I have been re-organizing my record collection.

I remember when things existed in the actual, when a record was something you could touch (and smudge and damage), and understand that those sensations allow some of us comfort.

Album covers and liner notes and all the tactile sensations that went along with taking a record from its sleeve and setting it on a turntable and watching it spin and setting down a stylus on its surface just so — there is something in the dig of the needle, the variable wow and flutter of each turntable, the imprecision of the mechanical that foments our nostalgia.

It's not like that anymore. Except for a few token CDs and vinyl albums, my entire music collection resides on a hard drive. "Re-organizing" means mostly cleaning up the metadata in the digital files, an extended adventure in OCD behavior.

I scroll through my collection looking for misspellings, duplicate files and other glitches. When I started digitizing CDs (and some LPs and cassettes) onto computer peripherals 25 years ago, I started out painstakingly recording the artists by last name first. Later, when Gracenote's Music ID software came online to automatically identify CD metadata, it populated the information with first name first. I fought this for a while, painstakingly formatting each CD I ripped to the last-name-first convention.

About 10 years ago, I gave in and decided that Gracenote's convention made as much sense as mine, given that a lot of artists didn't perform as conventionally named entities anyway. I never typed in an artist's name as "Loaf, Meat" or "Bastard, Dirty Ol'" but came to understand that you browse a digital collection differently from the way you do an analog one.

WALLS OF VINYL

When I had walls of vinyl, I used the method made famous by Daniel Stern as Shrevie in Barry Levinson's 1982 movie "Diner." I arranged them alphabetically by last name and band name. I arranged records by the same artist in chronological order. (I differed from Shrevie's system in that I didn't segregate by genre — R&B, Blues, Jazz and Folk were co-mingled with the Rock titles — but I isolated the classical albums, which were organized by composer.)

This meant it was easy to find any particular album by any particular artist — you could run your fingers over the spines until you came to it. And there was only one right place to refile the album.

At the height of my record accumulating days — I wouldn't call it collecting, it wasn't as intentional as that — I had slightly more than 5,000 albums. They took up a lot of space, more than I'd be willing to give them these days. (An old friend, John Andrew Prime, who was chief music critic for the Shreveport Times for a couple of decades, once told me he blamed his record collection for cracking the foundation of his house. I can see how that happened.)

These days iTunes (I still use iTunes) tells me my collection consists of 152,260 tracks from 16,416 albums that take up 1.76 terabytes of space on a four-terabyte hard drive. This is, iTunes assures me, 416.4 days of music.

That album number is inflated because of the way iTunes counts albums. If I have a single song from an album, iTunes credits me with having that album. Sometimes compilation albums are double and triple-counted.

Part of what I'm doing when re-organizing my collection is reconciling these partial albums — changing the metadata so that the system understands that "People Take Warning! (Murder Ballads & Disaster Songs, 1913-1938)" is a compilation record featuring various blues and folks artists that was originally released on three CDs, not three — or a dozen — different albums.

Why? Because that's the sort of man I am.

I understand it really doesn't matter. Subscribe to any streaming service and you'll have access to a lot more music than I have in my library. While I have some things you won't easily find on Apple Music, Amazon Music or Spotify, convenience usually leads me to use a streaming service when I want to play a song, album or playlist for someone else.

Music library-tending in this digital age: If you’re looking for, say, “Waterloo Sunset” by the Kinks, type the title into the search window, hit return and up will come the version you’re seeking … and then some.

Music library-tending in this digital age: If you’re looking for, say, “Waterloo Sunset” by the Kinks, type the title into the search window, hit return and up will come the version you’re seeking … and then some.

NO HUNTING REQUIRED

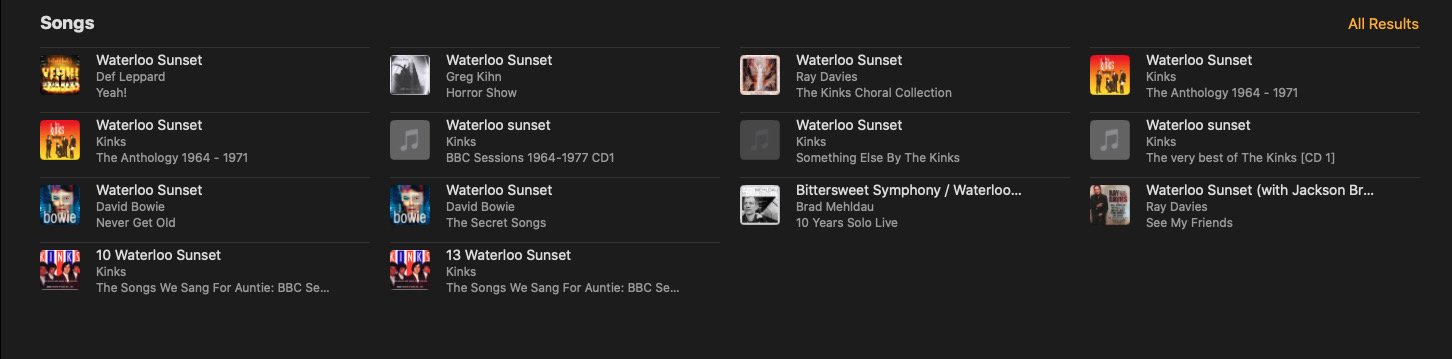

Now, if I'm looking for a particular piece of music, I type the name of the artist or the album (or a song on that album) into a little box, and it pops up in a window. There's no real browsing, and no serendipitous rediscovery of an album I forgot I owned, but if I'm looking for "Waterloo Sunset" by the Kinks, I type the title into the search window, hit return and — lo and behold — I get 14 results: the recording I'm looking for — the 1967 single that they included on their "Something Else" album — plus cover versions by Def Leppard, David Bowie, Greg Kihn and the jazz pianist Brad Mehldau.

