It's a Friday afternoon earlier this month and LaToya Hobbs is at her Baltimore home helping one of her two sons with his math homework. When asked how things are going she replies, somewhat unconvincingly: "Uh, they're good."

Hobbs, a native of Little Rock and graduate of North Little Rock High School, may be more at ease with her artwork than wrestling with double-digit division. Recent pieces by the 39-year-old printmaker have gotten some high-profile attention.

Her 2019 woodcut, "Mrs. Burroughs," is included in "The Power of Portraiture: Selections from the Department of Drawings and Prints," a new exhibit that runs through Feb. 7 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. With more than 60 works from the 17th century through the present, the show includes heavy hitters like Francisco de Goya, Elizabeth Catlett, Eugene Delacroix, Pierre Bonnard, Willie Cole and others.

"Mrs. Burroughs" depicts Margaret Taylor Burroughs, an educator who founded the DuSable Black History Museum in Chicago. She was also a writer and visual artist, known best for her linocuts. Hobbs' portrait was inspired by Burroughs' 1956 print "Mother Africa."

Hobbs, who is married to fellow artist and Pine Bluff native Ariston Jacks, was first exposed to Burroughs' art while earning her master's degree in printmaking at Purdue University, where she worked part time at the school's Black Cultural Center.

"I was put in charge of cataloguing the works in their collection, and I came across some works by Margaret Burroughs and the print, 'Mother Africa.' What struck me about it was this stippling effect that she used to create the portrait of the figure in that work, and in my later work I started experimenting with that."

Artist LaToya Hobbs, a native of Little Rock who now lives in Baltimore, creates woodcuts and prints of Black figures. Her work is being shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and will be featured at the inaugural exhibit at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Art in April. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette/Mike Jon)

Artist LaToya Hobbs, a native of Little Rock who now lives in Baltimore, creates woodcuts and prints of Black figures. Her work is being shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and will be featured at the inaugural exhibit at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Art in April. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette/Mike Jon)

Hobbs is a professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore and is a founding member of Black Women of Print, a nonprofit whose aim is to promote the stories and history of Black female printmakers. "Mrs. Burroughs" was part of "Contiuum," the inaugural portfolio created in 2020 by members of the group that pays homage to Black female artists and influences like Burroughs, Catlett and Emma Amos.

The portfolio is now part of the Met's collection and its images are at the heart of "The Power of Portraiture," according to the exhibit's page at metmuseum.org.

"Their prints, along with those by Lorna Simpson, Charles White, Fred Wilson and John Wilson, reveal the expressive potential of portraiture," the page reveals. "By depicting both anonymous sitters and well-known figures such as Malcolm X, Lena Horne and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., these artists call attention to the relationship of representation and power."

Hobbs visited the Met late last month to see the exhibit.

"I felt honored and really blessed to see my work [with that of] so many other wonderful and historical figures within the medium of printmaking," she says. "It was a great experience."

“Mrs. Burroughs,” 2019, Woodcut by LaToya Hobbs, is featured in “The Power of Portraiture: Selections from the Department of Drawings and Prints” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette/from the collection of the Met)

“Mrs. Burroughs,” 2019, Woodcut by LaToya Hobbs, is featured in “The Power of Portraiture: Selections from the Department of Drawings and Prints” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette/from the collection of the Met)

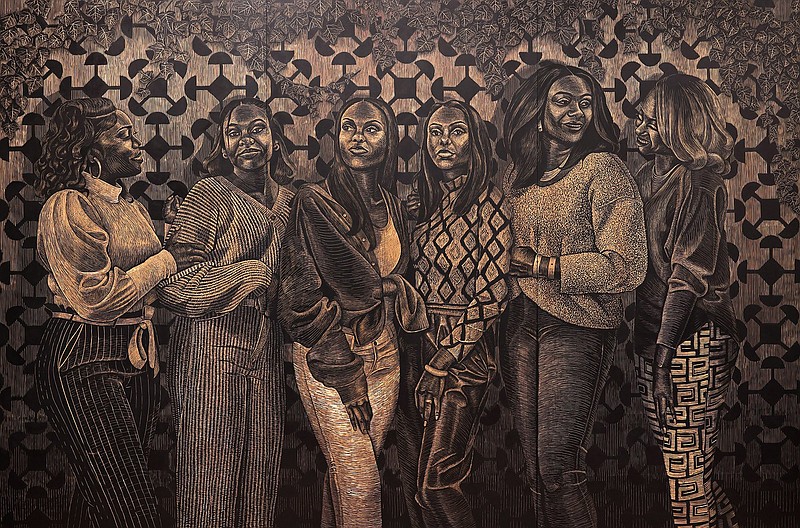

Late October was also when the International Fine Print Dealer's Association's Fine Art Print Fair took place at the Javits Center in New York. It was there that Hobbs debuted "Genette's Daughters," her ambitious, 8-by-12-foot relief woodcut carving that was commissioned for the fair with support from the association. She also showed a collection of prints she made of her fellow Black Women of Printmaking members at the fair.

"Genette's Daughters" depicts a group of six sisters whose parents, Dexter and Genette Howard, were pastors at a church Hobbs attended in Fayetteville. Hobbs made the piece after seeing a photo of the sisters posted online by the Howards.

"The last time I saw them, they were little kids," she says. "Seeing the image of them as adults was a very nostalgic experience for me and played into some of the themes I was already exploring. This kind of looks at the legacy of Pastor Genette and the role she played in my life when I attended their church and how that has expanded to her children."

To create it, Hobbs first drew the image in white pencil onto a cherry wood panel painted black. She then painstakingly carved it into the panel.

