometimes portrayed religion as a two-edged sword.

In Alexander's recounting, Christianity could be a tool of white oppression in daylight hours but a fount of Black liberation after dark.

On the farm where she lived, the Christian Sabbath was not a day of rest for Black people, she recalled.

"They would make the slaves work till twelve o'clock on Sunday, and then they would let them go to church," she said.

Not given time to clean up after a hard morning's work, they would show up "sweaty and smelly" and get scolded for it, she recalled.

They also weren't allowed to worship with their enslaver.

"The n***** didn't go to the church building; the preacher came and preached to them in their quarters. He'd just say, 'Serve your masters. Don't steal your master's turkey. Don't steal your master's chickens. Don't steal your master's hawgs. Don't steal your master's meat. Do whatsoever your master tells you to do.' Same old thing all the time," she recalled.

Later, out of the prying eyes of the enslavers, Black people would share their own version of the Gospel.

"My father would have church in dwelling houses and they had to whisper. ... Sometimes they would have church at his house," she recalled. "That would be when they would want a real meetin' with some real preachin'. It would have to be durin' the week nights," she recalled.

The services were ecumenical.

"You couldn't tell the difference between Baptists and Methodists then. They was all Christians," she said, adding, "I never saw them turn nobody down at the Communion. ... They used to sing their songs in a whisper and pray in a whisper. That was a prayer-meeting from house to house once or twice -- once or twice a week," she said.

Blessed with a long life, Alexander said, "I took care of myself when I was young and tried to do right. The Lord has helped me too."

"If you want to beat the devil, you got to do right. God's got to be in the plan," she said.

Hampton's presentation, titled "Faith of Our Foreparents," underscored the resiliency of the Black community and its churches as well as the role faith has played through the years.

While Hampton only had time to offer excerpts, the full accounts are available on the Library of Congress' website. The collection has been dubbed: "Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1938." See tinyurl.com/2p9xv79b.

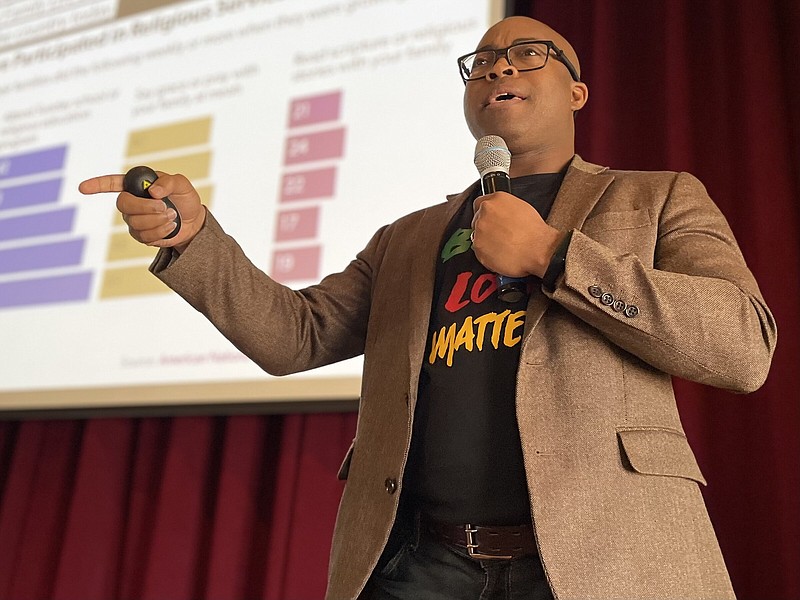

More than 60 people attended the symposium, which also included a session featuring Edna Mack-Pettigrew, an associate minister at Bethel AME Church, titled "I Am A Woman, I Am A Minister" and a session on "Religion from a Millennial's Perspective" by Black History Commission of Arkansas commissioner Walter Washington.

Mack-Pettigrew said women in ministry is not "a 20th century phenomenon," noting women who blazed new trails in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Washington said younger generations aren't interested in sitting through a "one-way conversation" about religion.

"They're looking for the opportunity to engage with one another as believers, so they know they're in this together," he said.

The event was sponsored by The Black History Commission of Arkansas, in collaboration with the Arkansas State Archives.