Blondie is one of those bands that some people dismiss as a few-hits wonder, a trivia answer.

They might be surprised to learn that one of the most anticipated releases of this year is "Against the Odds, 1974-1982," a box set that dives deep into the band's first career (they have had several comebacks, including one in 1999 that occasioned the release of the album "No Exit," which rivals their finest work).

As with a lot of box sets, "Against the Odds" is available in several configurations at several different price points, ranging from a Super Deluxe package that weighs 17 pounds and contains two hardback books to a three-CD version that can be had for about $35.

There's a new graphic novel available from Z2 Comics, also called "Against the Odds," that purports to tell the band's story and illustrates several of their songs. It comes in several versions; the standard one goes for $39.99 ($24.99 softcover), the deluxe for $99.99 and the super deluxe for $499.99.

The gist of the box set is 52 rarities and outtakes, 36 of which have never before been released — including the band's take on the Doors' "Moonlight Drive," a cover version that was so storied and unheard that I simply assumed it was a rumor.

If you geek out on home recordings and half-finished ideas that suggest roads not taken and possibilities foreclosed, diving into this sort of box set is like eating ice cream. Even if the initial excitement eventually settles into something mild and cool, it's still hard to stop.

Blondie is one of the more fascinating American bands, and their five-album run from their 1976 debut to 1980's "Autoamerican" is solid. (1982's "The Hunter," recorded and released only to fulfill a contractual agreement, was unfortunate, though one could argue for their cover of the Marvelettes' 1967 hit "The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game.")

But most people only know the hits — and the image.

Girl singers always have it tough with rock critics, especially male rock critics. There was a time when even Linda Ronstadt was disdained as a pretty warbler. Back in the '70s one writer for a national magazine wrote that Olivia Newton-John had "une voix chucotant mannequinee," which he helpfully translated as "a whispering fashion model's voice." (And what's wrong with that, I'd like to know?)

That same criticism has occasionally been lowered at Deborah Harry, who fronted Blondie. In both cases, it's an inane criticism that dismisses the emotional complexity and latent power of these women's voices. Newton-John was a conversational, rhythm-driven singer when she wanted to be, when it suited the material — she generally kept a lot in reserve. And Harry is one of the more dynamic female vocalists of the rock era, oscillating between a tough-girl snarl and a chilling, zombie-esque bel canto.

It's easy to slot Blondie into a pop music bin; Harry was a Playboy Club hostess from New Jersey and the girlfriend of the band's guitar player Chris Stein, who, it might be assumed, was the real creative engine behind the band. They had some hits, a couple off cover songs, and disappeared for a while until financial considerations forced a comeback. They probably sold most of their records because of the photos on the covers.

BLONDIE IS A GROUP

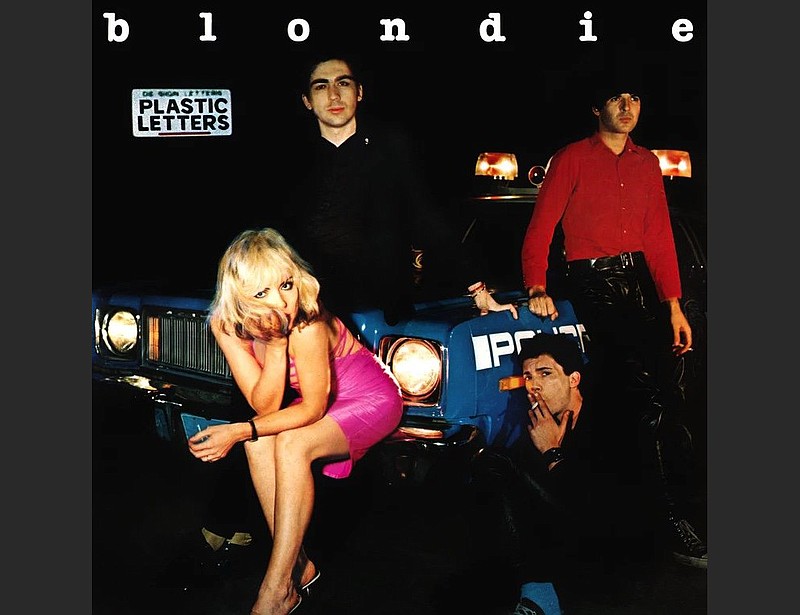

Like a lot of young men, I bought Blondie's second album, "Plastic Letters," in 1978 because of the album cover. It featured members of the band sitting on and around a New York City police car, a 1976 Plymouth Fury to be exact. The focal point, and what captured my interest, was Harry crouched on the car's clunky five-mph bumper in a hot pink mini dress.

I'd rank that cover as among the five most sexist in pop history — Ronstadt's "Hasten Down the Wind" (1976) is another, along with Blondie's "Parallel Lines" (1979) — but the image, shot by Phillip Dixon, who'd become better known for his fashion work, is more evocative than provocative, especially if you consider that in the late '70s, New York City was a grimy and dangerous place.