"I'm taking what would be considered the matrix (the woodblock) and presenting that as the final artwork," she says in an email. "I'm taking the element I love most about my printmaking practice (the carving process) and putting it on display."

"'Genette's Daughters' kind of turns the print world on its head by revealing not the print but the matrix as the art object," said Jenny Gibbs, executive director of the print dealer's association, in a profile of Hobbs at 1stdibs.com.

Says Hobbs: "I still do traditional printmaking where I am carving a block for the purpose of producing an edition of works on paper, but I also like just working with the wood panels because I can do all of the processes I enjoy and love on the same surface — I can carve into it, I can paint into the surface, I can collage ... ."

The piece also dovetails with the idea of the matriarch and motherhood, two areas that Hobbs says she has been investigating in her work.

Asked if she and Jacks have ever collaborated on a project, she replies with a laugh, "we collaborated on our children," before adding, "we collaborate in other ways, like how we support each other. He's an amazing artist and I feel so fortunate that I have him as my husband and partner. We balance each other in terms of our strengths and weaknesses. We're able to support each other."

■ ■ ■

Hobbs, the daughter of Angela Hobbs Williams and Charles R. Williams Sr., remembers enjoying art in kindergarten and elementary school.

"Sometimes my projects would turn out really well and other kids would be like, 'Can you help me with mine?'"

She liked drawing, and took art classes throughout junior high and high school but decided to study biology when she enrolled at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

"Growing up I sang in the choir, I danced, I did art but I just didn't really have examples of those being a career path," she says. "I thought, well, I'll be a biology major and go to medical school."

She eventually realized that biology wasn't the best path and began enrolling in art and dance classes to do something fun. After transferring to the University of Arkansas Little Rock, where she met Jacks, the pull of art became too strong to ignore.

"Art seemed like the best thing for me, and I started making changes," she says.

One of her professors was Aj Smith, who first met Hobbs when she modeled for his drawing classes.

"She exhibited an interest in the arts," remembers Smith, who retired in 2018. "We would talk, and she professed her interest in becoming an art major and I encouraged her to consider it."

Hobbs earned a bachelor's degree in painting at UALR, but it was also there that she discovered printmaking.

"Even though I was a painting major we had to take other studio courses, including printmaking," she says. "Honestly, I didn't like it at first."

But then Smith introduced her to Catlett, the sculptor and printmaker whose figurative works depicted the Black experience. It was a revelation for Hobbs.

"Seeing her work, the technical ability and her mastery of it, how familiar her imagery was, I felt like I saw a reflection of myself and my family. It just ticked so many boxes for me.

"I was also at that time when I was really trying to develop my own sense of self as an artist and my own visual language, and deciding what I wanted to say. I was like, I want to make images like these."

A highlight of visiting "The Power of Portraiture" show, she says, was seeing two of Catlett's works — the 1953 linocut "Sharecropper" and "Lovey Twice," a lithograph from 1976.

"I'd only seen ['Lovey Twice'] in textbooks, so having an in-person experience with that work was really special."

Like Catlett, Hobbs' work focuses on Black figures and portraiture.

"I feel like portraiture was always the thing, like the highest achievement ... when you can draw a good portrait you've kind of arrived at this place of being a good artist. I love seeing different types of work from other people, but in terms of what I do, the figure and portraiture have always been central."

Smith is impressed by his former student. He sees Hobbs taking the baton from artists like Betye Saar and "running with it."

"I think she is doing very strong work now. Being a female in the early stages of her career as well as a mother and university professor, that's a tall order. She is very much involved in representing herself as a female artist, trying to communicate a message about female artists, as well as African-American artists, that has been neglected for too long."

This is an installation view of LaToya Hobbs’ works last month at the International Fine Print Dealer’s Association’s Fine Art Print Fair at the Javits Center in New York. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette/Ariston Jacks)

This is an installation view of LaToya Hobbs’ works last month at the International Fine Print Dealer’s Association’s Fine Art Print Fair at the Javits Center in New York. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette/Ariston Jacks)

There's an event from childhood that Hobbs suspects might have had an effect on how she works today.

"In kindergarten, on our supply list was a coloring book. My dad bought me this big coloring book about giraffes, and I liked the fact that mine was so much bigger than everybody else's. I don't know, maybe subconsciously that could be a seed as to why I like to work so large now."

Like, really large. Remember how "Genette's Daughters" is 8 feet by 12 feet? Well her woodcut, "Carving Out Time," reaches mural-like proportions, stretching across five 8-by-12 panels to show a day in the life of Hobbs as an artist and mom and depicts her, Jacks and their sons.

A print of the first panel, "Morning," will be included in "Together," the inaugural exhibit at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Art, which will reopen April 22 after nearly three years of renovations. Hobbs joins Elias Sime, Ryan RedCorn, Oliver Lee Jackson and others in the show.

"She just seemed like a natural fit," says Brian Lang, chief curator and Windgate Foundation curator of contemporary craft at the museum. "The scene of 'Morning' perfectly illustrates the theme of the exhibition, which is loosely organized around three aspects — together with family, together with community, together with nature ... LaToya is an artist who is pushing the limits of printmaking today, and pushing herself as an artist in working on such a large scale. We felt it was important to recognize her for that.""

It's not the first time her work has been shown in the space. She was twice chosen for the annual Delta Exhibition when the museum was known as the Arkansas Arts Center.

"I'm really excited about the newly renovated space," Hobbs says. "I took a tour of the museum on a visit home earlier this year and even in its unfinished state it looked really amazing ... Presenting my work in the inaugural exhibition ... is very special to me because Arkansas is my home state and I'm really excited for my family, friends and museum visitors to see how my practice has evolved."