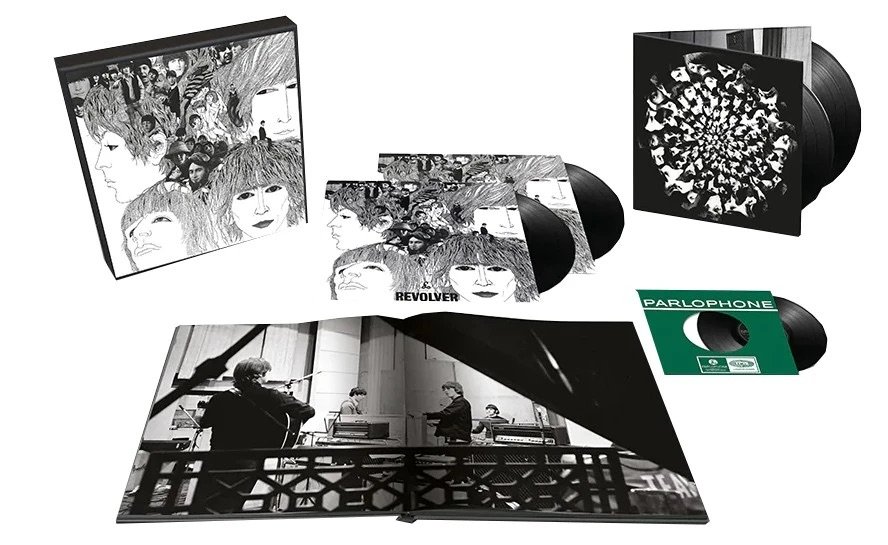

If you are the sort of person who reads newspaper essays about record albums released in the 1960s, you might already be aware of the newly mixed and expanded special-edition packages of the Beatles' "Revolver" released late last month by Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UMe.

As per usual, there are different iterations of the re-release, including a four-vinyl record LP edition that lists for about $250, a five-CD package that lists for about $150 and a "Special Deluxe" ("budget") two-CD, 29-track edition you can pick up for about $25. If, like me, you are satisfied with just the 63 tracks released in the more upscale version of the boxed set, you can stream them on most digital subscription platforms.

And you probably should because, though I think "Revolver" is a tad overrated, the Beatles' revolution really began a year earlier, with 1965's "Rubber Soul." But I've heard that the vaults aren't as rich with material surrounding that project, so maybe the invariable boxed set won't be quite so enlightening when it eventually appears. "Revolver" is unquestionably one of the landmark albums of the '60s and might be the Beatles' best and most important work.

Think about this: Taylor Swift is 32 years old. And while I will no doubt incur the wrath of many of her true believers by saying this, for all the virtues of her songwriting, her work remains jejune and boy-centric. It's what you'd expect; she's a pop singer. It's not her fault she's not Joni Mitchell.

When "Revolver" was released in August 1966, Ringo Starr was one month past his 26th birthday. John Lennon was 25. Paul McCartney was 24. George Harrison was 23.

They were a boy band.

TURN THE PAGE

The week after "Revolver" was released, the Beatles mounted their third and final concert tour of North America. They played 18 shows in 17 days, mostly in large open-air stadiums. It was not a satisfying experience for the band; Harrison and Lennon were especially frustrated. Lennon even took to screaming obscenities at the crowd during performances — no one could hear anything anyway.

Part of the problem was the backlash associated with a March 4, 1966, London's Evening Standard interview with Lennon that included the singer musing that "Christianity will go. It will shrink and vanish. We're more popular than Jesus now."

Although in context Lennon's remark seems more an expression of disbelief than an advertisement of the band, by the time the band arrived in America, Beatles merchandise was being heaped onto bonfires and burned. Not even Lennon's public apology could prevent the tour from being a commercial as well as artistic disaster.

About half the seats available on the tour went unsold, and after the band's last concert in San Francisco's Candlestick Park, Harrison abruptly announced that he was leaving the band. For a time it looked as though the Beatles might dissolve.

But Harrison was coaxed back, and a plan that had been kicked about even before the band undertook its final tour was put in place. They had become too big a phenomenon to continue playing rock 'n' roll in any traditional sense; they had not only outgrown their audience, but their concerts had degenerated into parody. The only alternative to breaking up was to retire as a touring band. They were no longer entertainers; they were artists working with sound, in the studio. "Rubber Soul" and "Revolver" had shown them the way.

They essentially shed their old "yeah-yeah-yeah" pop style for a more mature Bob Dylan-influenced musical identity. No longer were they creations of the record company. Their music had more to do with expressing ideas than selling units. This was a leap Frank Sinatra never made; that Elvis Presley never contemplated.