There is a live version the band recorded for the BBC and three different versions performed by Kinks frontman-turned-solo artist Ray Davies: one solo guitar rendition, a duet with Jackson Browne, and a version Davies recorded with the Kinks Choral Collective.

The other copies of the song are presumably the same track as the original single from various anthologies released over the years. Were I worried about space on the hard drive, I might delete these duplicates, but I figure that if the music I've collected for more than 50 years takes up less than half of the hard drive dedicated to it, I'm probably all right with storage space for a while.

But — and this bothers me far more than it ought to — I'm missing the 1997 cover of "Waterloo Sunset" by Cathy Dennis, a British pop star who recorded the song with Davies' blessing (he appeared as a cab driver in the inevitable video).

Dennis — who might be better known as co-writer of Katy Perry's "I Kissed a Girl," Kylie Minogue's "Can't Get You Out of My Head" and Britney Spears' song "Toxic" — did a good job with the song, but I've never felt the need to seek it out until now that I realize that it has disappeared off the hard drive.

Why do files do this? No one has ever given a good answer, but a certain percentage of music files evaporate every year, which is why hard drives aren't considered the best for archival purposes. If you really need something to be here in the year 2050, you probably should burn it onto a CD or DVD and store it properly.

BACK THAT SONG UP

Luckily, I have another four-terabyte hard drive onto which I periodically back up the contents of the music drive. So I can go on there, search and find the Cathy Dennis track that's missing and move it painlessly back on the music drive (along with the rest of Dennis' album "Am I the Kinda Girl?" which had also mysteriously dropped off the hard drive. So update that to 152,271 tracks).

This doesn't always work; sometimes I search for something and find it missing from the back-up drive too. I distinctly remember receiving re-issues of John Denver's early '70s albums from the record company a few years ago, and dutifully ripping them onto my drive. But they're gone. Gone from the back-up drive as well.

All I'm left with is a copy of "The Essential John Denver" and the Denver tribute record "The Music Is You," which includes My Morning Jacket's fantastic cover of "Leavin' On a Jet Plane" and Lucinda Williams' cover of "This Old Guitar."

I can roam through my digital library like Hannibal Lecter through his memory palace — remembering and rediscovering things purposefully placed there. I can sort by any number or variables, by artist, by release date, by the number of times I have played a track. These days I often find it useful to sort by date added, which reminds me of another friend who arranges his records by the order in which they were bought. His shelves reflect his evolving tastes and interests; there is a visual representation of his musical journey.

And, as with actual memory, there's no way to tell exactly what we've lost that we don't miss. Pop music is at its best ephemeral; the unreproducible kick of a garage band's accidental chord. Maybe the best song is the one you heard only once on a summer night in 1985. You didn't catch the title or the artist, but you'll always remember the bass line.

A friend of mine swears he remembers a Leonard Nimoy cover of David Bowie's "Space Oddity." He heard it for sure, one night in the early '70s, on a Chicago radio station bouncing off the ionosphere.

This sounds plausible. In 1972, Pickwick/33 Records, a bargain label that specialized in re-issuing Capitol Records' unused back catalog, took various recordings Nimoy had made over the years and issued them as as an album called "Space Odyssey," an obvious and probably intentionally confusing reference to the then-popular Bowie song.

At the time, Nimoy had entered the pop culture pantheon as Mr. Spock, the uber-rational second in command of the Starship Enterprise on "Star Trek," a show that enjoyed a renaissance through reruns in 1972, and was more popular then than when it was running in prime time.

While Nimoy covered some space adjacent songs (and "The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins"), he didn't touch the Bowie song. (William Shatner would record a spoken-word version of the song, but not until 2011.) I've looked. It doesn't exist.

MANDELA EFFECT

There is a phenomenon called "the Mandela Effect," where some number of people share specific false memories. Like they remember the children's book series about the Berenstain Bears being about the Berenstein Bears, or hearing the news in the 1980s that Nelson Mandela had died in prison. (He died in 2013, after being released from prison and serving as president of South Africa.)

There are psychological explanations for why these false memories persist, and I'm not sure there's anything more interesting to it than the obvious fact people often don't pay attention as well as they should and get things mixed up.

But if you can look into the idea of the Mandela Effect, you will learn that people have all kinds of theories about why it occurs. Some people think there are occasional glitches in the time-space continuum that cause us to unknowingly leap from one reality to a slightly altered one.

So maybe Leonard Nimoy did record "Space Oddity," and it somehow got deleted when our current timeline split off. Maybe it's out there, like the truth, on some cosmic back-up drive.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com