It was the city of heroin, Serpico and Popeye Doyle; of CBGB (the erstwhile noted music club) and the Mudd Club; the nexus of American punk, new wave and experimental music; performance art; and catwalk exhibitions for emerging fashion designers like Anna Sui and Jasper Conran.

Blondie would emerge as perhaps the most popular band from that '70s New York scene, where the lines between punk and new wave and pop were dithered. Coming out of the same downtown Manhattan scene that spawned the Ramones and Talking Heads, they legitimized disco with their would-be parody song "Heart of Glass," redefined the parameters of European synth-rock with "Call Me," made one of rock's first sorties into hip-hop with "Rapture," and sparked a mini ska revival with "The Tide Is High."

They were fronted by Harry, with a wicked sense of ironic distance and a voice like a crippled angel, but as a lot of the record company ads insisted, Blondie was "a group." While Harry was more than just the girl singer and sex symbol (she wrote, both with guitarist Stein and on her own, and more importantly "conceptualized" and art-directed the band), the band's sound owed much to the effusive drumming of Clem Burke and keyboard player Jimmy Destri's snaky synth lines, which differentiated them from guitar-driven bands like the Ramones.

Before she formed Blondie with Stein in 1974, Harry had been in a band called Elda and the Stilettos, a campy act that parodied the girl groups of the '60s. It was led by Elda Gentile, with Harry and Rosie Ross serving as Supremes to Gentile's Diana Ross. Like Blondie, the Stilettos were a group — they broke up after a record company offered them a contract on the condition that they dump their guitarist (Stein), bassist (Fred Smith — not to be confused with MC5 guitarist and Patti Smith's husband Fred "Sonic" Smith) and drummer (Billy O' Connor).

Before she'd joined the Stilettos, Harry sang backing vocals (and a few leads) for the folk rock outfit Wind in the Willows, waited tables at Max's Kansas City, and worked as a secretary for the BBC's New York offices. Stein was a graduate of the New York School of Design, an art school kid and a photographer of considerable talent. They added Gary Valentine on bass and Burke on drums.

At first they called themselves Angel and the Snake, but construction workers cat-called Harry (who'd dyed her naturally brown hair platinum for her gig with the Stilettos) so often that they decided to lean into the epithet.

But Blondie was a group ....

THE TIDE IS HIGH

.... that broke up in 1982, in classic rock 'n' roll fashion, dissolving in the mist of acrimony.

More than that, Stein contracted a rare genetic disease called pemphigus, that caused him to develop blisters all over his body and inside his mouth and throat. For two years he couldn't swallow solid food; Harry was by his side almost constantly, liquefying his food, dodging tabloid reporters, attempting to preserve their privacy.

She made a handful of solo records during the mid-1980s, including the Nile Rodgers-produced "Koo Koo" and the underrated "Rockbird. " She took a few movie roles (she was very good in David Cronenberg's "Videodrome") and started singing with the Jazz Passengers, which represented a return to her roots.

Stein recovered, or at least became able to manage his illness with steroid treatments. After more than a dozen years together, Stein and Harry broke up. But one of the great rock 'n' roll love stories had a semi-happy ending. They remained friends.

She's godmother to his two daughters.

Blondie’s “Against the Odds”

Blondie’s “Against the Odds”

'LIVE FAST, DIE PRETTY'

Harry has often told the story about how one night, long before Blondie, she was trying to hail a cab in Manhattan in the early morning hours.

"This was back in the early '70s," she told a newspaper in 1989. "I wasn't even in a band then. I was trying to get across town to an after-hours club. A little white car pulls up, and the guy offers me a ride. So I just continued to try and flag a cab down. But he was very persistent, and he asked me where I was going. It was only a couple of blocks away, and he said, 'Well, I'll give you a ride.'

"I got in the car, and it was summertime and the windows were all rolled up except about an inch and a half at the top. So I was sitting there and he wasn't really talking to me. Automatically, I sort of reached to roll down the window and I realized there was no door handle, no window crank, no nothing. The inside of the car was totally stripped."

The car's radio and glove box had also been removed.

Harry managed to force down the window and open the door from the outside. When the driver saw her trying to escape, he turned a corner quickly, and she fell out into Avenue A.

When Ted Bundy was executed in 1989, Harry saw his photograph in the newspaper and immediately thought it must have been Bundy who briefly abducted her. But over the years, she's realized that's highly unlikely — authorities believe Bundy was in Florida at the time, that he never visited New York and he didn't begin his killing spree until 1973.

Harry no longer believes she was once abducted by Ted Bundy. Even so, the legend is likely to persist; that's what legends do.

Blondie had one of the more perfect career arcs ever described by a rock 'n' roll band — five years, six albums, a clutch of hit singles, a lot of impressionable fans who would start bands of their own. It was a moment. It was over quickly.

But like most things, there's a lot more if you care to dig down and look around. "Against the Odds, 1974-1982" offers the chance to do that at a series of price points.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com