Dylan was in the process of making pop music a serious endeavor worthy of adult enterprise, but he was coming from a more academic direction, that of the self-serious tradition of the American folk singer, with its leftist Woody Guthrie/Pete Seeger/"Sing Out!" wing issuing political broadsides in 4/4 time. (To his credit, Dylan was transcending that sort of overt messaging at about the same time the Beatles were dabbling in musique concrete and Indian raga drone rock.)

And while the maturing of a pop star into a would-be philosopher king (see West, Kanye) is a cliche now, the Beatles really went for it with "Revolver," which, in retrospect, is a more satisfying and cohesive work than anything that came afterward, though as someone who has written extensively on "Sgt. Pepper," "The Beatles," "Let It Be" and "Abbey Road," I understand that part of the pleasure of listening to "Revolver" is simple rediscovery.

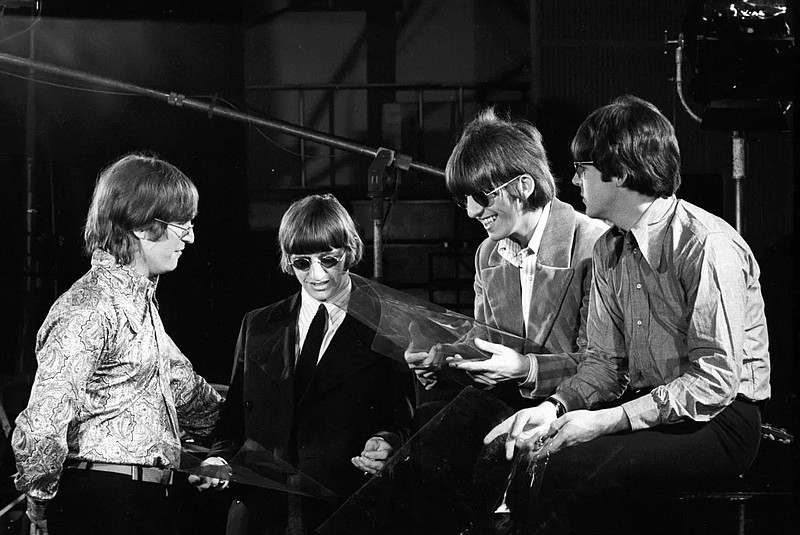

These products are representative of the newly mixed and expanded special-edition packages of the Beatles’ “Revolver.”

These products are representative of the newly mixed and expanded special-edition packages of the Beatles’ “Revolver.”

'REVOLVER' SLOW TO SPIN

"Revolver" was not always seen as one of the most important albums in the Beatles' oeuvre. If you go back to the 1983 edition of "The New Rolling Stone Record Guide," which served as a kind of Bible for pop music writers well into the '90s, you'll notice that "Revolver" gets pretty short shrift in the Beatles entry.

Co-editor John Swenson, who wrote the Beatles' entry, does award the album five stars — "Indispensable: a record that must be included in any comprehensive collection" — but in the rather long essay that follows the ratings (14 other Beatles albums are also awarded five stars; nine more get four stars) "Revolver" isn't mentioned by name, but is conflated (possibly by an editing error) with the U.S.-only 1966 release "Yesterday... And Today," one of those albums that Capitol compiled from tracks that had been left off the U.S. editions of Beatles' albums.

And I remember regarding "Revolver" as a decent Beatles album, but hardly, as the ad copy has it, the "album that changed everything."

"Spinning popular music off its axis and ushering in a vibrant new era of experimental, avant-garde sonic psychedelia," the puffery continues, "'Revolver' brought about a cultural sea change and marked an important turn in The Beatles' own creative evolution."

I don't think that's wrong. But, like most people, I'm not quite old enough to have experienced the Beatles as a fresh phenomenon. I started buying their records with my own money when "Let It Be" came out in 1970 — I was given a copy of "Sgt. Pepper's" soon after its release — and backfilled my Beatles collection while I was in high school, largely ignoring their early period in favor of the later "more sophisticated" (to my young mind) stuff. There was a time when I thought "Revolver" preceded "Rubber Soul," probably because I acquired a copy of "Revolver" before "Rubber Soul."

But I do remember cringing at "Taxman," the whiny George Harrison complaint that leads off "Revolver." I didn't like it when I first heard it (on the radio). I still don't like the song but understand its significance as the Beatles' first topical song (though it's exactly the sort of finger-pointing "journalism" that Dylan was moving away from with his 1966 album "Blonde on Blonde") and McCartney's (not Harrison's) Indian-inspired guitar solo is one of the best guitar parts he ever contributed to a Beatles' track. (And strong evidence for those who insist McCartney was the best lead guitarist in the band.)

MEET CUTE

But though "Taxman" was the leadoff track — the first time a Harrison composition had been so featured — the first revelation of "Revolver" is the second track, McCartney's "Eleanor Rigby," the first time McCartney's lyrics departed from conventional romantic narrative.

No Beatles played on the track — Martin arranged it for a string octet accompanying one of McCartney's best vocals, padded by Lennon and Harrison's backing lines. There's an audacity to following "Taxman" with "Eleanor Rigby"; both of these ominous songs map different sources of misery, though the contrast seems to point up the relatively trivial nature of Harrison's protest. (Harrison would eventually realize the problem with "Taxman" himself, but, again, he was only 23.)

It's tempting to see Lennon's "I'm Only Sleeping" as John being John, lazy and drug-wrapped and tricked up with varispeeding, which gives the vocal (Lennon famously never liked the sound of his natural voice) a distant somnolent quality.

Harrison's second track on the album (he got three on "Revolver," the first time he was allowed more than one song per album side), "Love You To" is more interesting than "Taxman," and probably his first attempt at writing a Beatles' song completely by himself. (Lennon helped out with the lyrics for "Taxman," but he doesn't appear on this track while Starr and McCartney's contributions are minimal.)

"Here, There and Everywhere" is reportedly McCartney's answer to "God Only Knows," which was released in the summer of 1966, as the Beatles were wrapping up the "Revolver" sessions. (Wilson has said he was inspired to write "God Only Knows" and much of the "Pet Sounds" albums by listening to "Rubber Soul.") It's a pretty McCartney ballad, inspired by the singer's romance with Jane Asher, tinkered with in the studio to excite the vocals a little bit.

"Yellow Submarine" was the obligatory Ringo-sung track put together by Lennon and McCartney working more or less together (the Scottish singer Donovan is said to have assisted with the lyrics). It's one of those ear-wormy bad Beatles songs that most of us needn't ever hear again, though it sounds like it was fun to record.

It's followed, almost perversely, by Lennon's ferociously insistent guitar introduction to "She Said She Said," a track that was reportedly inspired by a trippy conversation Lennon and Harrison had with Peter Fonda about what it feels like to be dead while they were all under the influence of LSD. McCartney reportedly stomped out of the recording session and Harrison may have played bass; no one really remembers.

Side two opens with "Good Day Sunshine," a McCartney song that feels like a precursor to the "granny music" Lennon hated so. The song feels like an orange juice commercial, and while I appreciate the filigree of George Martin mock ragtime piano playing and the vocal harmonies that seem to angle in from all sides like magicians' swords sliding into the box constraining his assistant ... uh, hard pass.

Better is "And Your Bird Can Sing," which Lennon always diminished as a throwaway. The double lead guitars (Harrison and McCartney) are very cool (though I like a jangly early version, recorded with Byrds-style Rickenbackers, better than the official album release). What's clear here is that Lennon is putting someone down, whether it's Frank Sinatra or Mick Jagger or his band mate McCartney. It's not the "Positively Fourth Street" Lennon probably wanted it to be, but it is nasty, and a nice riposte to "Good Day Sunshine."

"For No One" is McCartney going his own way again, foreshadowing the Beatles' later work where the other members of the band basically worked as sidemen to the writer of whatever song they were working on. So McCartney plays piano, bass and clavichord, with Starr on drums and percussion. The principal French horn player for the Philharmonic Orchestra, Alan Civil, improvised his overdubbed part. The lyric is poignant and personal and predicts the end of his affair with Asher ("a love that should have lasted years"). It's really a lovely piece.

"Doctor Robert" is mostly Lennon, and mostly straight-ahead rock about a amphetamine-injecting Dr. Feelgood. One of the few Beatles songs that can arguably be called underrated and under-played. That's followed by Harrison's earnest "I Want to Tell You," which is his strongest song on the album, an emotive but restrained plea for more direct and meaningful conversation, between artist and audience as well as between lovers.

Then McCartney's Tamla/MoTown extravaganza "Got to Get You Into My Life" blows the doors off the record. While it's sort of a Stevie Wonder pastiche, the bounce and flow of the horn section is infectious. McCartney's enthusiasm is similarly energizing — and then you come to understand that the singer is not talking about a new potential lover but marijuana.

TOMORROW NEVER KNOWS

Finally, the track that wraps up the album is drone raga "Tomorrow Never Knows," which is primarily a Lennon track — though McCartney shares writing credit and Harrison's influence is felt in the Indian modal backing track, which features sitar, tambura and electric bass guitar. The Beatles went from writing about love at first sight — "I've Just Seen a Face," presented by McCartney to the band in June 1965 — to writing about ego death in about six months.

Which speaks to the larger importance of "Revolver"; it's best seen as one of the first of an extraordinary number of what might be called progressive rock 'n' roll albums released in the late '60s. Dylan's "Blonde on Blonde," The Who's "A Quick One," The Byrds' "Fifth Dimension," The Beach Boys' "Pet Sounds" and Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention's "Freak Out" all sought to extend the frontiers of the rock album and all seemed to be in conversation with one another.

None of them would ever be cute again.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com